Index (publishing)

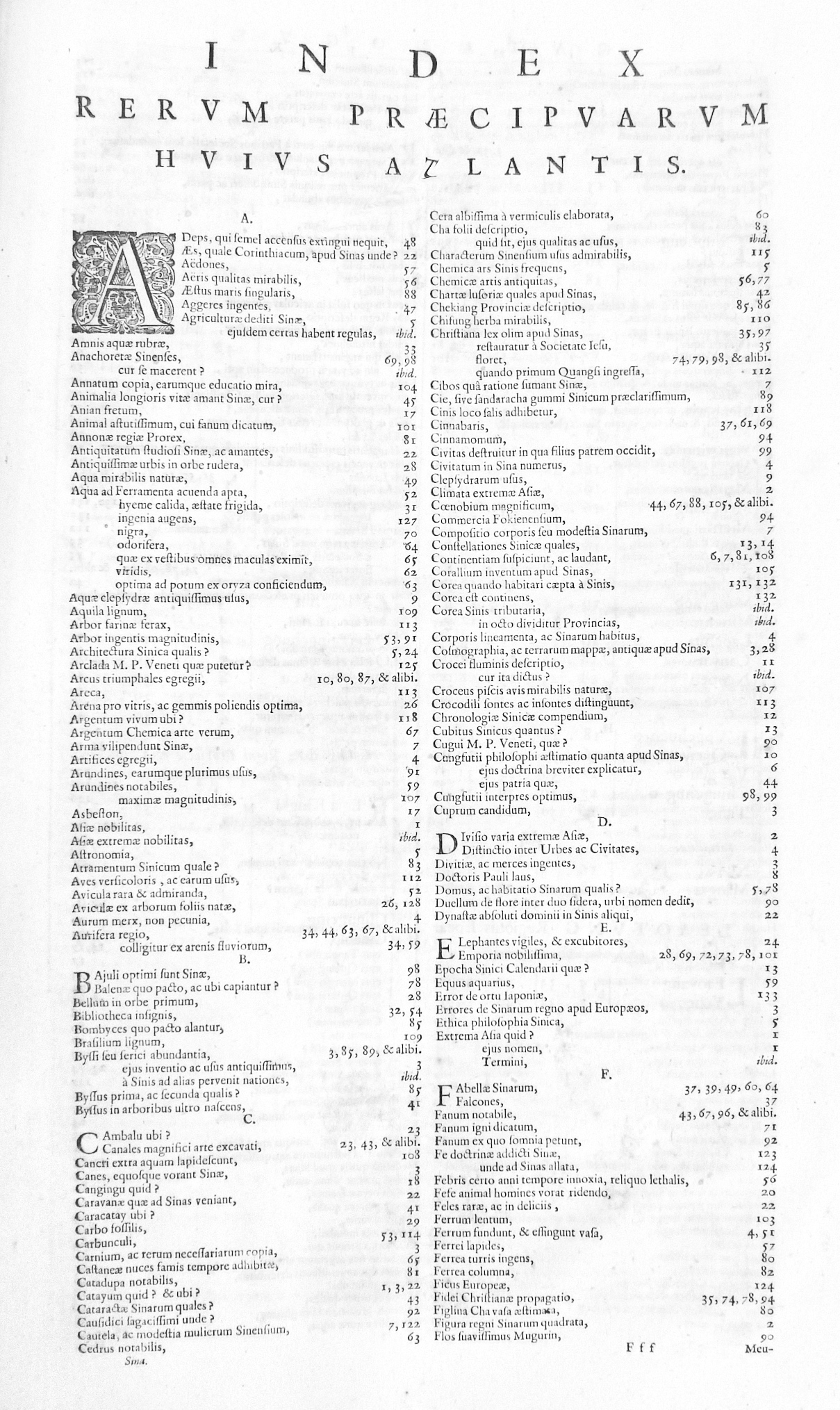

An index (pl.: usually indexes, more rarely indices) is a list of words or phrases ('headings') and associated pointers ('locators') to where useful material relating to that heading can be found in a document or collection of documents. Examples are an index in the back matter of a book and an index that serves as a library catalog. An index differs from a word index, or concordance, in focusing on the subject of the text rather than the exact words in a text, and it differs from a table of contents because the index is ordered by subject, regardless of whether it is early or late in the book, while the listed items in a table of contents is placed in the same order as the book.[1]

In a traditional back-of-the-book index, the headings will include names of people, places, events, and concepts selected as being relevant and of interest to a possible reader of the book. The indexer performing the selection may be the author, the editor, or a professional indexer working as a third party. The pointers are typically page numbers, paragraph numbers or section numbers.

In a library catalog the words are authors, titles, subject headings, etc., and the pointers are call numbers. Internet search engines (such as Google) and full-text searching help provide access to information but are not as selective as an index, as they provide non-relevant links, and may miss relevant information if it is not phrased in exactly the way they expect.[2]

Perhaps the most advanced investigation of problems related to book indexes is made in the development of topic maps, which started as a way of representing the knowledge structures inherent in traditional back-of-the-book indexes. The concept embodied by book indexes lent its name to database indexes, which similarly provide an abridged way to look up information in a larger collection, albeit one for computer use rather than human use.

Etymology and plural[edit]

The word is derived from Latin, in which index means "one who points out", an "indication", or a "forefinger".

In Latin, the plural form of the word is indices. In English, the plural "indices" is commonly used in mathematical and computing contexts, and sometimes in bibliographical contexts – for example, in the 17-volume Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia (1999–2002).[5] However, this form is now seen as an archaism by many writers and commentators, who prefer the anglicised plural "indexes". "Indexes" is widely used in the publishing industry; in the International Standard ISO 999, Information and documentation – Guidelines for the content, organization and presentation of indexes; and is preferred by the Oxford Style Manual.[6] The Chicago Manual of Style allows both forms.[7]

G. Norman Knight quotes Shakespeare's lines from Troilus and Cressida (I.3.344) – "And in such indexes ..." – and comments:

"But the real importance of this passage is that it establishes for all time the correct literary plural; we can leave the Latin form "indices" to the mathematicians (and similarly "appendices" to the anatomists)."[3]

Indexing process[edit]

Conventional indexing[edit]

The indexer reads through the text, identifying indexable concepts (those for which the text provides useful information and which will be of relevance for the text's readership). The indexer creates index headings to represent those concepts, which are phrased such that they can be found when in alphabetical order (so, for example, one would write 'indexing process' rather than 'how to create an index'). These headings and their associated locators (indicators to position in the text) are entered into specialist indexing software which handles the formatting of the index and facilitates the editing phase. The index is then edited to impose consistency throughout the index.

Indexers must analyze the text to enable presentation of concepts and ideas in the index that may not be named within the text. The index is intended to help the reader, researcher, or information professional, rather than the author, find information, so the professional indexer must act as a liaison between the text and its ultimate user.

In the United States, according to tradition, the index for a non-fiction book is the responsibility of the author, but most authors do not actually do it. Most indexing is done by freelancers hired by authors, publishers or an independent business which manages the production of a book,[8] publishers or book packagers. Some publishers and database companies employ indexers.

Before indexing software existed, indexes were created using slips of paper or, later, index cards. After hundreds of such slips or cards were filled out (as the indexer worked through the pages of the book proofs), they could then be shuffled by hand into alphabetical order, at which point they served as manuscript to be typeset into the printed index.

Some principles of good indexing include:[12]

Indexing pitfalls:

Indexer roles[edit]

Some indexers specialize in specific formats, such as scholarly books, microforms, web indexing (the application of a back-of-book-style index to a website or intranet), search engine indexing, database indexing (the application of a pre-defined controlled vocabulary such as MeSH to articles for inclusion in a database), and periodical indexing[13] (indexing of newspapers, journals, magazines).

Some indexers with expertise in controlled vocabularies also work as taxonomists and ontologists.

Some indexers specialize in particular subject areas, such as anthropology, business, computers, economics, education, government documents, history, law, mathematics, medicine, psychology, and technology. An indexer can be found for any subject.

References in popular culture[edit]

In "The Library of Babel", a short story by Jorge Luis Borges, there is an index of indexes that catalogues all of the books in the library, which contains all possible books.

Kurt Vonnegut's novel Cat's Cradle includes a character who is a professional indexer and believes that "indexing [is] a thing that only the most amateurish author [undertakes] to do for his own book." She claims to be able to read an author's character through the index he created for his own history text, and warns the narrator, an author, "Never index your own book."

Vladimir Nabokov's novel Pale Fire includes a parody of an index, reflecting the insanity of the narrator.

Mark Danielewski's novel House of Leaves contains an exhaustive 41 page index of words in the novel, including even large listings for inconsequential words such as the, and, and in.

J. G. Ballard's "The Index" is a short story told through the form of an index to an "unpublished and perhaps suppressed" autobiography.[14]

The American Society for Indexing, Inc. (ASI) is a national association founded in 1968 to promote excellence in indexing and increase awareness of the value of well-designed indexes. ASI serves indexers, librarians, abstractors, editors, publishers, database producers, data searchers, product developers, technical writers, academic professionals, researchers and readers, and others concerned with indexing. It is the only professional organization in the United States devoted solely to the advancement of indexing, abstracting and related methods of information retrieval.

Other similar societies include: