Hungarian prehistory

Hungarian prehistory (Hungarian: magyar őstörténet) spans the period of history of the Hungarian people, or Magyars, which started with the separation of the Hungarian language from other Finno-Ugric or Ugric languages around 800 BC, and ended with the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin around 895 AD. Based on the earliest records of the Magyars in Byzantine, Western European, and Hungarian chronicles, scholars considered them for centuries to have been the descendants of the ancient Scythians and Huns. This historiographical tradition disappeared from mainstream history after the realization of similarities between the Hungarian language and the Uralic languages in the late 18th century. Thereafter, linguistics became the principal source of the study of the Hungarians' ethnogenesis. In addition, chronicles written between the 9th and 15th centuries, the results of archaeological research and folklore analogies provide information on the Magyars' early history.

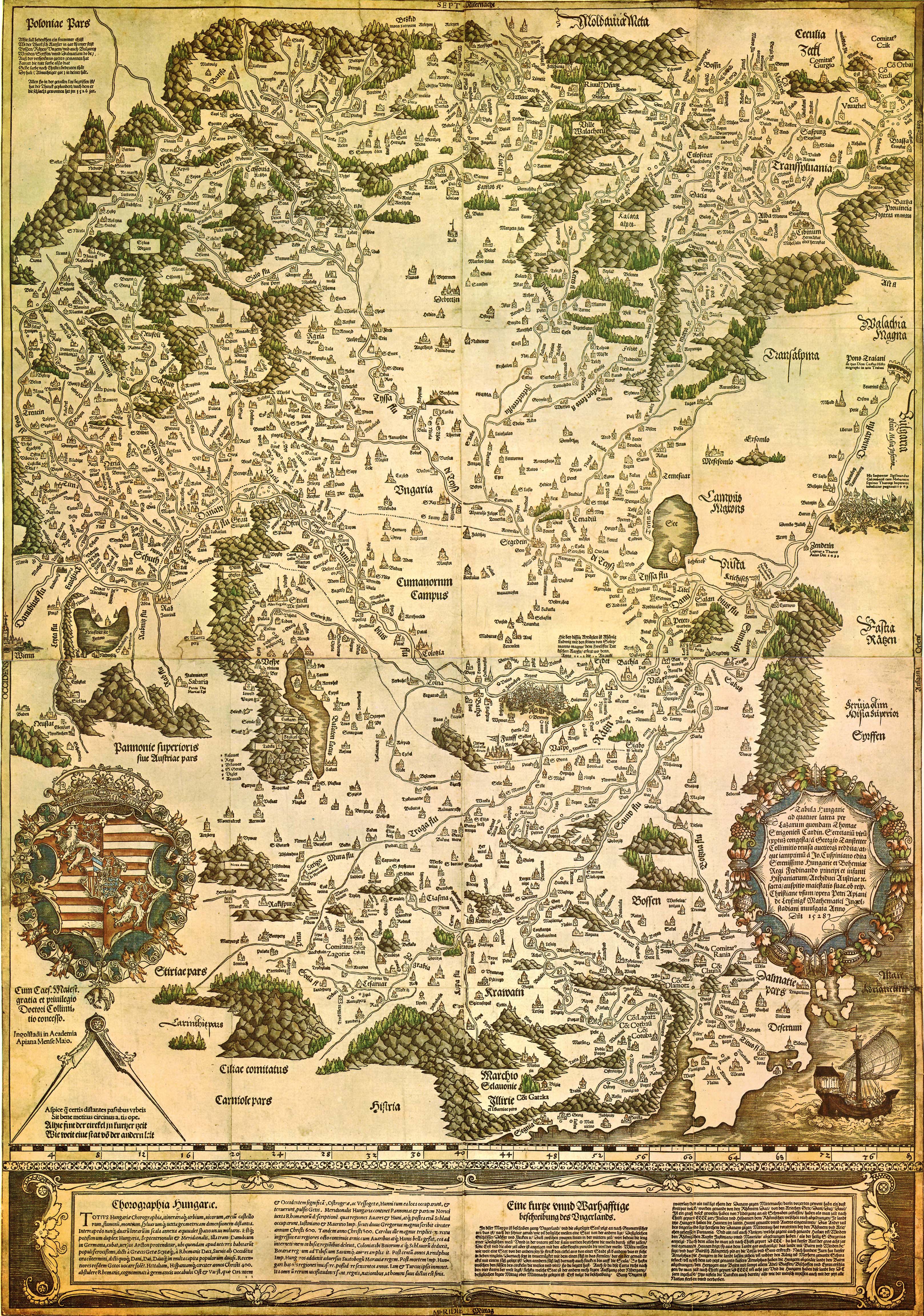

For the pre-conquest history and prehistory of Hungary, see History of Hungary before the Hungarian Conquest.

Study of pollen in fossils based on cognate words for certain trees – including larch and elm – in the daughter languages suggests the speakers of the Proto-Uralic language lived in the wider region of the Ural Mountains, which were inhabited by scattered groups of Neolithic hunter-gatherers in the 4th millennium BC. They spread over vast territories, which caused the development of a separate Proto-Finno-Ugric language by the end of the millennium. Linguistic studies and archaeological research evidence that those who spoke this language lived in pit-houses and used decorated clay vessels. The expansion of marshlands after around 2600 BC caused new migrations. No scholarly consensus on the Urheimat, or original homeland, of the Ugric peoples exists: they lived either in the region of the Tobol River or along the Kama River and the upper courses of the Volga River around 2000 BC. They lived in settled communities, cultivated millet, wheat, and other crops, and bred animals – especially horses, cattle, and pigs. Loan words connected to animal husbandry from Proto-Iranian show that they had close contacts with their neighbors. The southernmost Ugric groups adopted a nomadic way of life by around 1000 BC, because of the northward expansion of the steppes.

The development of the Hungarian language started around 800 BC with the withdrawal of the grasslands and the parallel southward migration of the nomadic Ugric groups. The history of the ancient Magyars during the next thousand years is uncertain; they lived in the steppes but the location of their Urheimat is subject to scholarly debates. According to one theory, they initially lived east of the Urals and migrated west to "Magna Hungaria" by 600 AD at the latest. Other scholars say Magna Hungaria was the Magyars' original homeland, from where they moved either to the region of the Don River or towards the Kuban River before the 830s AD. Hundreds of loan words adopted from Oghuric Turkic languages prove the Magyars were closely connected to Turkic peoples. Byzantine and Muslim authors regarded them as a Turkic people in the 9th and 10th centuries.

An alliance between the Magyars and the Bulgarians in the late 830s was the first historical event that was recorded with certainty in connection with the Magyars. According to the Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, the Magyars lived in Levedia in the vicinity of the Khazar Khaganate in the early 9th century and supported the Khazars in their wars "for three years". The Magyars were organized into tribes, each headed by their own "voivodes", or military leaders. After a Pecheneg invasion against Levedia, a group of Magyars crossed the Caucasus Mountains and settled in the lands south of the mountains, but the majority of the people fled to the steppes north of the Black Sea. From their new homeland, which was known as Etelköz, the Magyars controlled the lands between the Lower Danube and the Don River in the 870s. The confederation of their seven tribes was led by two supreme chiefs, the kende and the gyula. The Kabars – a group of rebellious subjects of the Khazar turks – joined the Magyars in Etelköz. The Magyars regularly invaded the neighboring Slavic tribes, forcing them to pay a tribute and seizing prisoners to be sold to the Byzantines. Taking advantage of the wars between Bulgaria, East Francia, and Moravia, they invaded Central Europe at least four times between 861 and 894. A new Pecheneg invasion compelled the Magyars to leave Etelköz, cross the Carpathian Mountains, and settle in the Carpathian Basin around 895.