Gregorian calendar

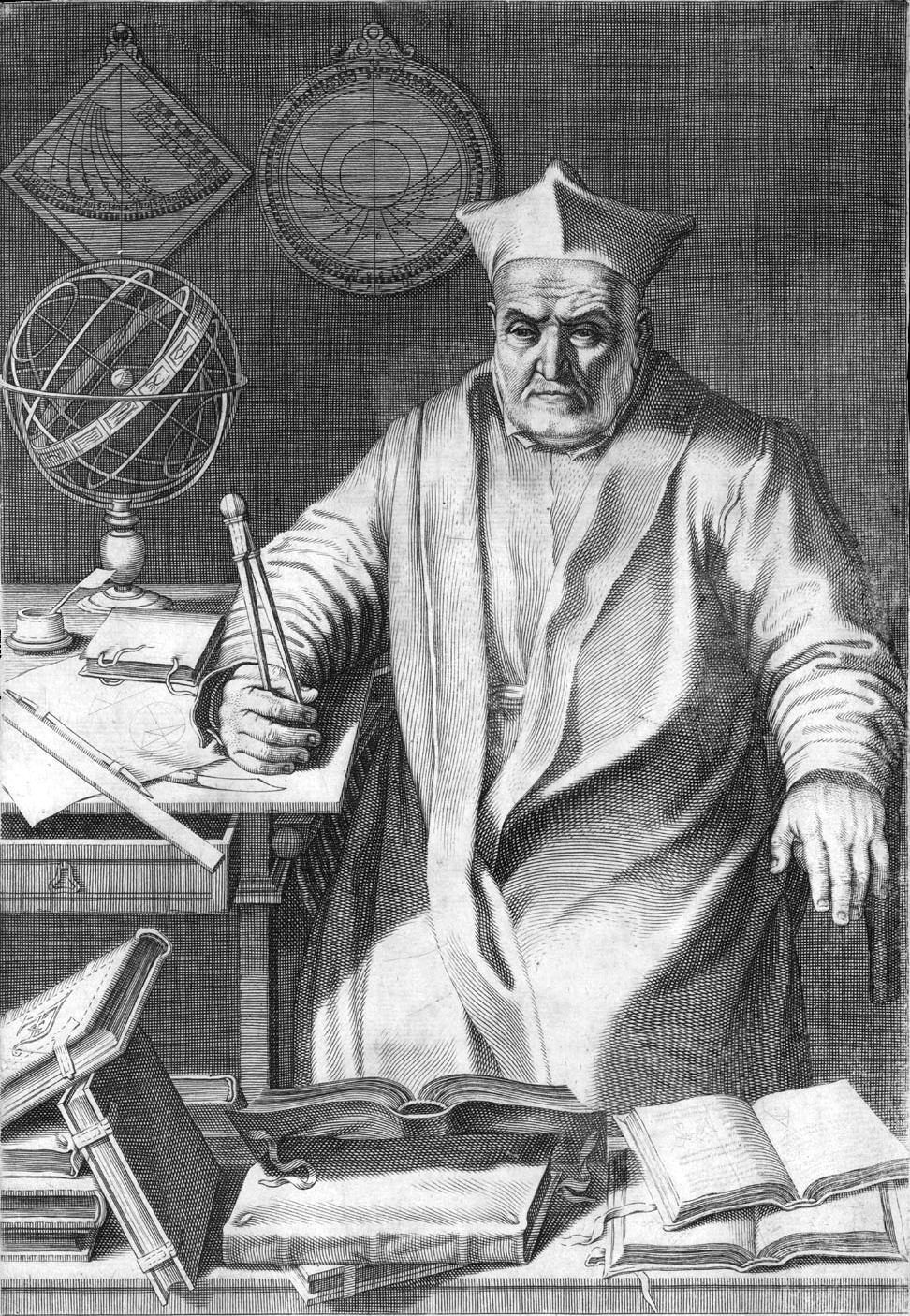

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world.[1][a] It went into effect in October 1582 following the papal bull Inter gravissimas issued by Pope Gregory XIII, which introduced it as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian calendar. The principal change was to space leap years differently so as to make the average calendar year 365.2425 days long, more closely approximating the 365.2422-day 'tropical' or 'solar' year that is determined by the Earth's revolution around the Sun.

For the calendar of religious holidays and periods, see Liturgical year. For this year's Gregorian calendar, see Leap year starting on Monday.

The rule for leap years is:

There were two reasons to establish the Gregorian calendar. First, the Julian calendar assumed incorrectly that the average solar year is exactly 365.25 days long, an overestimate of a little under one day per century, and thus has a leap year every four years without exception. The Gregorian reform shortened the average (calendar) year by 0.0075 days to stop the drift of the calendar with respect to the equinoxes.[3] Second, in the years since the First Council of Nicaea in AD 325,[b] the excess leap days introduced by the Julian algorithm had caused the calendar to drift such that the March equinox was occurring well before its nominal 21 March date. This date was important to the Christian churches because it is fundamental to the calculation of the date of Easter. To reinstate the association, the reform advanced the date by 10 days:[c] Thursday 4 October 1582 was followed by Friday 15 October 1582.[3] In addition, the reform also altered the lunar cycle used by the Church to calculate the date for Easter, because astronomical new moons were occurring four days before the calculated dates. Whilst the reform introduced minor changes, the calendar continued to be fundamentally based on the same geocentric theory as its predecessor.[4]

The reform was adopted initially by the Catholic countries of Europe and their overseas possessions. Over the next three centuries, the Protestant and Eastern Orthodox countries also gradually moved to what they called the "Improved calendar",[d] with Greece being the last European country to adopt the calendar (for civil use only) in 1923.[5] However, many Orthodox churches continue to use the Julian calendar for religious rites and the dating of major feasts. To unambiguously specify a date during the transition period (in contemporary documents or in history texts), both notations were given, tagged as 'Old Style' or 'New Style' as appropriate. During the 20th century, most non-Western countries also adopted the calendar, at least for civil purposes.

The Gregorian calendar continued to employ the Julian months, which have Latinate names and irregular numbers of days:

Europeans sometimes attempt to remember the number of days in each month by memorizing some form of the traditional verse "Thirty Days Hath September". It appears in Latin,[73] Italian,[74] French[75] and Portuguese,[76] and belongs to a broad oral tradition but the earliest currently attested form of the poem is the English marginalia inserted into a calendar of saints c. 1425:[77][78][79]

Variations appeared in Mother Goose and continue to be taught at schools. The unhelpfulness of such involved mnemonics has been parodied as "Thirty days hath September / But all the rest I can't remember"[80] but it has also been called "probably the only sixteenth-century poem most ordinary citizens know by heart".[81] A common nonverbal alternative is the knuckle mnemonic, considering the knuckles of one's hands as months with 31 days and the lower spaces between them as the months with fewer days. Using two hands, one may start from either pinkie knuckle as January and count across, omitting the space between the index knuckles (July and August). The same procedure can be done using the knuckles of a single hand, returning from the last (July) to the first (August) and continuing through. A similar mnemonic is to move up a piano keyboard in semitones from an F key, taking the white keys as the longer months and the black keys as the shorter ones.

The following are proposed reforms of the Gregorian calendar:

Precursors of the Gregorian reform