Edward S. Curtis

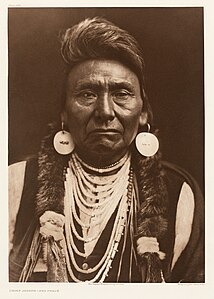

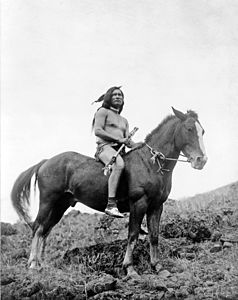

Edward Sheriff Curtis (February 19, 1868 – October 19, 1952, sometimes given as Edward Sherriff Curtis)[1] was an American photographer and ethnologist whose work focused on the American West and on Native American people.[2][3] Sometimes referred to as the "Shadow Catcher", Curtis traveled the United States to document and record the dwindling ways of life of various native tribes through photographs and audio recordings.

For other people named Edward Curtis, see Edward Curtis (disambiguation).

Edward S. Curtis

October 19, 1952 (aged 84)

Photographer, ethnologist

Clara J. Phillips (1874–1932)

Harold Phillips Curtis (1893–1988)

Elizabeth M. Curtis Magnuson (1896–1973)

Florence Curtis Graybill (1899–1987)

Katherine Shirley Curtis Ingram (1909–1982)

Ellen Sherriff (1844–1912)

Johnson Asahel Curtis (1840–87)

Early life[edit]

Curtis was born on February 19, 1868, on a farm near Whitewater, Wisconsin.[4][5] His father, the Reverend Asahel "Johnson" Curtis (1840–1887), was a minister, farmer, and American Civil War veteran[6] born in Ohio. His mother, Ellen Sheriff (1844–1912), was born in Pennsylvania. Curtis's siblings were Raphael (1862 – c. 1885), also called Ray; Edward, called Eddy; Eva (1870–?); and Asahel Curtis (1874–1941).[4] Weakened by his experiences in the Civil War, Johnson Curtis had difficulty in managing his farm, resulting in hardship and poverty for his family.[4]

Around 1874, the family moved from Wisconsin to Minnesota to join Johnson Curtis's father, Asahel Curtis, who ran a grocery store and was a postmaster in Le Sueur County.[4][6] Curtis left school in the sixth grade and soon built his own camera.

Personal life[edit]

Marriage and divorce[edit]

In 1892, Curtis married Clara J. Phillips (1874–1932), who was born in Pennsylvania. Her parents were from Canada. Together they had four children: Harold (1893–1988); Elizabeth M. (Beth) (1896–1973), who married Manford E. Magnuson (1895–1993); Florence (1899–1987), who married Henry Graybill (1893–?); and Katherine Shirley ("Billy") (1909–1982), who married Ray Conger Ingram (1900–1954).

In 1896, the entire family moved to a new house in Seattle. The household then included Curtis's mother, Ellen Sheriff; his sister, Eva Curtis; his brother, Asahel Curtis; Clara's sisters, Susie and Nellie Phillips; and their cousin, William.

During the years of work on The North American Indian, Curtis was often absent from home for most of the year, leaving Clara to manage the children and the studio by herself. After several years of estrangement, Clara filed for divorce on October 16, 1916. In 1919 she was granted the divorce and received Curtis's photographic studio and all of his original camera negatives as her part of the settlement. Curtis and his daughter Beth went to the studio and destroyed all of his original glass negatives, rather than have them become the property of his ex-wife. Clara went on to manage the Curtis studio with her sister Nellie (1880–?), who was married to Martin Lucus (1880–?). Following the divorce, the two oldest daughters, Beth and Florence, remained in Seattle, living in a boarding house separate from their mother. The youngest daughter, Katherine, lived with Clara in Charleston, Kitsap County, Washington.[3]

Death[edit]

On October 19, 1952, at the age of 84, Curtis died of a heart attack in Los Angeles, California, in the home of his daughter Beth. He was buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California. A brief obituary appeared in The New York Times on October 20, 1952:

Collections of Curtis materials[edit]

Northwestern University[edit]

The entire 20 volumes of narrative text and photogravure images for each volume are online.[21][22] Each volume is accompanied by a portfolio of large photogravure plates. The online publishing was supported largely by funds from the Institute for Museum and Library Services.

Library of Congress[edit]

The Prints and Photographs Division Curtis collection consists of more than 2,400 silver-gelatin, first-generation photographic prints – some of which are sepia-toned – made from Curtis's original glass negatives. Most are 5 by 7 inches (13 cm × 18 cm) although nearly 100 are 11 by 14 inches (28 cm × 36 cm) and larger; many include the Curtis file or negative number in the lower left-hand corner of the image.

The Library of Congress acquired these images as copyright deposits from about 1900 through 1930. The dates on them are dates of registration, not the dates when the photographs were taken. About two-thirds (1,608) of these images were not published in The North American Indian and therefore offer a different glimpse into Curtis's work with indigenous cultures. The original glass plate negatives, which had been stored and nearly forgotten in the basement of the Morgan Library, in New York, were dispersed during World War II. Many others were destroyed and some were sold as junk.[7]

Charles Lauriat archive[edit]

Around 1970, David Padwa, of Santa Fe, New Mexico, went to Boston to search for Curtis's original copper plates and photogravures at the Charles E. Lauriat rare bookstore. He discovered almost 285,000 original photogravures as well as all the copper plates and purchased the entire collection which he then shared with Jack Loeffler and Karl Kernberger. They jointly disposed of the surviving Curtis material that was owned by Charles Emelius Lauriat (1874–1937). The collection was later purchased by another group of investors led by Mark Zaplin, of Santa Fe. The Zaplin Group owned the plates until 1982, when they sold them to a California group led by Kenneth Zerbe, the owner of the plates as of 2005. Other glass and nitrate negatives from this set are at the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives in Santa Fe, New Mexico).

Peabody Essex Museum[edit]

Charles Goddard Weld purchased 110 prints that Curtis had made for his 1905–06 exhibit and donated them to the Peabody Essex Museum, where they remain. The 14" by 17" prints are each unique and remain in pristine condition. Clark Worswick, curator of photography for the museum, describes them as:

Legacy[edit]

Revival of interest[edit]

Though Curtis was largely forgotten at the time of his death, interest in his work revived and continues to this day. Casting him as a precursor in visual anthropology, Harald E.L. Prins reviewed his oeuvre in the journal American Anthropologist and noted: "Appealing to his society's infatuation with romantic primitivism, Curtis portrayed American Indians to conform to the cultural archetype of the "vanishing Indian". Elaborated since the 1820s, this ideological construct effectively captured the ambivalent racism of Anglo-American society, which repressed Native spirituality and traditional customs while creating cultural space for the invented Indian of romantic imagination. [Since the 1960s,] Curtis's sepia-toned photographs (in which material evidence of Western civilization has often been erased) had special appeal for this 'Red Power' movement and even helped inspire it."[25]

Major exhibitions of his photographs were presented at the Morgan Library & Museum (1971),[26] the Philadelphia Museum of Art (1972),[27] and the University of California, Irvine (1976).[28] His work was also featured in several anthologies on Native American photography published in the early 1970s.[29] Original printings of The North American Indian began to fetch high prices at auction. In 1972, a complete set sold for $20,000. Five years later, another set was auctioned for $60,500.[30] The revival of interest in Curtis's work can be seen as part of the increased attention to Native American issues during this period.

In 2017 Curtis was inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum.[31]

![Navajo medicine man – Nesjaja Hatali, c. 1907[39]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/42/Navajo_medicine_man.jpg/223px-Navajo_medicine_man.jpg)

![Geronimo – Apache (1905)[40]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/74/Edward_S._Curtis_Geronimo_Apache_cp01002v.jpg/205px-Edward_S._Curtis_Geronimo_Apache_cp01002v.jpg)