Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

Maximilian I (22 March 1459 – 12 January 1519) was King of the Romans from 1486 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1508 until his death in 1519. He was never crowned by the Pope, as the journey to Rome was blocked by the Venetians.[2] He proclaimed himself elected emperor in 1508 (Pope Julius II later recognized this) at Trent,[3][4][5] thus breaking the long tradition of requiring a papal coronation for the adoption of the Imperial title. Maximilian was the only surviving son of Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor, and Eleanor of Portugal. Since his coronation as King of the Romans in 1486, he ran a double government, or Doppelregierung (with a separate court), with his father until Frederick's death in 1493.[6][7]

Maximilian I

4 February 1508 – 12 January 1519

16 February 1486 – 12 January 1519

9 April 1486

Frederick III (1486–1493)

19 August 1493 – 12 January 1519

19 August 1477 – 27 March 1482

22 March 1459

Wiener Neustadt, Inner Austria

12 January 1519 (aged 59)

Wels, Upper Austria

Maximilian expanded the influence of the House of Habsburg through war and his marriage in 1477 to Mary of Burgundy, the ruler of the Burgundian State, heiress of Charles the Bold, though he also lost his family's original lands in today's Switzerland to the Swiss Confederacy. Through the marriage of his son Philip the Handsome to eventual queen Joanna of Castile in 1496, Maximilian helped to establish the Habsburg dynasty in Spain, which allowed his grandson Charles to hold the thrones of both Castile and Aragon.[8] The historian Thomas A. Brady Jr. describes him as "the first Holy Roman Emperor in 250 years who ruled as well as reigned" and also, the "ablest royal warlord of his generation".[9]

Nicknamed "Coeur d'acier" ("Heart of steel") by Olivier de la Marche and later historians (either as praise for his courage and soldierly qualities or reproach for his ruthlessness as a warlike ruler),[10][11] Maximilian has entered the public consciousness as "the last knight" (der letzte Ritter), especially since the eponymous poem by Anastasius Grün was published (although the nickname likely existed even in Maximilian's lifetime).[12] Scholarly debates still discuss whether he was truly the last knight (either as an idealized medieval ruler leading people on horseback, or a Don Quixote-type dreamer and misadventurer), or the first Renaissance prince—an amoral Machiavellian politician who carried his family "to the European pinnacle of dynastic power" largely on the back of loans.[13][14] Historians of the second half of the nineteenth century like Leopold von Ranke tended to criticize Maximilian for putting the interest of his dynasty above that of Germany, hampering the nation's unification process. Ever since Hermann Wiesflecker's Kaiser Maximilian I. Das Reich, Österreich und Europa an der Wende zur Neuzeit (1971–1986) became the standard work, a much more positive image of the emperor has emerged. He is seen as an essentially modern, innovative ruler who carried out important reforms and promoted significant cultural achievements, even if the financial price weighed hard on the Austrians and his military expansion caused the deaths and sufferings of tens of thousands of people.[11][15][16]

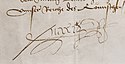

Through an "unprecedented" image-building program, with the help of many notable scholars and artists, in his lifetime, the emperor—"the promoter, coordinator, and prime mover, an artistic impresario and entrepreneur with seemingly limitless energy and enthusiasm and an unfailing eye for detail"—had built for himself "a virtual royal self" of a quality that historians call "unmatched" or "hitherto unimagined".[17][18][19][20][21] To this image, new layers have been added by the works of later artists in the centuries following his death, both as continuation of deliberately crafted images developed by his program as well as development of spontaneous sources and exploration of actual historical events, creating what Elaine Tennant dubs the "Maximilian industry".[20][22]

Tu felix Austria nube[edit]

Background[edit]

Traditionally, German dynasties had exploited the potential of the imperial title to bring Eastern Europe into the fold, in addition to their lands north and south of the Alps. Under Sigismund, the predecessors of the Habsburgs, the Luxemburgs, had managed to gain an empire almost comparable in scale to the later Habsburg empire, although at the same time they lost the Kingdom of Burgundy and control over Italian territories. Their focus on the East, especially Hungary (which was outside the Holy Roman Empire and also gained by the Luxemburgs with a marriage), allowed the new Burgundian rulers from the House of Valois to foster discontent among German princes. Thus, the Habsburgs were forced to refocus their attention on the West. Frederick III's cousin and predecessor, Albert II (who was Sigismund's son-in-law and heir through his marriage with Elizabeth of Luxembourg) had managed to combine the crowns of Germany, Hungary, Bohemia and Croatia under his rule, but he died young.[232][233][234] During his rule, Maximilian had a double focus on both the East and the West. The successful expansion (with the notable role of marriage policy) under Maximilian bolstered his position in the Empire, and also created more pressure for an imperial reform, so that they could get more resources and coordinated help from the German territories to defend their realms and counter hostile powers such as France.[235][236]

Maximilian was married three times, but only the first marriage produced offspring:

The marriage produced three children, of whom only two survived:

The drive behind this marriage, to the great annoyance of Frederick III (who characterized it as "disgraceful"), was the desire of personal revenge against the French (Maximilian blamed France for the great tragedies of his life up to and including Mary of Burgundy's death, political upheavals that followed, troubles in the relationship with his son and later, Philip's death[757][758]). The young King of the Romans had in mind a pincer grip against the Kingdom of France, while Frederick wanted him to focus on expansion towards the East and maintenance of stability in newly reacquired Austria.[6][7] But Brittany was so weak that it could not resist French advance by itself even briefly like the Burgundian State had done, while Maximilian could not even personally come to Brittany to consummate the marriage.[48]

In addition, he had several illegitimate children, but the number and identities of those are a matter of great debate. Johann Jakob Fugger writes in Ehrenspiegel (Mirror of Honour) that the emperor began fathering illegitimate children after becoming a widower, and there were eight children in total, four boys and four girls.[764]

Triumphal woodcuts[edit]

A set of woodcuts called the Triumph of Emperor Maximilian I. See also Category:Triumphal Procession of Maximilian I – Wikimedia Commons