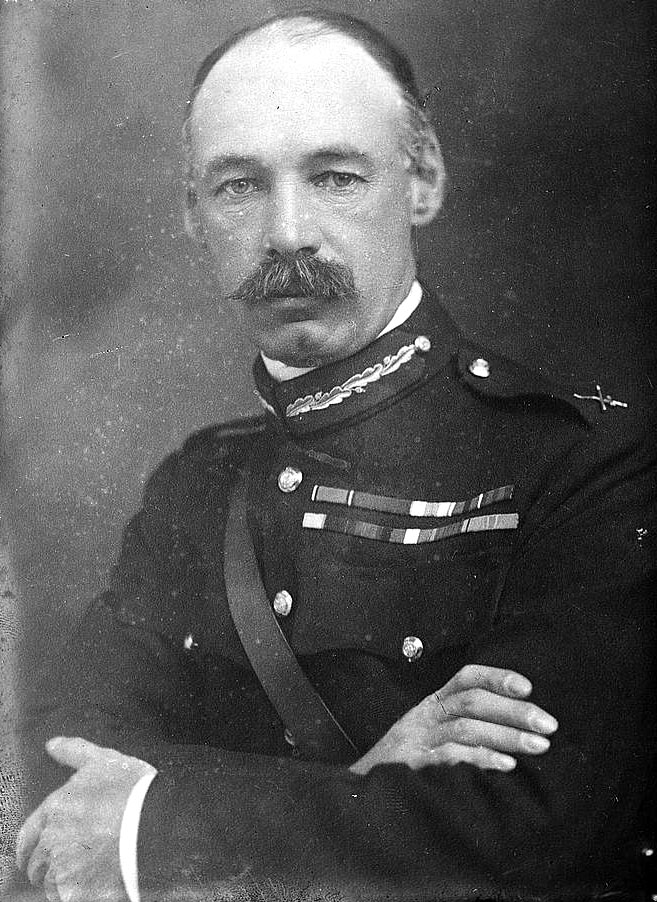

Henry Rawlinson, 1st Baron Rawlinson

General Henry Seymour Rawlinson, 1st Baron Rawlinson, GCB, GCSI, GCVO, KCMG, KStJ (20 February 1864 – 28 March 1925), known as Sir Henry Rawlinson, 2nd Baronet between 1895 and 1919, was a senior British Army officer in the First World War who commanded the Fourth Army of the British Expeditionary Force at the battles of the Somme (1916) and Amiens (1918) as well as the breaking of the Hindenburg Line (1918). He commanded the Indian Army from 1920 to 1925.

Not to be confused with his father, Sir Henry Rawlinson, 1st Baronet, a British diplomat and orientalist.

The Lord Rawlinson

20 February 1864

Trent Manor, Dorset, England

28 March 1925 (aged 61)

Delhi, British India

United Kingdom

1884–1925

Early life[edit]

Rawlinson was born at Trent Manor in Dorset on 20 February 1864.[1] His father, Sir Henry Rawlinson, 1st Baronet, was an Army officer, and a renowned Middle East scholar who is generally recognised as the father of Assyriology. His mother was Louisa Caroline Harcourt Seymour (1828-1889). He received his early formal education at Eton College.[2]

First World War[edit]

Western Front[edit]

In September 1914 Rawlinson was appointed General Officer Commanding 4th Division in France.[5] Promoted to temporary lieutenant-general on 4 October 1914,[25] he then took command of the IV Corps.[5] In late September, the Belgian government formally requested British military assistance in defending Antwerp. IV Corps, acting under orders from the Cabinet, was chosen to reinforce the city. Rawlinson arrived in Antwerp on 6 October.[26] It was soon obvious that the combined British, Belgian, and French forces were too weak to hold the city, and Kitchener decided on an evacuation two days later.[27] IV Corps and the remnants of the Belgian Army successfully re-joined Allied forces in Western Belgium, with the Cabinet returning Rawlinson's Corps to Sir John French's command.[28] IV Corps marched into Ypres on the night of 13–14 October, where the BEF, advancing northwards, was preparing to meet the German Army.[29] Located at the centre of the British line, IV Corps met the main thrust of the German attacks between 18 and 27 October and suffered heavy casualties.[30] On 28 October, IV Corps was put under the temporary command of Douglas Haig while Rawlinson went to England to oversee the preparation of 8th Division. When he returned in November the German attacks on Ypres had died down.[31]

Rawlinson wrote to the Conservative politician Lord Derby (24 December 1914) forecasting that the Allies would win a war of attrition but it was unclear whether this would take one, two or three years.[32] In 1915, IV Corps formed part of the First Army (General Douglas Haig). At the battle of Neuve Chapelle (10–12 March 1915), he massed 340 guns. The weight of this bombardment on a comparatively narrow front enabled the attackers to secure the village and 1,600 yd (1,500 m) of the German front line. The arrival of German reinforcements prevented further advance. Rawlinson concluded that an enemy's line of trenches could be broken 'with suitable artillery preparation' combined with secrecy.[33] He also drew a lesson, that trench warfare called for limited advances: 'What I want to do now is what I call "Bite & Hold" – bite off a piece of the enemy's line like Neuve Chapelle & hold it against all counter-attacks...there ought to be no difficulty in holding against the enemy's counterattacks & inflicting on him at least twice the loss that we have suffered in making the bite'.[34]

At the end of 1915, Rawlinson was considered for command of the First Army, in succession to Haig but the command was instead given to Sir Charles Monro. He was promoted to temporary general on 22 December 1915.[35] Promoted to the substantive rank of lieutenant-general on 1 January 1916,[36] Rawlinson assumed command of the new Fourth Army on 24 January 1916.[37] The Fourth Army would play a major role in the planned Allied offensive on the Somme. He wrote in his diary: "It is not the lot of many men to command an army of over half a million men".[38] The Somme was originally conceived as a joint Anglo-French offensive but owing to the demands of the Battle of Verdun, French participation was greatly reduced, leaving the British, and especially Rawlinson's inexperienced army, to bear the brunt of the offensive.[39] On the eve of the offensive, he "showed an attitude of absolute confidence".[40] To his diary he confided some uncertainties: "What the actual results will be no one can say but I feel pretty confident of success myself though only after heavy fighting. That the bosh [sic] will break and that a debacle will supervene I do not believe..." He was not satisfied that the wire was well cut and enemy trenches sufficiently "knocked about".[41]

Later life[edit]

Post-war activities[edit]

Rawlinson was bestowed with many honours in reward for his role in the First World War. He was made a Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order in 1917 and appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George 1918. In August 1919 the Houses of Parliament passed a vote of thanks to him for his military service, and awarded him the sum of £30,000 from the Exchequer.[64] In 1919, he was raised to the peerage as Baron Rawlinson of Trent in the County of Dorset,[65] and appointed a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath.[66]

Rawlinson was again called on to organise an evacuation, this time of the Allied forces that had been sent to Russia to intervene in the Russian Civil War.[5] In November 1919 he became General Officer Commanding-in-Chief for Aldershot Command.[5]

Indian Command[edit]

In 1920, Rawlinson was made Commander-in-Chief, India. Winston Churchill as Secretary of State for War was instrumental in securing his appointment, over-riding a tradition that the post alternated between officers from the British and Indian Armies. He told Lloyd George that the post should go to the best qualified officer and that his military advisors "entirely supported my view that the best appointment we could make would be that of General Lord Rawlinson".[67] He held the post until his death.[5] He faced severe challenges. Brigadier Reginald Dyer's ordering his men to shoot at a crowd at Amritsar, killing 387 unarmed Indians, left a deep legacy of bitterness.[68] The 3rd Afghan War had ended, but there was continued fighting in Waziristan. A hugely expanded army faced postwar demobilisation and continued cost of modernisation. The new commander-in-chief was expected to introduce a measure of "Indianisation", giving commissions to Indians. Under the system of Dyarchy, Indians, generally opposed to military expenditure, took a share in government and Rawlinson would have to justify army budgets. The Moplah Rebellion of 1921 brought widespread disorder. When Gandhi launched the movement of non-cooperation with the British on 1 August 1920, he wished to avoid popular violence, but in 1922 the campaign degenerated: a crowd attacked a police station at Chauri Chaura, set fire to the building and 22 or 23 policemen were burnt to death or hacked down by the crowd. Gandhi cancelled the campaign, but he and other leaders of the resistance were arrested.[69] Rawlinson certainly began his command believing that the Army would have to maintain order. On 15 July, he complained that:

John Newsinger argues that "there is no doubt that the great majority of the British in India, soldiers, officials, civilians, agreed with Rawlinson on this. A few months later he noted in his journal that he "was determined to fight for the white community against any black sedition or rebellion", and, if necessary, "be the next Dyer".[71] Nonetheless, with Gandhi temporarily behind bars and increasing economic stability as the 1920s advanced, Rawlinson had the scope to reduce the Army's strength, modernise its equipment and work closely with Viceroys Chelmsford and Reading to try to make dyarchy a success. In Waziristan, the British and Indian Field Force backed by aircraft put an end to the fighting, built roads and established a brigade base at Razmak.[72] Rawlinson announced a scheme of "Indianisation" to the Legislative Assembly on 17 February 1923. Its aim, he said, was to "give Indians a fair opportunity of providing that units officered by Indians will be efficient in every way". The Prince of Wales' Royal Indian Military College was founded at Dehra Dun in 1922, run on English public school lines, to encourage potential officer candidates.[73]

In 1924, Rawlinson was appointed a Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India. By the end of his Indian command, he had reduced the Indian army in numbers and cost, but improved firepower, mobility and training. In financial matters he had been hugely helped by Sir Bhupendra Mitra, who had financial details "at his finger's ends".[74] He had been appointed to succeed Lord Cavan as CIGS when he left India.[75]

Death[edit]

Rawlinson died on 28 March 1925 at the age of 61 at Delhi in India, after a medical operation for a stomach ailment, although not long before the operation he had played polo and cricket and seemed fit and well.[76] His body was carried back to England on the SS Assaye, which was met on reaching the English Channel by a Royal Navy destroyer, onto which the coffin was transferred, then carried into Portsmouth Harbour, being met at the South Jetty by a military ceremonial receiving party.[77] Rawlinson was buried in the chapel of St Michael and St George in the north transept of St Andrew's Church, Trent, in the county of Dorset.[78]

Personal life[edit]

Rawlinson was a gifted watercolour artist. In March 1920, he and Winston Churchill enjoyed a painting holiday together on the French estate of the Duke of Westminster. "The General paints in water colours and does it very well," wrote Churchill. "With all my enormous paraphernalia, I have produced very indifferent results here."[79] He married Meredith Sophia Francis Kennard (1861–1931) at St Paul's Church, Knightsbridge, London on 5 November 1890, the marriage producing no children. On Henry Rawlinson's death the baronetcy passed to his brother Alfred Rawlinson.[64][80]