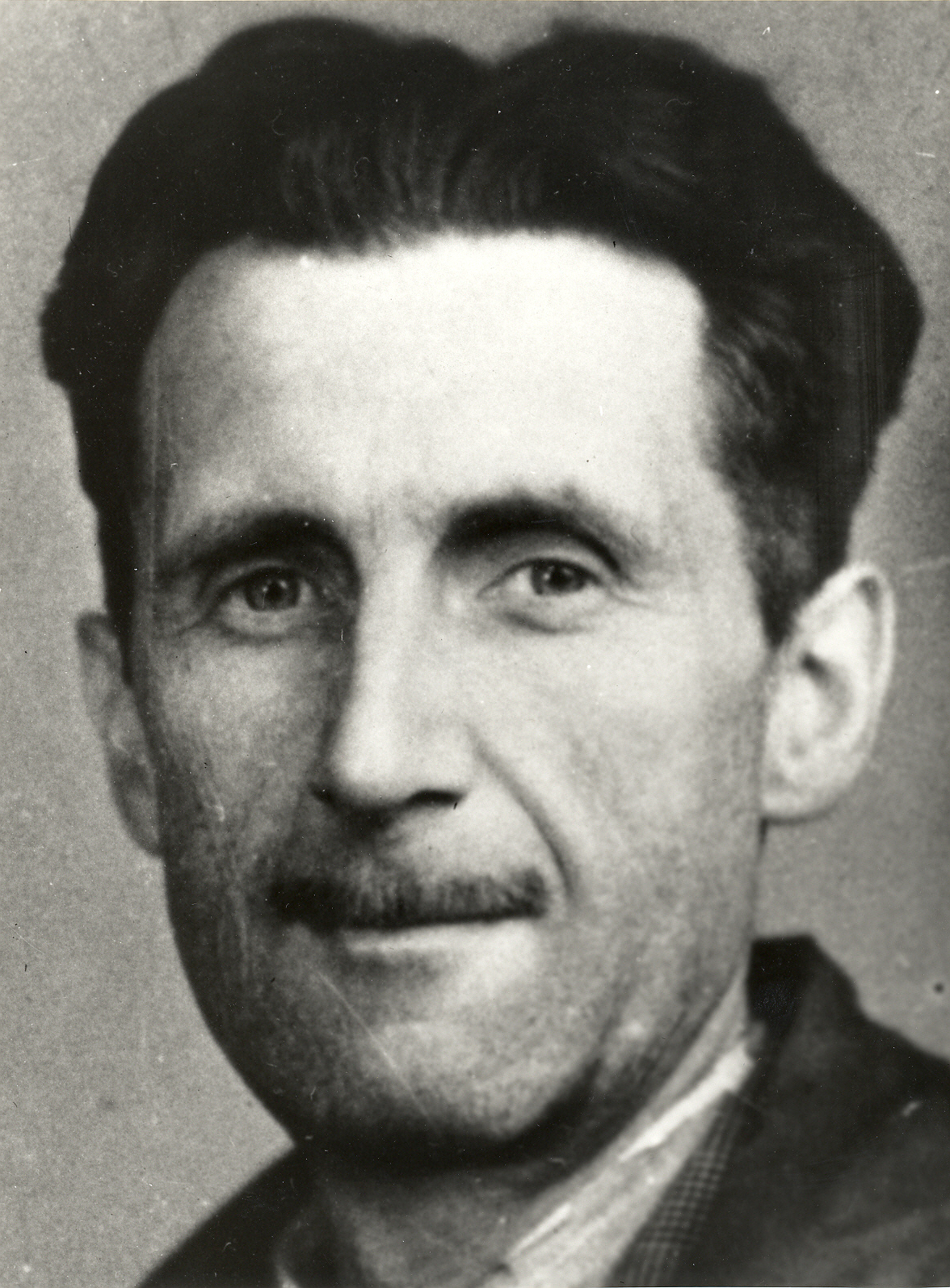

George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950) was an English novelist, poet, essayist, journalist, and critic who wrote under the pen name of George Orwell.[2] His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalitarianism, and support of democratic socialism.[3]

"Orwell" redirects here. For other uses, see Orwell (disambiguation).

George Orwell

21 January 1950 (aged 46)

All Saints' Church, Sutton Courtenay, Oxfordshire, England

- Novelist

- essayist

- journalist

- literary critic

Independent Labour (from 1938)

George Orwell

English

1928–1949[1]

- Down and Out in Paris and London (1933)

- The Road to Wigan Pier (1937)

- Homage to Catalonia (1938)

- Animal Farm (1945)

- Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949)

Orwell produced literary criticism, poetry, fiction, and polemical journalism. He is known for the allegorical novella Animal Farm (1945) and the dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949). His non-fiction works, including The Road to Wigan Pier (1937), documenting his experience of working-class life in the industrial north of England, and Homage to Catalonia (1938), an account of his experiences soldiering for the Republican faction of the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), are as critically respected as his essays on politics, literature, language and culture.

Born in India, Blair was raised and educated in England from the age of one. After school he became an Imperial policeman in Burma, before returning to Suffolk, England, where he began his writing career as George Orwell—a name inspired by a favourite location, the River Orwell. He made a living from occasional pieces of journalism, and also worked as a teacher or bookseller while living in London. From the late 1920s to the early 1930s, his success as a writer grew and his first books were published. He was wounded fighting in the Spanish Civil War, leading to his first period of ill health on return to England. During the Second World War he served as a sergeant in the Greenwich Home Guard (1940–41), worked as a journalist and, between 1941 and 1943, worked for the BBC. The 1945 publication of Animal Farm led to fame during his lifetime. During his final years, he worked on Nineteen Eighty-Four and moved between London and the Scottish island of Jura. Nineteen Eighty-Four was published in June 1949, less than a year before his death.

Orwell's work remains influential in popular culture and in political culture, and the adjective "Orwellian"—describing totalitarian and authoritarian social practices—is part of the English language, like many of his neologisms, such as "Big Brother", "Thought Police", "Room 101", "Newspeak", "memory hole", "doublethink", and "thoughtcrime".[4][5] In 2008, The Times named Orwell the second-greatest British writer since 1945.[6]

Personal life[edit]

Childhood[edit]

Jacintha Buddicom's account, Eric & Us, provides an insight into Blair's childhood.[210] She quoted his sister Avril that "he was essentially an aloof, undemonstrative person" and said herself of his friendship with the Buddicoms: "I do not think he needed any other friends beyond the schoolfriend he occasionally and appreciatively referred to as 'CC'". She could not recall him having schoolfriends to stay and exchange visits as her brother Prosper often did in holidays.[211] Cyril Connolly provides an account of Blair as a child in Enemies of Promise.[25] Years later, Blair mordantly recalled his prep school in the essay "Such, Such Were the Joys", claiming among other things that he "was made to study like a dog" to earn a scholarship, which he alleged was solely to enhance the school's prestige with parents. Jacintha Buddicom repudiated Orwell's schoolboy misery described in the essay, stating that "he was a specially happy child". She noted that he did not like his name because it reminded him of a book he greatly disliked—Eric, or, Little by Little, a Victorian boys' school story.[212]

Biographies of Orwell[edit]

Orwell's will requested that no biography of him be written, and his widow, Sonia Brownell, repelled every attempt by those who tried to persuade her to let them write about him. Various recollections and interpretations were published in the 1950s and 1960s, but Sonia saw the 1968 Collected Works[218][319] as the record of his life. She did appoint Malcolm Muggeridge as official biographer, but later biographers have seen this as deliberate spoiling as Muggeridge eventually gave up the work.[320] In 1972, two American authors, Peter Stansky and William Abrahams, produced The Unknown Orwell, an unauthorised account of his early years that lacked any support or contribution from Sonia Brownell.[321]

Sonia Brownell then commissioned Bernard Crick, a professor of politics at the University of London, to complete a biography and asked Orwell's friends to co-operate.[322] Crick collated a considerable amount of material in his work, which was published in 1980,[322] but his questioning of the factual accuracy of Orwell's first-person writings led to conflict with Brownell, and she tried to suppress the book. Crick concentrated on the facts of Orwell's life rather than his character, and presented primarily a political perspective on Orwell's life and work.[323]

After Sonia Brownell's death, other works on Orwell were published in the 1980s, particularly in 1984. These included collections of reminiscences by Audrey Coppard and Crick[217][319] and Stephen Wadhams.[24][324]

In 1991, Michael Shelden, an American professor of literature, published a biography.[32][325] More concerned with the literary nature of Orwell's work, he sought explanations for Orwell's character and treated his first-person writings as autobiographical. Shelden introduced new information that sought to build on Crick's work.[322] Shelden speculated that Orwell possessed an obsessive belief in his failure and inadequacy.[326]

Peter Davison's publication of the Complete Works of George Orwell, completed in 2000,[327][328] made most of the Orwell Archive accessible to the public. Jeffrey Meyers, a prolific American biographer, was first to take advantage of this and published a book in 2001 that investigated the darker side of Orwell and questioned his saintly image.[322] Why Orwell Matters (released in the United Kingdom as Orwell's Victory) was published by Christopher Hitchens in 2002.[329]

In 2003, the centenary of Orwell's birth resulted in biographies by Gordon Bowker[330] and D. J. Taylor,[331] both academics and writers in the United Kingdom. Taylor notes the stage management which surrounds much of Orwell's behaviour[11] and Bowker highlights the essential sense of decency which he considers to have been Orwell's main motivation.[332] An updated edition of Taylor's biography has been published in 2023 entitled Orwell: The New Life, published by Constable.[333][334]

In 2018, Ronald Binns published the first detailed study of Orwell's years in Suffolk, Orwell in Southwold. In 2020, Professor Richard Bradford wrote a new biography, entitled Orwell: A Man of Our Time[335] while in 2021 Rebecca Solnit reflected on what gardening may have meant to Orwell and what it means to gardeners everywhere, in her book Orwell's Roses.[336]

Two books about Orwell's relationship with his first wife, Eileen O'Shaughnessy, and her role in his life and career, have been published: Eileen: The Making of George Orwell by Sylvia Topp (2020)[337] and Wifedom: Mrs Orwell's Invisible Life by Anna Funder (2023).[338][331] In her book Funder claims that Orwell was misogynistic and sadistic. This sparked a strong controversy among Orwell's biographers, particularly with Topp. Celia Kirwan's family also intervened in the discussion, believing that the attribution to their relative of a relationship with Orwell, as stated by Funder, is false. The publishing house of Wifedom was forced to remove that reference from the book.[339]

According to Blake Morrison, after D. J. Taylor's 2023 Orwell: The New Life "No further biography will be needed for the foreseeable future, though it seems that one or even two of Orwell's journals are lying in a Moscow archive."[340]

Works:

Catalogs and collections: