Formant

In speech science and phonetics, a formant is the broad spectral maximum that results from an acoustic resonance of the human vocal tract.[1][2] In acoustics, a formant is usually defined as a broad peak, or local maximum, in the spectrum.[3][4] For harmonic sounds, with this definition, the formant frequency is sometimes taken as that of the harmonic that is most augmented by a resonance. The difference between these two definitions resides in whether "formants" characterise the production mechanisms of a sound or the produced sound itself. In practice, the frequency of a spectral peak differs slightly from the associated resonance frequency, except when, by luck, harmonics are aligned with the resonance frequency, or when the sound source is mostly non-harmonic, as in whispering and vocal fry.

A room can be said to have formants characteristic of that particular room, due to its resonances, i.e., to the way sound reflects from its walls and objects. Room formants of this nature reinforce themselves by emphasizing specific frequencies and absorbing others, as exploited, for example, by Alvin Lucier in his piece I Am Sitting in a Room. In acoustic digital signal processing, the way a collection of formants (such as a room) affects a signal can be represented by an impulse response.

In both speech and rooms, formants are characteristic features of the resonances of the space. They are said to be excited by acoustic sources such as the voice, and they shape (filter) the sources' sounds, but they are not sources themselves.

History[edit]

From an acoustic point of view, phonetics had a serious problem with the idea that the effective length of vocal tract changed vowels.[5] Indeed, when the length of the vocal tract changes, all the acoustic resonators formed by mouth cavities are scaled, and so are their resonance frequencies. Therefore, it was unclear how vowels could depend on frequencies when talkers with different vocal tract lengths, for instance bass and soprano singers, can produce sounds that are perceived as belonging to the same phonetic category. There had to be some way to normalize the spectral information underpinning the vowel identity. Hermann suggested a solution to this problem in 1894, coining the term “formant”. A vowel, according to him, is a special acoustic phenomenon, depending on the intermittent production of a special partial, or “formant”, or “characteristique” feature. The frequency of the “formant” may vary a little without altering the character of the vowel. For “long e” (ee or iy) for example, the lowest-frequency “formant” may vary from 350 to 440 Hz even in the same person.[6]

Formant estimation[edit]

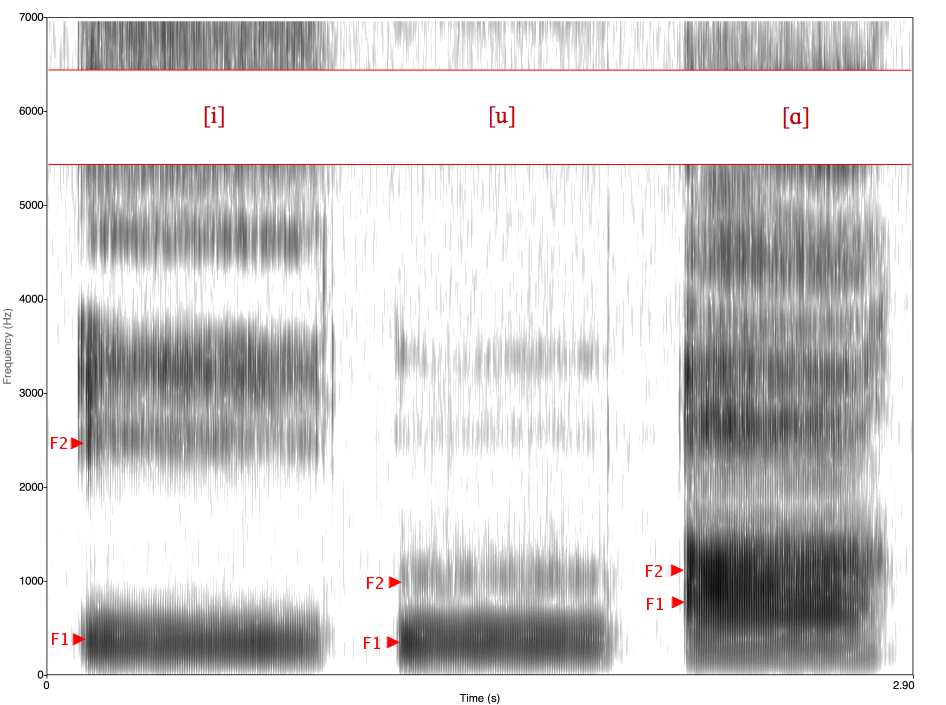

Formants, whether they are seen as acoustic resonances of the vocal tract, or as local maxima in the speech spectrum, like band-pass filters, are defined by their frequency and by their spectral width (bandwidth).

Different methods exist to obtain this information. Formant frequencies, in their acoustic definition, can be estimated from the frequency spectrum of the sound, using a spectrogram (in the figure) or a spectrum analyzer. However, to estimate the acoustic resonances of the vocal tract (i.e. the speech definition of formants) from a speech recording, one can use linear predictive coding. An intermediate approach consists in extracting the spectral envelope by neutralizing the fundamental frequency,[11] and only then looking for local maxima in the spectral envelope.