Pathogen

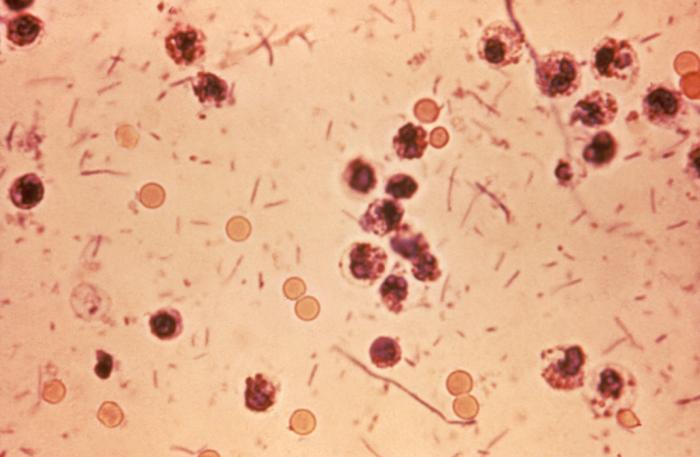

In biology, a pathogen (Greek: πάθος, pathos "suffering", "passion" and -γενής, -genēs "producer of"), in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ.[1]

For other uses, see Pathogen (disambiguation).

The term pathogen came into use in the 1880s.[2][3] Typically, the term pathogen is used to describe an infectious microorganism or agent, such as a virus, bacterium, protozoan, prion, viroid, or fungus.[4][5][6] Small animals, such as helminths and insects, can also cause or transmit disease. However, these animals are usually referred to as parasites rather than pathogens.[7] The scientific study of microscopic organisms, including microscopic pathogenic organisms, is called microbiology, while parasitology refers to the scientific study of parasites and the organisms that host them.

There are several pathways through which pathogens can invade a host. The principal pathways have different episodic time frames, but soil has the longest or most persistent potential for harboring a pathogen.

Diseases in humans that are caused by infectious agents are known as pathogenic diseases. Not all diseases are caused by pathogens, such as black lung from exposure to the pollutant coal dust, genetic disorders like sickle cell disease, and autoimmune diseases like lupus.

Pathogenicity[edit]

Pathogenicity is the potential disease-causing capacity of pathogens, involving a combination of infectivity (pathogen's ability to infect hosts) and virulence (severity of host disease). Koch's postulates are used to establish causal relationships between microbial pathogens and diseases. Whereas meningitis can be caused by a variety of bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic pathogens, cholera is only caused by some strains of Vibrio cholerae. Additionally, some pathogens may only cause disease in hosts with an immunodeficiency. These opportunistic infections often involve hospital-acquired infections among patients already combating another condition.[8]

Infectivity involves pathogen transmission through direct contact with the bodily fluids or airborne droplets of infected hosts, indirect contact involving contaminated areas/items, or transfer by living vectors like mosquitos and ticks. The basic reproduction number of an infection is the expected number of subsequent cases it is likely to cause through transmission.[9]

Virulence involves pathogens extracting host nutrients for their survival, evading host immune systems by producing microbial toxins and causing immunosuppression. Optimal virulence describes a theorized equilibrium between a pathogen spreading to additional hosts to parasitize resources, while lowering their virulence to keep hosts living for vertical transmission to their offspring.[10]

Pathogen hosts[edit]

Bacteria[edit]

While bacteria are typically viewed as pathogens, they serve as hosts to bacteriophage viruses (commonly known as phages). The bacteriophage life cycle involves the viruses injecting their genome into bacterial cells, inserting those genes into the bacterial genome, and hijacking the bacteria's machinery to produce hundreds of new phages until the cell bursts open to release them for additional infections. Typically, bacteriophages are only capable of infecting a specific species or strain.[33]

Streptococcus pyogenes uses a Cas9 nuclease to cleave foreign DNA matching the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) associated with bacteriophages, removing the viral genes to avoid infection. This mechanism has been modified for artificial CRISPR gene editing.[34]

Plants[edit]

Plants can play host to a wide range of pathogen types, including viruses, bacteria, fungi, nematodes, and even other plants.[35] Notable plant viruses include the papaya ringspot virus, which has caused millions of dollars of damage to farmers in Hawaii and Southeast Asia,[36] and the tobacco mosaic virus which caused scientist Martinus Beijerinck to coin the term "virus" in 1898.[37] Bacterial plant pathogens cause leaf spots, blight, and rot in many plant species.[38] The most common bacterial pathogens for plants are Pseudomonas syringae and Ralstonia solanacearum, which cause leaf browning and other issues in potatoes, tomatoes, and bananas.[38]

Treatment[edit]

Prions[edit]

Despite many attempts, no therapy has been shown to halt the progression of prion diseases.[44]

Viruses[edit]

A variety of prevention and treatment options exist for some viral pathogens. Vaccines are one common and effective preventive measure against a variety of viral pathogens.[45] Vaccines prime the immune system of the host, so that when the potential host encounters the virus in the wild, the immune system can defend against infection quickly. Vaccines designed against viruses include annual influenza vaccines and the two-dose MMR vaccine against measles, mumps, and rubella.[46] Vaccines are not available against the viruses responsible for HIV/AIDS, dengue, and chikungunya.[47]

Treatment of viral infections often involves treating the symptoms of the infection, rather than providing medication to combat the viral pathogen itself.[48][49] Treating the symptoms of a viral infection gives the host immune system time to develop antibodies against the viral pathogen. However, for HIV, highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is conducted to prevent the viral disease from progressing into AIDS as immune cells are lost.[50]

Sexual interactions[edit]

Many pathogens are capable of sexual interaction. Among pathogenic bacteria, sexual interaction occurs between cells of the same species by the process of genetic transformation. Transformation involves the transfer of DNA from a donor cell to a recipient cell and the integration of the donor DNA into the recipient genome through genetic recombination. The bacterial pathogens Helicobacter pylori, Haemophilus influenzae, Legionella pneumophila, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Streptococcus pneumoniae frequently undergo transformation to modify their genome for additional traits and evasion of host immune cells.[59]

Eukaryotic pathogens are often capable of sexual interaction by a process involving meiosis and fertilization. Meiosis involves the intimate pairing of homologous chromosomes and recombination between them. Examples of eukaryotic pathogens capable of sex include the protozoan parasites Plasmodium falciparum, Toxoplasma gondii, Trypanosoma brucei, Giardia intestinalis, and the fungi Aspergillus fumigatus, Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans.[59]

Viruses may also undergo sexual interaction when two or more viral genomes enter the same host cell. This process involves pairing of homologous genomes and recombination between them by a process referred to as multiplicity reactivation. The herpes simplex virus, human immunodeficiency virus, and vaccinia virus undergo this form of sexual interaction.[59]

These processes of sexual recombination between homologous genomes supports repairs to genetic damage caused by environmental stressors and host immune systems.[60]