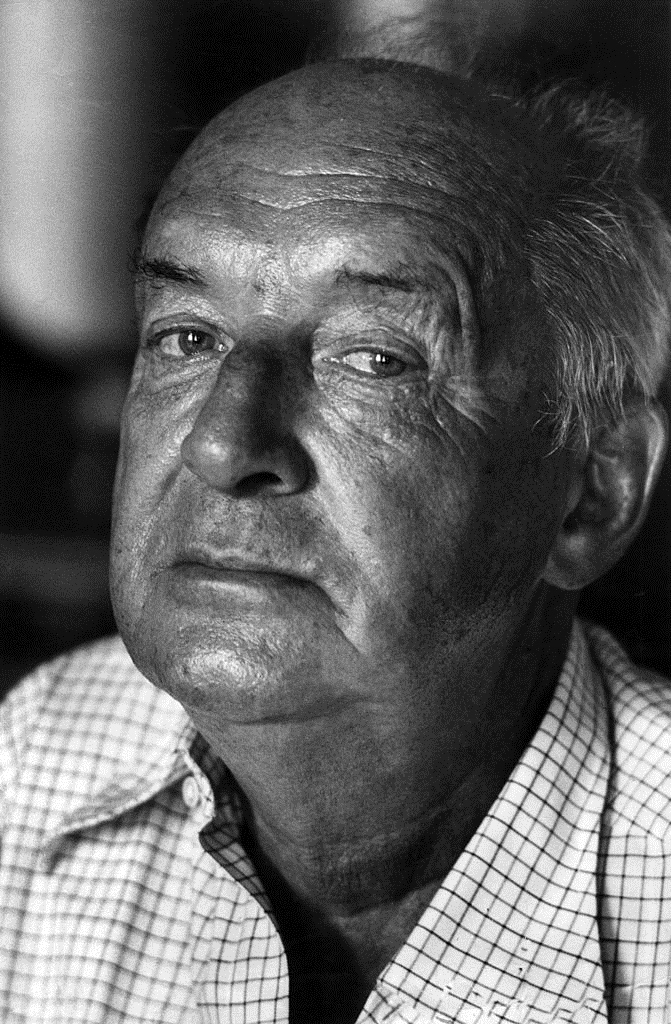

Vladimir Nabokov

Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov[b] (Russian: Владимир Владимирович Набоков [vlɐˈdʲimʲɪr vlɐˈdʲimʲɪrəvʲɪtɕ nɐˈbokəf] ⓘ; 22 April [O.S. 10 April] 1899[a] – 2 July 1977), also known by the pen name Vladimir Sirin (Владимир Сирин), was an expatriate Russian and Russian-American novelist, poet, translator, and entomologist. Born in Imperial Russia in 1899, Nabokov wrote his first nine novels in Russian (1926–1938) while living in Berlin, where he met his wife. He achieved international acclaim and prominence after moving to the United States, where he began writing in English. Nabokov became an American citizen in 1945 and lived mostly on the East Coast before returning to Europe in 1961, where he settled in Montreux, Switzerland.

"Nabokov" redirects here. For his father, the politician, see Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov. For other persons with the name, see Nabokov (surname).

Vladimir Nabokov

22 April [O.S. 10 April] 1899[a]

Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire

2 July 1977 (aged 78)

Montreux, Switzerland

Vladimir Sirin

- Novelist

- poet

- literary critic

- entomologist

- professor

- Russian

- English

- French

- Russian Empire →

- United States

- Switzerland

- Novel

- novella

- short story

- play

- poetry

- translation

- autobiography

- non-fiction

from 1916

- The Defense (1930)

- Despair (1934)

- Invitation to a Beheading (1936)

- The Gift (1938)

- The Enchanter (1939)

- "Signs and Symbols" (1948)

- Lolita (1955)

- Pnin (1957)

- Pale Fire (1962)

- Speak, Memory (1936–1966)

- Ada or Ardor (1969)

From 1948 to 1959, Nabokov was a professor of Russian literature at Cornell University.[6] His 1955 novel Lolita ranked fourth on Modern Library's list of the 100 best 20th-century novels in 2007 and is considered one of the greatest works of 20th-century literature.[7] Nabokov's Pale Fire, published in 1962, ranked 53rd on the same list. His memoir, Speak, Memory, published in 1951, is considered among the greatest nonfiction works of the 20th century, placing eighth on Random House's ranking of 20th-century works.[8] Nabokov was a seven-time finalist for the National Book Award for Fiction. He also was an expert lepidopterist and composer of chess problems.

Career[edit]

Berlin (1922–1937)[edit]

In 1920, Nabokov's family moved to Berlin, where his father set up the émigré newspaper Rul' ("Rudder"). Nabokov followed them to Berlin two years later, after completing his studies at Cambridge.

In March 1922, Russian monarchists Pyotr Shabelsky-Bork and Sergey Taboritsky shot and killed Nabokov's father in Berlin as he was shielding their target, Pavel Milyukov, a leader of the Constitutional Democratic Party-in-exile. Shortly after his father's death, Nabokov's mother and sister moved to Prague. Nabokov drew upon his father's death repeatedly in his fiction. On one interpretation of his novel Pale Fire, an assassin kills the poet John Shade when his target is a fugitive European monarch.

Nabokov stayed in Berlin, where he had become a recognised poet and writer in Russian within the émigré community; he published under the nom de plume V. Sirin (a reference to the fabulous bird of Russian folklore). To supplement his scant writing income, he taught languages and gave tennis and boxing lessons.[19] Dieter E. Zimmer has written of Nabokov's 15 Berlin years, "he never became fond of Berlin, and at the end intensely disliked it. He lived within the lively Russian community of Berlin that was more or less self-sufficient, staying on after it had disintegrated because he had nowhere else to go to. He knew little German. He knew few Germans except for landladies, shopkeepers, and immigration officials at the police headquarters."[20]

Entomology[edit]

Nabokov's interest in entomology was inspired by books by Maria Sibylla Merian he found in the attic of his family's country home in Vyra.[64] Throughout an extensive career of collecting, he never learned to drive a car, and depended on his wife to take him to collecting sites. During the 1940s, as a research fellow in zoology, he was responsible for organizing the butterfly collection of Harvard University's Museum of Comparative Zoology. His writings in this area were highly technical. This, combined with his specialty in the relatively unspectacular tribe Polyommatini of the family Lycaenidae, has left this facet of his life little explored by most admirers of his literary works. He described the Karner blue. The genus Nabokovia was named after him in honor of this work, as were a number of butterfly and moth species (e.g., many species in the genera Madeleinea and Pseudolucia bear epithets alluding to Nabokov or names from his novels).[65] In 1967, Nabokov commented: "The pleasures and rewards of literary inspiration are nothing beside the rapture of discovering a new organ under the microscope or an undescribed species on a mountainside in Iran or Peru. It is not improbable that had there been no revolution in Russia, I would have devoted myself entirely to lepidopterology and never written any novels at all."[31]

The paleontologist and essayist Stephen Jay Gould discussed Nabokov's lepidoptery in his essay "No Science Without Fancy, No Art Without Facts: The Lepidoptery of Vladimir Nabokov" (reprinted in I Have Landed). Gould notes that Nabokov was occasionally a scientific "stick-in-the-mud". For example, Nabokov never accepted that genetics or the counting of chromosomes could be a valid way to distinguish species of insects, and relied on the traditional (for lepidopterists) microscopic comparison of their genitalia.

The Harvard Museum of Natural History, which now contains the Museum of Comparative Zoology, still possesses Nabokov's "genitalia cabinet", where the author stored his collection of male blue butterfly genitalia.[66][67] "Nabokov was a serious taxonomist," says museum staff writer Nancy Pick, author of The Rarest of the Rare: Stories Behind the Treasures at the Harvard Museum of Natural History. "He actually did quite a good job at distinguishing species that you would not think were different—by looking at their genitalia under a microscope six hours a day, seven days a week, until his eyesight was permanently impaired."[67] The rest of his collection, about 4,300 specimens, was given to the Lausanne's Museum of Zoology in Switzerland.

Though professional lepidopterists did not take Nabokov's work seriously during his life, new genetic research supports Nabokov's hypothesis that a group of butterfly species, called the Polyommatus blues, came to the New World over the Bering Strait in five waves, eventually reaching Chile.[68]

Many of Nabokov's fans have tried to ascribe literary value to his scientific papers, Gould notes. Conversely, others have claimed that his scientific work enriched his literary output. Gould advocates a third view, holding that the other two positions are examples of the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy. Rather than assuming that either side of Nabokov's work caused or stimulated the other, Gould proposes that both stemmed from Nabokov's love of detail, contemplation, and symmetry.

Personal life[edit]

Synesthesia[edit]

Nabokov was a self-described synesthete, who at a young age equated the number five with the color red.[83] Aspects of synesthesia can be found in several of his works. His wife also exhibited synesthesia; like her husband, her mind's eye associated colors with particular letters. They discovered that Dmitri shared the trait, and moreover that the colors he associated with some letters were in some cases blends of his parents' hues—"which is as if genes were painting in aquarelle".[84] Nabokov also wrote that his mother had synesthesia, and that she had different letter-color pairs.[85]

For some synesthetes, letters are not simply associated with certain colors, they are themselves colored. Nabokov frequently endowed his protagonists with a similar gift. In Bend Sinister, Krug comments on his perception of the word "loyalty" as like a golden fork lying out in the sun. In The Defense, Nabokov briefly mentions that the main character's father, a writer, found he was unable to complete a novel that he planned to write, becoming lost in the fabricated storyline by "starting with colors". Many other subtle references are made in Nabokov's writing that can be traced back to his synesthesia. Many of his characters have a distinct "sensory appetite" reminiscent of synesthesia.[86]

Nabokov described his synesthesia at length in his autobiography Speak, Memory:[87]