Germ theory of disease

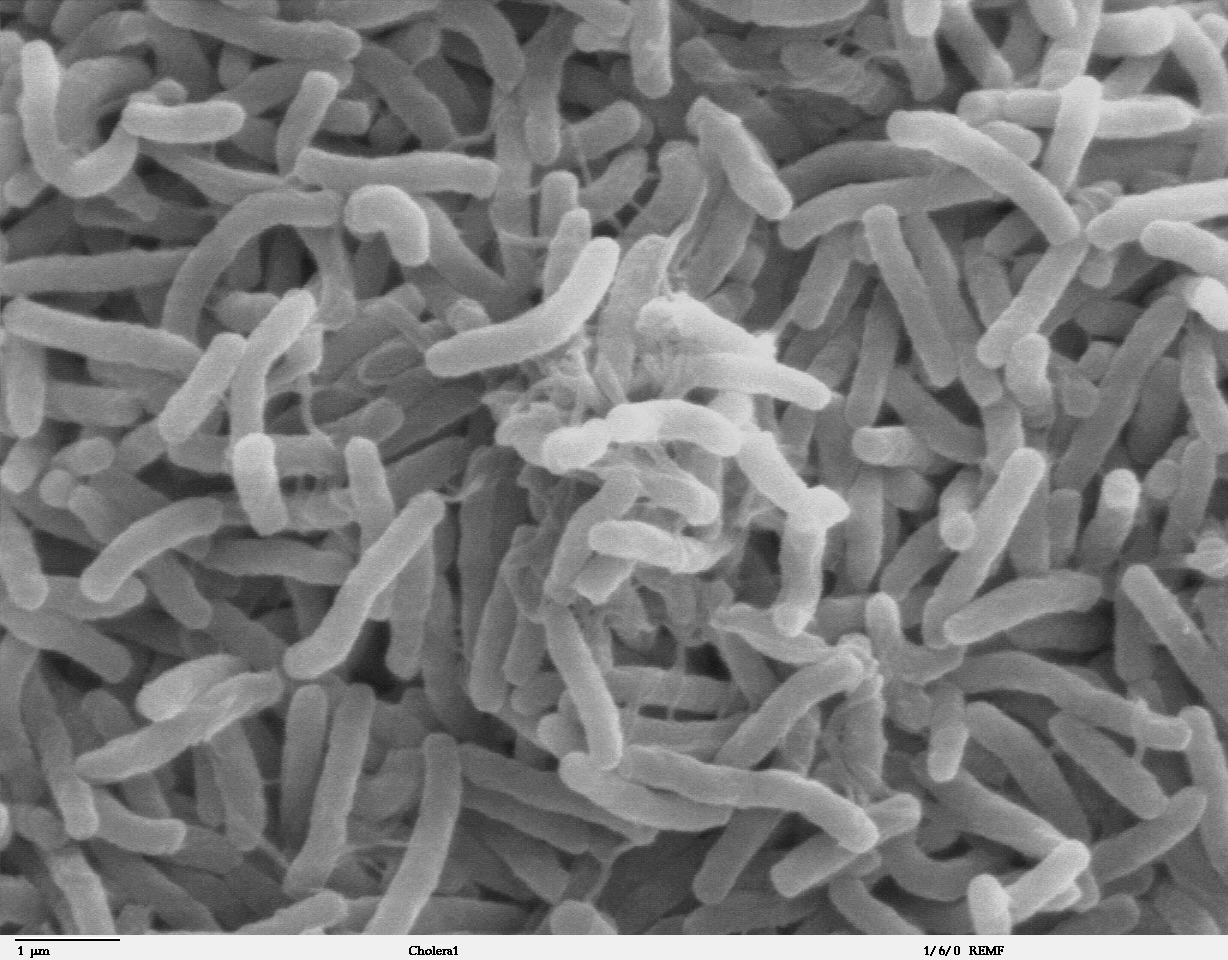

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted scientific theory for many diseases. It states that microorganisms known as pathogens or "germs" can cause disease. These small organisms, too small to be seen without magnification, invade humans, other animals, and other living hosts. Their growth and reproduction within their hosts can cause disease. "Germ" refers to not just a bacterium but to any type of microorganism, such as protists or fungi, or other pathogens that can cause disease, such as viruses, prions, or viroids.[1] Diseases caused by pathogens are called infectious diseases. Even when a pathogen is the principal cause of a disease, environmental and hereditary factors often influence the severity of the disease, and whether a potential host individual becomes infected when exposed to the pathogen. Pathogens are disease-carrying agents that can pass from one individual to another, both in humans and animals. Infectious diseases are caused by biological agents such as pathogenic microorganisms (viruses, bacteria, and fungi) as well as parasites.

Basic forms of germ theory were proposed by Girolamo Fracastoro in 1546, and expanded upon by Marcus von Plenciz in 1762. However, such views were held in disdain in Europe, where Galen's miasma theory remained dominant among scientists and doctors.

By the early 19th century, smallpox vaccination was commonplace in Europe, though doctors were unaware of how it worked or how to extend the principle to other diseases. A transitional period began in the late 1850s with the work of Louis Pasteur. This work was later extended by Robert Koch in the 1880s. By the end of that decade, the miasma theory was struggling to compete with the germ theory of disease. Viruses were initially discovered in the 1890s. Eventually, a "golden era" of bacteriology ensued, during which the germ theory quickly led to the identification of the actual organisms that cause many diseases.[2]

Development of germ theory[edit]

Greece and Rome[edit]

In Antiquity, the Greek historian Thucydides (c. 460 – c. 400 BC) was the first person to write, in his account of the plague of Athens, that diseases could spread from an infected person to others.[5][6]

One theory of the spread of contagious diseases that were not spread by direct contact was that they were spread by spore-like "seeds" (Latin: semina) that were present in and dispersible through the air. In his poem, De rerum natura (On the Nature of Things, c. 56 BC), the Roman poet Lucretius (c. 99 BC – c. 55 BC) stated that the world contained various "seeds", some of which could sicken a person if they were inhaled or ingested.[7][8]

The Roman statesman Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 BC) wrote, in his Rerum rusticarum libri III (Three Books on Agriculture, 36 BC): "Precautions must also be taken in the neighborhood of swamps... because there are bred certain minute creatures which cannot be seen by the eyes, which float in the air and enter the body through the mouth and nose and there cause serious diseases."[9]

The Greek physician Galen (AD 129 – c. 200/216) speculated in his On Initial Causes (c. 175 AD that some patients might have "seeds of fever".[7]: 4 In his On the Different Types of Fever (c. 175 AD), Galen speculated that plagues were spread by "certain seeds of plague", which were present in the air.[7]: 6 And in his Epidemics (c. 176–178 AD), Galen explained that patients might relapse during recovery from fever because some "seed of the disease" lurked in their bodies, which would cause a recurrence of the disease if the patients did not follow a physician's therapeutic regimen.[7]: 7

The Middle Ages[edit]

A basic form of contagion theory dates back to medicine in the medieval Islamic world, where it was proposed by Persian physician Ibn Sina (known as Avicenna in Europe) in The Canon of Medicine (1025), which later became the most authoritative medical textbook in Europe up until the 16th century. In Book IV of the El-Kanun, Ibn Sina discussed epidemics, outlining the classical miasma theory and attempting to blend it with his own early contagion theory. He mentioned that people can transmit disease to others by breath, noted contagion with tuberculosis, and discussed the transmission of disease through water and dirt.[10]

The concept of invisible contagion was later discussed by several Islamic scholars in the Ayyubid Sultanate who referred to them as najasat ("impure substances"). The fiqh scholar Ibn al-Haj al-Abdari (c. 1250–1336), while discussing Islamic diet and hygiene, gave warnings about how contagion can contaminate water, food, and garments, and could spread through the water supply, and may have implied contagion to be unseen particles.[11]

During the early Middle Ages, Isidore of Seville (c. 560–636) mentioned "plague-bearing seeds" (pestifera semina) in his On the Nature of Things (c. AD 613).[7]: 20 Later in 1345, Tommaso del Garbo (c. 1305–1370) of Bologna, Italy mentioned Galen's "seeds of plague" in his work Commentaria non-parum utilia in libros Galeni (Helpful commentaries on the books of Galen).[7]: 214

The 16th century Reformer Martin Luther appears to have had some idea of the contagion theory, commenting 'I have survived three plagues and visited several people who had two plague spots which I touched. But it did not hurt me, thank God. Afterwards when I returned home, I took up Margaret' (born 1534), 'who was then a baby, and put my unwashed hands on her face, because I had forgotten'.[12] In 1546, Italian physician Girolamo Fracastoro published De Contagione et Contagiosis Morbis (On Contagion and Contagious Diseases), a set of three books covering the nature of contagious diseases, categorization of major pathogens, and theories on preventing and treating these conditions. Fracastoro blamed "seeds of disease" that propagate through direct contact with an infected host, indirect contact with fomites, or through particles in the air.[13]

The Early Modern Period[edit]

In 1668, Italian physician Francesco Redi published experimental evidence rejecting spontaneous generation, the theory that living creatures arise from nonliving matter. He observed that maggots only arose from rotting meat that was uncovered. When meat was left in jars covered by gauze, the maggots would instead appear on the gauze's surface, later understood as rotting meat's smell passing through the mesh to attract flies that laid eggs.[14][15]

Microorganisms are said to have been first directly observed in the 1670s by Anton van Leeuwenhoek, an early pioneer in microbiology, considered "the Father of Microbiology". Leeuwenhoek is said to be the first to see and describe bacteria (1674), yeast cells, the teeming life in a drop of water (such as algae), and the circulation of blood corpuscles in capillaries. The word "bacteria" didn't exist yet, so he called these microscopic living organisms "animalcules", meaning "little animals". Those "very little animalcules" he was able to isolate from different sources, such as rainwater, pond and well water, and the human mouth and intestine. Yet German Jesuit priest and scholar Athanasius Kircher may have observed such microorganisms prior to this. One of his books written in 1646 contains a chapter in Latin, which reads in translation "Concerning the wonderful structure of things in nature, investigated by Microscope", stating "who would believe that vinegar and milk abound with an innumerable multitude of worms." Kircher defined the invisible organisms found in decaying bodies, meat, milk, and secretions as "worms." His studies with the microscope led him to the belief, which he was possibly the first to hold, that disease and putrefaction (decay) were caused by the presence of invisible living bodies. In 1646, Kircher (or "Kirchner", as it is often spelled), wrote that "a number of things might be discovered in the blood of fever patients." When Rome was struck by the bubonic plague in 1656, Kircher investigated the blood of plague victims under the microscope. He noted the presence of "little worms" or "animalcules" in the blood and concluded that the disease was caused by microorganisms. He was the first to attribute infectious disease to a microscopic pathogen, inventing the germ theory of disease, which he outlined in his Scrutinium Physico-Medicum (Rome 1658).[16] Kircher's conclusion that disease was caused by microorganisms was correct, although it is likely that what he saw under the microscope were in fact red or white blood cells and not the plague agent itself. Kircher also proposed hygienic measures to prevent the spread of disease, such as isolation, quarantine, burning clothes worn by the infected, and wearing facemasks to prevent the inhalation of germs. It was Kircher who first proposed that living beings enter and exist in the blood.

In 1700, physician Nicolas Andry argued that microorganisms he called "worms" were responsible for smallpox and other diseases.[17]

In 1720, Richard Bradley theorised that the plague and "all pestilential distempers" were caused by "poisonous insects", living creatures viewable only with the help of microscopes.[18]

In 1762, the Austrian physician Marcus Antonius von Plenciz (1705–1786) published a book titled Opera medico-physica. It outlined a theory of contagion stating that specific animalcules in the soil and the air were responsible for causing specific diseases. Von Plenciz noted the distinction between diseases which are both epidemic and contagious (like measles and dysentery), and diseases which are contagious but not epidemic (like rabies and leprosy).[19] The book cites Anton van Leeuwenhoek to show how ubiquitous such animalcules are and was unique for describing the presence of germs in ulcerating wounds. Ultimately, the theory espoused by von Plenciz was not accepted by the scientific community.