Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria

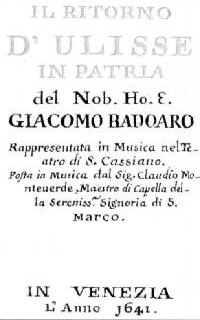

Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria (SV 325, The Return of Ulysses to his Homeland) is an opera consisting of a prologue and five acts (later revised to three), set by Claudio Monteverdi to a libretto by Giacomo Badoaro. The opera was first performed at the Teatro Santi Giovanni e Paolo in Venice during the 1639–1640 carnival season. The story, taken from the second half of Homer's Odyssey,[n 1] tells how constancy and virtue are ultimately rewarded, treachery and deception overcome. After his long journey home from the Trojan Wars Ulisse, king of Ithaca, finally returns to his kingdom where he finds that a trio of villainous suitors are importuning his faithful queen, Penelope. With the assistance of the gods, his son Telemaco and a staunch friend Eumete, Ulisse vanquishes the suitors and recovers his kingdom.

Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria

Italian

Il ritorno is the first of three full-length works which Monteverdi wrote for the burgeoning Venetian opera industry during the last five years of his life. After its initial successful run in Venice the opera was performed in Bologna before returning to Venice for the 1640–41 season. Thereafter, except for a possible performance at the Imperial court in Vienna late in the 17th century, there were no further revivals until the 20th century. The music became known in modern times through the 19th-century discovery of an incomplete manuscript score which in many respects is inconsistent with the surviving versions of the libretto. After its publication in 1922 the score's authenticity was widely questioned, and performances of the opera remained rare during the next 30 years. By the 1950s the work was generally accepted as Monteverdi's, and after revivals in Vienna and Glyndebourne in the early 1970s it became increasingly popular. It has since been performed in opera houses all over the world, and has been recorded many times.

Together with Monteverdi's other Venetian stage works, Il ritorno is classified as one of the first modern operas. Its music, while showing the influence of earlier works, also demonstrates Monteverdi's development as a composer of opera, through his use of fashionable forms such as arioso, duet and ensemble alongside the older-style recitative. By using a variety of musical styles, Monteverdi is able to express the feelings and emotions of a great range of characters, divine and human, through their music. Il ritorno has been described as an "ugly duckling", and conversely as the most tender and moving of Monteverdi's surviving operas, one which although it might disappoint initially, will on subsequent hearings reveal a vocal style of extraordinary eloquence.

Music[edit]

According to Denis Arnold, although Monteverdi's late operas retain elements of the earlier Renaissance intermezzo and pastoral forms, they may be fairly considered as the first modern operas.[50] In the 1960s, however, David Johnson found it necessary to warn prospective Il ritorno listeners that if they expected to hear opera akin to Verdi, Puccini or Mozart, they would be disappointed: "You have to submit yourself to a much slower pace, to a much more chaste conception of melody, to a vocal style that is at first or second hearing merely like dry declamation and only on repeated hearings begins to assume an extraordinary eloquence."[51] A few years later, Jeremy Noble in a Gramophone review wrote that Il ritorno was the least known and least performed of Monteverdi's operas, "quite frankly, because its music is not so consistently full of character and imagination as that of Orfeo or Poppea."[52] Arnold called the work an "ugly duckling".[53] Later analysts have been more positive; to Mark Ringer Il ritorno is "the most tender and moving of Monteverdi's operas",[54] while in Ellen Rosand's view the composer's ability to portray real human beings through music finds its fullest realisation here, and in Poppea a few years later.[13]

The music of Il ritorno shows the unmistakable influence of the composer's earlier works. Penelope's lament, which opens Act I, is reminiscent both of Orfeo's Redentemi il mio ben and the lament from L'Arianna. The martial-sounding music which accompanies references to battles and the killing of the suitors, derives from Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda, while for the song episodes in Il ritorno Monteverdi draws in part on the techniques which he developed in his 1632 vocal work Scherzi musicale.[55] In typical Monteverdi fashion the opera's characters are vividly portrayed in their music.[53] Penelope and Ulisse, with what is described by Ringer as "honest musical and verbal declamation", overcome the suitors whose styles are "exaggerated and ornamental".[54] Iro, perhaps "the first great comic character in opera",[56] opens his Act 3 monologue with a wail of distress that stretches across eight bars of music.[57] Penelope begins her lament with a reiteration of E flats that, according to Ringer, "suggest a sense of motionless and emotional stasis" that well represents her condition as the opera begins.[56] At the work's end, her travails over, she unites with Ulisse in a duet of life-affirming confidence which, Ringer suggests, no other composer bar Verdi could have achieved.[58]

Rosand divides the music of Il ritorno into "speech-like" and "musical" utterances. Speech, usually in the form of recitative, delivers information and moves the action forward, while musical utterances, either formal songs or occasional short outbursts, are lyrical passages that enhance an emotional or dramatic situation.[59] This division is, however, less formal than in Monteverdi's earlier L'Orfeo; in Il ritorno information is frequently conveyed through the use of arioso, or even aria at times, increasing both tunefulness and tonal unity.[25] As with Orfeo and Poppea, Monteverdi differentiates musically between humans and gods, with the latter singing music which is usually more profusely melodic—although in Il ritorno, most of the human characters have some opportunity for lyrical expression.[12] According to the reviewer Iain Fenlon, "it is Monteverdi's mellifluous and flexible recitative style, capable of easy movement between declamation and arioso, which remains in the memory as the dominant language of the work."[60] Monteverdi's ability to combine fashionable forms such as the chamber duet and ensembles with the older-style recitative from earlier in the century further illustrate the development of the composer's dramatic style.[47][50] Monteverdi's trademark feature of "stilo concitato" (rapid repetition of notes to suggest dramatic action or excitement) is deployed to good effect in the fight scene between Ulisse and Iro, and in the slaying of the suitors.[61][62] Arnold draws attention to the great range of characters in the opera—the divine, the noble, the servants, the evil, the foolish, the innocent and the good. For all of these "the music expresses their emotions with astonishing accuracy."[50]

Since the publication of the Vienna manuscript score in 1922 the opera has been edited frequently, sometimes for specific performances or recordings. The following are the main published editions of the work, to 2010.