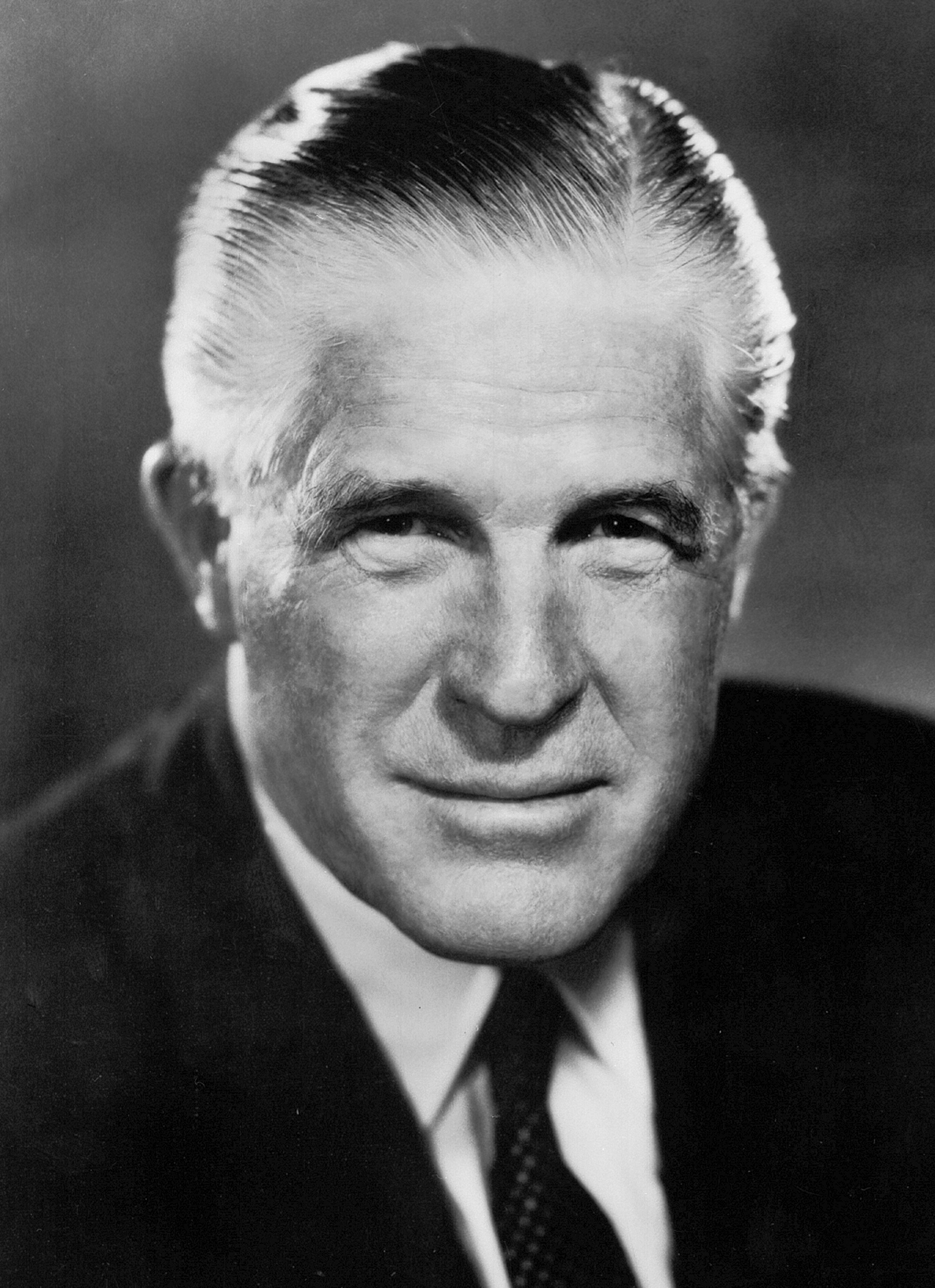

George W. Romney

George Wilcken Romney (July 8, 1907 – July 26, 1995) was an American businessman and politician. A member of the Republican Party, he served as chairman and president of American Motors Corporation from 1954 to 1962, the 43rd governor of Michigan from 1963 to 1969, and 3rd secretary of Housing and Urban Development from 1969 to 1973. He was the father of Mitt Romney, who was a governor of Massachusetts and the 2012 Republican presidential nominee and currently serves as the United States senator from Utah; the husband of 1970 U.S. Senate candidate Lenore Romney; and the paternal grandfather of former Republican National Committee chair Ronna McDaniel.

For other people with the same name, see George Romney (disambiguation).

George W. Romney

T. John Lesinski

William Milliken

July 26, 1995 (aged 88)

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, U.S.

Republican (1959–1995)

4, including Mitt

Romney was born to American parents living in the Mormon colonies in Mexico; events during the Mexican Revolution forced his family to flee back to the United States when he was a child. The family lived in several states and ended up in Salt Lake City, Utah, where they struggled during the Great Depression. Romney worked in a number of jobs, served as a Mormon missionary in the United Kingdom, and attended several colleges in the U.S. but did not graduate from any of them. In 1939, he moved to Detroit and joined the American Automobile Manufacturers Association, where he served as the chief spokesman for the automobile industry during World War II and headed a cooperative arrangement in which companies could share production improvements. He joined Nash-Kelvinator Corporation in 1948, and became the chief executive of its successor, American Motors, in 1954. There he turned around the struggling firm by focusing all efforts on the compact Rambler car. Romney mocked the products of the "Big Three" automakers as "gas-guzzling dinosaurs" and became one of the first high-profile, media-savvy business executives. Devoutly religious, he presided over the Detroit stake of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Having entered politics in 1961 by participating in a state constitutional convention to rewrite the Michigan Constitution, Romney was elected Governor of Michigan in 1962. Re-elected by increasingly large margins in 1964 and 1966, he worked to overhaul the state's financial and revenue structure, greatly expanding the size of state government and introducing Michigan's first state income tax. Romney was a strong supporter of the American Civil Rights Movement. He briefly represented moderate Republicans against conservative Republican Barry Goldwater during the 1964 U.S. presidential election. He requested the intervention of federal troops during the 1967 Detroit riot.

Initially a front runner for the Republican nomination for president of the United States in the 1968 election cycle, he proved an ineffective campaigner and fell behind Richard Nixon in polls. After a mid-1967 remark that his earlier support for the Vietnam War had been due to a "brainwashing" by U.S. military and diplomatic officials in Vietnam, his campaign faltered even more and he withdrew from the contest in early 1968. After being elected president, Nixon appointed Romney as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development. Romney's ambitious plans, which included housing production increases for the poor and open housing to desegregate suburbs, were modestly successful but often thwarted by Nixon. Romney left the administration at the start of Nixon's second term in 1973. Returning to private life, he advocated volunteerism and public service and headed the National Center for Voluntary Action and its successor organizations from 1973 through 1991. He also served as a regional representative of the Twelve within his church.

Missionary work[edit]

After becoming an elder, Romney earned enough money working to fund himself as a Mormon missionary.[39] In October 1926, he sailed to Great Britain and was first assigned to preach in a slum in Glasgow, Scotland.[39] The abject poverty and hopelessness he saw there affected him greatly,[10] but he was ineffective in gaining converts and temporarily suffered a crisis of faith.[40]

In February 1927, he was shifted to Edinburgh and in February 1928 to London,[41] where he kept track of mission finances.[42] He worked under renowned Quorum of the Twelve Apostles intellectuals James E. Talmage and John A. Widtsoe; the latter's admonitions to "Live mightily today, the greatest day of all time is today" made a lasting impression on him.[10][42] Romney experienced British sights and culture and was introduced to members of the peerage and the Oxford Group.[43]

In August 1928, Romney became president of the Scottish missionary district.[43] Operating in a whisky-centric region was difficult, and he developed a new "task force" approach of sending more missionaries to a single location at a time; this successfully drew local press attention and several hundred new recruits.[42][43] Romney's frequent public proselytizing – from Edinburgh's Mound and in London from soap boxes at Speakers' Corner in Hyde Park and from a platform at Trafalgar Square – developed his gifts for debate and sales, which he would use the rest of his career.[29][30][41] Three decades later, Romney said that his missionary time had meant more to him in developing his career than any other experience.[39]

Early career, marriage and children[edit]

Romney returned to the U.S. in late 1928 and studied briefly at the University of Utah and LDS Business College.[44] He followed LaFount to Washington, D.C., in fall 1929, after her father, Harold A. Lafount, had accepted an appointment by President Calvin Coolidge to serve on the Federal Radio Commission.[30][35][44] He worked for Massachusetts Democratic U.S. Senator David I. Walsh during 1929 and 1930, first as a stenographer using speedwriting, then, when his abilities at that proved limited, as a staff aide working on tariffs and other legislative matters.[22][45] Romney researched aspects of the proposed Smoot-Hawley tariff legislation and sat in on committee meetings; the job was a turning point in his career and gave him lifelong confidence in dealing with Congress.[44]

With one of his brothers, Romney opened a dairy bar in nearby Rosslyn, Virginia, during this time. The business soon failed, in the midst of the Great Depression.[30][46] He also attended George Washington University at night.[10][29][45] Based upon a connection he made working for Walsh, Romney was hired as an apprentice for Alcoa in Pittsburgh in June 1930.[46]

When LaFount, an aspiring actress, began earning bit roles in Hollywood movies, Romney arranged to be transferred to Alcoa's Los Angeles office for training as a salesman.[29][46] There he took night classes at the University of Southern California.[47] Romney did not attend for long, or graduate from, any of the colleges in which he was enrolled, accumulating only 2½ years of credits;[48] instead he has been described as an autodidact.[30] LaFount had the opportunity to sign a $50,000, three-year contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios, but Romney convinced her to return to Washington with him[49] as he was assigned a position there with Alcoa as a lobbyist.[46] She later said she had never had a choice of both marriage and an acting career, because the latter would have upstaged him, but expressed no regrets about having chosen the former.[50][51] Romney would later consider wooing her his greatest sales achievement.[49][52]

The couple married on July 2, 1931, at Salt Lake City Temple.[53] They would have four children: Margo Lynn (born 1935), Jane LaFount (born 1938), George Scott (born 1941), and Willard Mitt (born 1947).[54] The couple's marriage reflected aspects of their personalities and courtship. George was devoted to Lenore, and tried to bring her a flower every day, often a single rose with a love note.[55] George was also a strong, blunt personality used to winning arguments by force of will, but the more self-controlled Lenore was unintimidated and willing to push back against him.[55][56] The couple quarreled so much as a result that their grandchildren would later nickname them "the Bickersons" (after the radio comedy sketches), but in the end, their closeness would allow them to settle arguments amicably.[55]

As a lobbyist, Romney frequently competed on behalf of the aluminum industry against the copper industry, and defended Alcoa against charges of being a monopoly.[57][58] He also represented the Aluminum Wares Association.[29][45] In the early 1930s, he helped get aluminum windows installed in the U.S. Department of Commerce Building,[58] at the time the largest office building in the world.[59]

Romney joined the National Press Club and the Burning Tree and Congressional Country Clubs; one reporter watching Romney hurriedly play golf at the last said, "There is a young man who knows where he is going."[60][61] Lenore's cultural refinement and hosting skills, along with her father's social and political connections, helped George in business, and the couple met the Hoovers, the Roosevelts, and other prominent Washington figures.[35][60] He was chosen by Pyke Johnson, a Denver newspaperman and automotive industry trade representative he met at the Press Club, to join the newly formed Trade Association Advisory Committee to the National Recovery Administration.[60] The committee's work continued even after the agency was declared unconstitutional in 1935.[60] During 1937 and 1938, Romney was also president of the Washington Trade Association Executives.[29]

Automotive industry representative[edit]

After nine years with Alcoa, Romney's career had stagnated; there were many layers of executives to climb through and a key promotion he had wanted was given to someone with more seniority.[22][60] Pyke Johnson was vice president of the Automobile Manufacturers Association, which needed a manager for its new Detroit office.[62] Romney got the job and moved there with his wife and two daughters in 1939.[45][62] An association study found Americans using their cars more for short trips and convinced Romney that the trend was towards more functional, basic transportation.[22] In 1942, he was promoted to general manager of the association, a position he held until 1948.[29] Romney also served as president of the Detroit Trade Association in 1941.[29]

In 1940, as World War II raged overseas, Romney helped start the Automotive Committee for Air Defense, which coordinated planning between the automobile and aircraft industries.[63] Immediately following the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor that drew the U.S. into the war, Romney helped turn that committee into, and became managing director of, the Automotive Council for War Production.[63] This organization established a cooperative arrangement in which companies could share machine tools and production improvements, thus maximizing the industry's contribution to the war production effort.[22][64] It embodied Romney's notion of "competitive cooperative capitalism".[64]

With labor leader Victor Reuther, Romney led the Detroit Victory Council, which sought to improve conditions for Detroit workers under wartime stress and deal with the causes of the Detroit race riot of 1943.[65] Romney successfully appealed to the Federal Housing Administration to make housing available to black workers near the Ford Willow Run plant.[66] He also served on the labor-management committee of the Detroit section of the War Manpower Commission.[29]

Romney's influence grew while he positioned himself as chief spokesman of the automobile industry, often testifying before Congressional hearings about production, labor, and management issues;[29] he was mentioned or quoted in over 80 stories in The New York Times during this time.[67] By war's end, 654 manufacturing companies had joined the Automotive Council for War Production, and produced nearly $29 billion in output for the Allied military forces.[68] This included over 3 million motorized vehicles, 80 percent of all tanks and tank parts, 75 percent of all aircraft engines, half of all diesel engines, and a third of all machine guns.[69] Between a fifth and a quarter of all U.S. wartime production was accounted for by the automotive industry.[68][70]

As peacetime production began, Romney persuaded government officials to forgo complex contract-termination procedures, thus freeing auto plants to quickly produce cars for domestic consumption and avoid large layoffs.[22] Romney was director of the American Trade Association Executives in 1944 and 1947, and managing director of the National Automobile Golden Jubilee Committee in 1946.[29] From 1946 to 1949, he represented U.S. employers as a delegate to the Metal Trades Industry conference of the International Labor Office.[71] By 1950, Romney was a member of the Citizens Housing and Planning Council, and criticized racial segregation in Detroit's housing program when speaking before the Detroit City Council.[72] Romney's personality was blunt and intense, giving the impression of a "man in a hurry", and he was considered a rising star in the industry.[35]

American Motors Corporation chief executive[edit]

As managing director of the Automobile Manufacturers Association, Romney became good friends with then-president George W. Mason. When Mason became chairman of the manufacturing firm Nash-Kelvinator in 1948, he invited Romney along "to learn the business from the ground up" as his roving assistant,[73] and the new executive spent a year working in different parts of the company.[74] At a Detroit refrigerator plant of the Kelvinator appliance division, Romney battled the Mechanics Educational Society of America union to institute a new industrial–labor relations program that forestalled the whole facility being shut down.[75] He appealed to the workers by saying, "I am no college man. I've laid floors, I've done lathing. I've thinned beets and shocked wheat."[75] As Mason's protégé, Romney assumed executive assignment for the development of the Rambler.[76]

Mason had long sought a merger of Nash-Kelvinator with one or more other companies, and on May 1, 1954, it merged with Hudson Motor Car to become the American Motors Corporation (AMC).[77] It was the largest merger in the history of the industry, and Romney became an executive vice president of the new firm.[77] In October 1954,[49] Mason suddenly died of acute pancreatitis and pneumonia.[78] Romney was named AMC's president and chairman of the board the same month.[79]

When Romney took over, he canceled Mason's plan to merge AMC with Studebaker-Packard Corporation (or any other automaker).[80] He reorganized upper management, brought in younger executives, and pruned and rebuilt AMC's dealer network.[22] Romney believed that the only way to compete with the "Big Three" (General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler) was to stake the future of AMC on a new smaller-sized car line.[81] Together with chief engineer Meade Moore, by the end of 1957 Romney had completely phased out the Nash and Hudson brands, whose sales had been lagging.[29] The Rambler brand was selected for development and promotion,[82] as AMC pursued an innovative strategy: manufacturing only compact cars. The company struggled badly at first, losing money in 1956, more in 1957, and experiencing defections from its dealer network.[22][81][83] Romney instituted company-wide savings and efficiency measures, and he and other executives reduced their salaries by up to 35 percent.[84] In sticking with his decision to focus on smaller cars, Romney exhibited a stubborness that was common across several generations of Romneys.[85]

Though AMC was on the verge of being taken over by corporate raider Louis Wolfson in 1957, Romney was able to fend him off.[22] Then sales of the Rambler finally took off, leading to unexpected financial success for AMC.[22] It posted its first quarterly profit in three years in 1958, was the only car company to show increased sales during the recession of 1958, and moved from thirteenth to seventh place among worldwide auto manufacturers.[29]

In contrast with the Hudson's NASCAR racing success in the early 1950s,[86] the Ramblers were frequent winners in the coast-to-coast Mobil Economy Run, an annual event on U.S. highways.[87][88][89] Sales remained strong during 1960 and 1961; the Rambler was America's third most popular car both years.[90]

A believer in "competitive cooperative consumerism",[91] Romney was effective in his frequent appearances before Congress.[49] He discussed what he saw as the twin evils of "big labor" and "big business", and called on Congress to break up the Big Three.[30] As the Big Three automakers introduced ever-larger models, AMC undertook a "gas-guzzling dinosaur fighter" strategy,[92] and Romney became the company spokesperson in print advertisements, public appearances, and commercials on the Disneyland television program.[91] Known for his fast-paced, short-sleeved management style that ignored organizational charts and levels of responsibility, he often wrote the ad copy himself.[49]

Romney became what automotive writer Joe Sherman termed "a folk hero of the American auto industry"[93] and one of the first high-profile media-savvy business executives. His focus on small cars as a challenge to AMC's domestic competitors, as well as the foreign-car invasion, was documented in the April 6, 1959, cover story of Time magazine, which concluded that "Romney has brought off singlehanded one of the most remarkable selling jobs in U.S. industry."[22] A full biography of him was published in 1960;[94] the company's resurgence made Romney a household name.[95] The Associated Press named Romney its Man of the Year in Industry for four consecutive years, 1958 through 1961.[96]

The company's stock rose from $7 per share to $90 per share,[30] making Romney a millionaire from stock options.[97] However, whenever he felt his salary and bonus was excessively high for a year, he gave the excess back to the company.[97] After initial wariness, he developed a good relationship with United Automobile Workers leader Walter Reuther,[49] and AMC workers also benefited from a then-novel profit-sharing plan.[98] Romney was one of only a few Michigan corporate chiefs to support passage and implementation of the state Fair Employment Practices Act.[72]

Local church and civic leadership[edit]

Religion was a paramount force in Romney's life.[49][52][99] In a 1959 essay for the Detroit Free Press he said, "My religion is my most precious possession. ... Except for my religion, I easily could have become excessively occupied with industry, social and recreational activities. Sharing personal responsibility for church work with my fellow members has been a vital counterbalance in my life."[100] Following LDS Church practices, he did not drink alcohol or caffeinated beverages, smoke, or swear.[49] His favorite piece of Mormon scripture was from Doctrine and Covenants: "Search diligently, pray always, and be believing, and all things shall work together for your good."[101] Romney and his wife tithed,[102] and from 1955 to 1965, gave 19 percent of their income to the church and another 4 percent to charity.[97]

Romney was a high priest in the Melchizedek priesthood of the LDS,[52] and beginning in 1944 he headed the Detroit church branch[49] (which initially was small enough to meet in a member's house).[103] By the time he was AMC chief, he presided over the Detroit stake,[49] which included not only all of Metro Detroit, Ann Arbor, and the Toledo area of Ohio but also the western edge of Ontario along the Michigan border.[104] In this role, Romney oversaw the religious work of some 2,700 church members, occasionally preached sermons, and supervised the construction of the first stake tabernacle east of the Mississippi River in 100 years.[91][104] Because the stake covered part of Canada, he often interacted with Canadian Mission President Thomas S. Monson.[105] Romney's rise to a leadership role in the church reflected the church's journey from a fringe pioneer religion to one that was closely associated with mainstream American business and values.[35] Due in part to his prominence, the larger Romney family tree would become viewed as "LDS royalty".[103]

Romney and his family lived in affluent Bloomfield Hills,[45] having moved there from Detroit around 1953.[35][106] He became deeply active in Michigan civic affairs.[107] He was on the board of directors of the Children's Hospital of Michigan and the United Foundation of Detroit, and was chairman of the executive committee of the Detroit Round Table of Catholics, Jews, and Protestants.[91] In 1959, he received the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith's Americanism award.[72][108]

Starting in 1956, Romney headed a citizen-based committee for improved educational programs in Detroit's public schools.[92][107] The 1958, final report of the Citizens Advisory Committee on School Needs was largely Romney's work and received considerable public attention; it made nearly 200 recommendations for economy and efficiency, better teacher pay, and new infrastructure funding.[109][110] Romney helped a $90-million education-related bond issue and tax increase win an upset victory in an April 1959 statewide referendum.[109] He organized Citizens for Michigan in 1959, a nonpartisan group that sought to study Detroit's problems and build an informed electorate.[49][111] Citizens for Michigan built on Romney's belief that assorted interest groups held too much influence in government, and that only the cooperation of informed citizens acting for the benefit of all could counter them.[107]

Based on his fame and accomplishments in a state where automobile making was a central topic of conversation, Romney was seen as a natural to enter politics.[107] He first became directly involved in politics in 1959, when he was a key force in the petition drive calling for a constitutional convention to rewrite the Michigan Constitution.[30][98] Romney's sales skills made Citizens for Michigan one of the most effective organizations among those calling for the convention.[107][112] Previously unaffiliated politically, Romney declared himself a member of the Republican Party and gained election to the convention.[107] By early 1960, many in Michigan's somewhat moribund Republican Party were touting Romney as a possible candidate for governor, U.S. senator, or even U.S. vice president.[35][49]

Also in early 1960, Romney served on the Fair Campaign Practices Committee, a group also having Jewish, Catholic, mainline and evangelical Protestant, and Orthodox Christian members. It issued a report whose guiding principles were that no candidate for elected office should be supported or opposed due to their religion and that no campaign for office should be seen as an opportunity to vote for one religion against another. This statement helped pave the way for John F. Kennedy's famous speech on religion and public office later that year.[113] Romney briefly considered a run in the 1960 Senate election,[49] but instead became a vice president of the constitutional convention that revised the Michigan constitution during 1961 and 1962.[114][115]