HPV vaccine

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines are vaccines that prevent infection by certain types of human papillomavirus (HPV).[19] Available HPV vaccines protect against either two, four, or nine types of HPV.[19][20] All HPV vaccines protect against at least HPV types 16 and 18, which cause the greatest risk of cervical cancer.[19] It is estimated that HPV vaccines may prevent 70% of cervical cancer, 80% of anal cancer, 60% of vaginal cancer, 40% of vulvar cancer, and show more than 90% effectiveness in preventing HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers.[21][22][23][24] They additionally prevent some genital warts, with the quadrivalent and nonavalent vaccines that protect against HPV types HPV-6 and HPV-11 providing greater protection.[19]

Vaccine description

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends HPV vaccines as part of routine vaccinations in all countries, along with other prevention measures.[19] The vaccines require two or three doses depending on a person's age and immune status.[19] Vaccinating girls around the ages of nine to thirteen is typically recommended.[19] The vaccines provide protection for at least 5 to 10 years.[19] Cervical cancer screening is still required following vaccination.[19] Vaccinating a large portion of the population may also benefit the unvaccinated by way of herd immunity.[25]

HPV vaccines are very safe.[19] Pain at the site of injection occurs in about 80% of people.[19] Redness and swelling at the site and fever may also occur.[19] No link to Guillain–Barré syndrome has been found.[19]

The first HPV vaccine became available in 2006.[19][26] As of 2022, 125 countries include HPV vaccine in their routine vaccinations for girls, and 47 countries recommend them for boys, as well.[19] HPV vaccines are on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines[27][28] and prequalified vaccines.[29] Vaccination may be cost effective in low and middle-income countries.[30] As of 2017, Gardasil 9 is the only HPV vaccine available in the United States as it provides protection against more HPV types than the earlier approved vaccines (the original Gardasil and Cervarix).[31][32]

Mechanism of action[edit]

The HPV vaccines are based on hollow virus-like particles (VLPs) assembled from recombinant HPV coat proteins. The natural virus capsid is composed of two proteins, L1 and L2, but vaccines only contain L1.

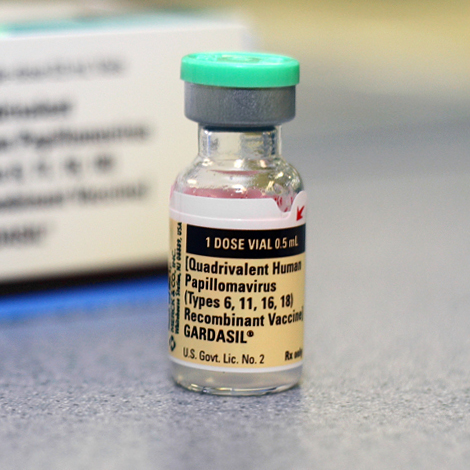

Gardasil contains inactive L1 proteins from four different HPV strains: 6, 11, 16, and 18, synthesized in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Each vaccine dose contains 225 μg of aluminum, 9.56 mg of sodium chloride, 0.78 mg of L-histidine, 50 μg of polysorbate 80, 35 μg of sodium borate, and water. The combination of ingredients totals 0.5 mL.[100]

HPV types 16 and 18 cause about 70% of all cervical cancer.[79] Gardasil also targets HPV types 6 and 11, which together cause about 90 percent of all cases of genital warts.[101]

Gardasil and Cervarix are designed to elicit virus-neutralizing antibody responses that prevent initial infection with the HPV types represented in the vaccine. The vaccines have been shown to offer 100 percent protection against the development of cervical pre-cancers and genital warts caused by the HPV types in the vaccine, with few or no side effects. The protective effects of the vaccine are expected to last a minimum of 4.5 years after the initial vaccination.[42]

While the study period was not long enough for cervical cancer to develop, the prevention of these cervical precancerous lesions (or dysplasias) is believed highly likely to result in the prevention of those cancers.[102]

History[edit]

The vaccine was first developed by the University of Queensland in Australia and the final form was made by researchers at the University of Queensland, Georgetown University Medical Center, University of Rochester, and the U.S. National Cancer Institute.[103] Researchers Ian Frazer and Jian Zhou at the University of Queensland have been accorded priority under U.S. patent law for the invention of the HPV vaccine's basis, the VLPs.[104] In 2006, the FDA approved the first preventive HPV vaccine, marketed by Merck & Co. under the trade name Gardasil. According to a Merck press release,[105] by the second quarter of 2007 it had been approved in 80 countries, many under fast-track or expedited review. Early in 2007, GlaxoSmithKline filed for approval in the United States for a similar preventive HPV vaccine, known as Cervarix. In June 2007, this vaccine was licensed in Australia, and it was approved in the European Union in September 2007.[106] Cervarix was approved for use in the U.S. in October 2009.[107]

Harald zur Hausen, a German researcher who suspected, and later helped to prove that genital HPV infection can lead to cervical cancer, was awarded half of the $1.4 million Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2008 for his work. Verification that cervical cancer is caused by an infectious agent led several other groups to develop vaccines against HPV strains that cause most cases of cervical cancer. The other half of the award went to Françoise Barré-Sinoussi and Luc Montagnier, two French virologists, for their part in the discovery of HIV.[108]

Harald zur Hausen was skeptical of the prevailing dogma and postulated that oncogenic human papilloma virus (HPV) caused cervical cancer.[46] He realized that HPV-DNA could exist in an inactive state in the tumours, and should be detectable by specific searches for viral DNA.[108] He and workers at the Pasteur Institute found HPV to be a heterogeneous family of viruses. Only some HPV types cause cancer.[46]

Harald zur Hausen pursued his research for over ten years searching for different HPV types.[108] This research was difficult because only parts of the viral DNA were integrated into the host genome. He found novel HPV-DNA in cervix cancer biopsies, and thus discovered the new, tumourigenic HPV16 type in 1983. In 1984, he cloned HPV16 and 18 from patients with cervical cancer.[108] The HPV types 16 and 18 were consistently found in about 70% of cervical cancer biopsies throughout the world.[46]

His observation of HPV oncogenic potential in human malignancy provided impetus within the research community to characterize the natural history of HPV infection, and to develop a better understanding of mechanisms of HPV-induced carcinogenesis.[46]

In December 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a vaccine called Gardasil 9 to protect females between the ages of 9 and 26 and males between the ages of 9 and 15 against nine strains of HPV.[109] Gardasil 9 protects against infection from the strains covered by the first generation of Gardasil (HPV-6, HPV-11, HPV-16, and HPV-18) and protects against five other HPV strains responsible for 20% of cervical cancers (HPV-31, HPV-33, HPV-45, HPV-52, and HPV-58).[109]

Society and culture[edit]

Cost[edit]

As of 2013, vaccinating girls and young women was estimated to be cost-effective in the low and middle-income countries, especially in places without organized programs for screening cervical cancer.[30] When the cost of the vaccine itself, or the cost of administering it to individuals, were higher, or if cervical cancer screening were readily available, then vaccination was less likely to be cost-effective.

From a public health point of view, vaccinating men as well as women decreases the virus pool within the population, but is only cost-effective to vaccinate men when the uptake in the female population is extremely low.[110] In the United States, the cost per quality-adjusted life year is greater than US$100,000 for vaccinating the male population, compared to the less than US$50,000 for vaccinating the female population.[110] This assumes a 75% vaccination rate.

In 2013, the two companies who sell the most common vaccines announced a price cut to less than US$5 per dose to poor countries, as opposed to US$130 per dose in the U.S.[111]