International humanitarian law

International humanitarian law (IHL), also referred to as the laws of armed conflict, is the law that regulates the conduct of war (jus in bello).[1][2] It is a branch of international law that seeks to limit the effects of armed conflict by protecting persons who are not participating in hostilities and by restricting and regulating the means and methods of warfare available to combatants.

Not to be confused with International human rights law.

International humanitarian law is inspired by considerations of humanity and the mitigation of human suffering. It comprises a set of rules, which is established by treaty or custom and that seeks to protect persons and property/objects that are or may be affected by armed conflict, and it limits the rights of parties to a conflict to use methods and means of warfare of their choice.[3] Sources of international law include international agreements (the Geneva Conventions), customary international law, general principles of nations, and case law.[2][4] It defines the conduct and responsibilities of belligerent nations, neutral nations, and individuals engaged in warfare, in relation to each other and to protected persons, usually meaning non-combatants. It is designed to balance humanitarian concerns and military necessity, and subjects warfare to the rule of law by limiting its destructive effect and alleviating human suffering.[3] Serious violations of international humanitarian law are called war crimes.

While IHL (jus in bello) concerns the rules and principles governing the conduct of warfare once armed conflict has begun, jus ad bellum pertains to the justification for resorting to war and includes the crime of aggression. Together the jus in bello and jus ad bellum comprise the two strands of the laws of war governing all aspects of international armed conflicts. The law is mandatory for nations bound by the appropriate treaties. There are also other customary unwritten rules of war, many of which were explored at the Nuremberg trials. IHL operates on a strict division between rules applicable in international armed conflict and internal armed conflict.[5]

International humanitarian law is traditionally seen as distinct from international human rights law (which governs the conduct of a state towards its people), although the two branches of law are complementary and in some ways overlap.[6][7][8]

Modern international humanitarian law is made up of two historical streams:

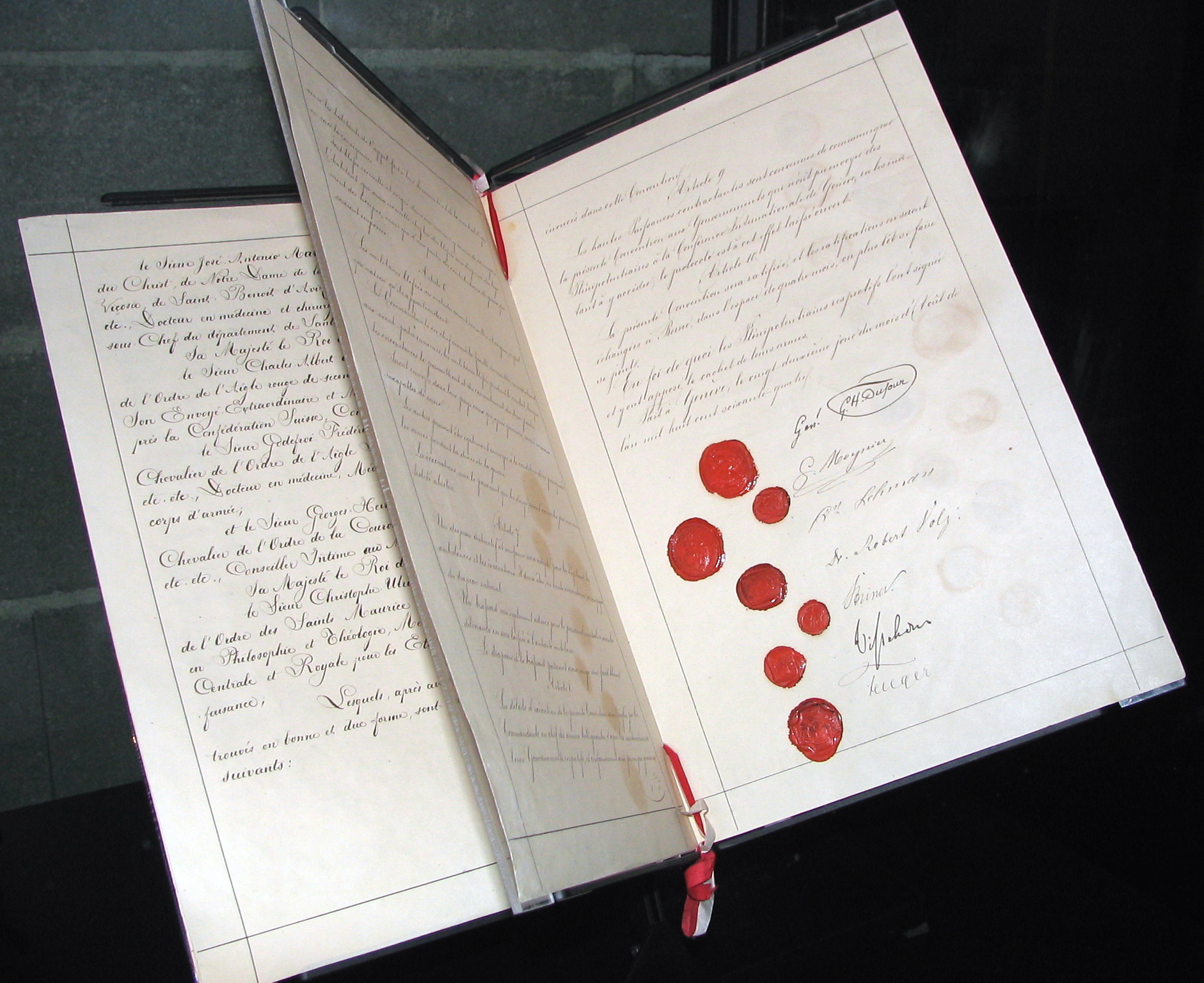

The two streams take their names from a number of international conferences which drew up treaties relating to war and conflict, in particular the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, and the Geneva Conventions, the first of which was drawn up in 1863. Both deal with jus in bello, which deals with the question of whether certain practices are acceptable during armed conflict.[10]

The Law of The Hague, or the laws of war proper, "determines the rights and duties of belligerents in the conduct of operations and limits the choice of means in doing harm".[11] In particular, it concerns itself with

Systematic attempts to limit the savagery of warfare only began to develop in the 19th century. Such concerns were able to build on the changing view of warfare by states influenced by the Age of Enlightenment. The purpose of warfare was to overcome the enemy state, which could be done by disabling the enemy combatants. Thus, "the distinction between combatants and civilians, the requirement that wounded and captured enemy combatants must be treated humanely, and that quarter must be given, some of the pillars of modern humanitarian law, all follow from this principle".[13]

The Geneva Conventions are the result of a process that developed in a number of stages between 1864 and 1949. It focused on the protection of civilians and those who can no longer fight in an armed conflict. As a result of World War II, all four conventions were revised, based on previous revisions and on some of the 1907 Hague Conventions, and readopted by the international community in 1949. Later conferences have added provisions prohibiting certain methods of warfare and addressing issues of civil wars.[26]

The first three Geneva Conventions were revised, expanded, and replaced, and the fourth one was added, in 1949.

There are three additional amendment protocols to the Geneva Convention:

The Geneva Conventions of 1949 may be seen, therefore, as the result of a process which began in 1864. Today they have "achieved universal participation with 194 parties". This means that they apply to almost any international armed conflict.[30] The Additional Protocols, however, have yet to achieve near-universal acceptance, since the United States and several other significant military powers (like Iran, Israel, India and Pakistan) are currently not parties to them.[31]

Historical convergence between IHL and the laws of war[edit]

With the adoption of the 1977 Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions, the two strains of law began to converge, although provisions focusing on humanity could already be found in the Hague law (i.e. the protection of certain prisoners of war and civilians in occupied territories). The 1977 Additional Protocols, relating to the protection of victims in both international and internal conflict, not only incorporated aspects of both the Law of The Hague and the Law of Geneva, but also important human rights provisions.[32]

International humanitarian law now includes several treaties that outlaw specific weapons. These conventions were created largely because these weapons cause deaths and injuries long after conflicts have ended. Unexploded land mines have caused up to 7,000 deaths a year; unexploded bombs, particularly from cluster bombs that scatter many small "bomblets", have also killed many. An estimated 98% of the victims are civilian; farmers tilling their fields and children who find these explosives have been common victims. For these reasons, the following conventions have been adopted:

Violations and punishment[edit]

During conflict, punishment for violating the laws of war may consist of a specific, deliberate and limited violation of the laws of war in reprisal.

Combatants who break specific provisions of the laws of war lose the protections and status afforded to them as prisoners of war, but only after facing a "competent tribunal".[35] At that point, they become unlawful combatants, but must still be "treated with humanity and, in case of trial, shall not be deprived of the rights of fair and regular trial", because they are still covered by GC IV, Article 5.

Spies and terrorists are only protected by the laws of war if the "power" which holds them is in a state of armed conflict or war, and until they are found to be an "unlawful combatant". Depending on the circumstances, they may be subject to civilian law or a military tribunal for their acts. In practice, they have often have been subjected to torture and execution. The laws of war neither approve nor condemn such acts, which fall outside their scope. Spies may only be punished following a trial; if captured after rejoining their own army, they must be treated as prisoners of war.[36] Suspected terrorists who are captured during an armed conflict, without having participated in the hostilities, may be detained only in accordance with the GC IV, and are entitled to a regular trial.[37] Countries that have signed the UN Convention Against Torture have committed themselves not to use torture on anyone for any reason.

After a conflict has ended, persons who have committed any breach of the laws of war, and especially atrocities, may be held individually accountable for war crimes through process of law.

Reparation for victims of serious violations of International Humanitarian Law acknowledges the suffering endured by individuals and communities and seeks to provide a form of redress for the harms inflicted upon them. The evolving legal landscape, notably through the mechanisms of international courts like the ICC, has reinforced the notion that victims of war crimes and other serious breaches of International Humanitarian Law have a recognized right to seek reparations. These reparations can take various forms, including restitution, compensation, rehabilitation, satisfaction, and guarantees of non-repetition, aimed at addressing the physical, psychological, and material damage suffered by victims.[38]

Sex and culture[edit]

Sex[edit]

IHL emphasises, in various provisions in the GCs and APs, the concept of formal equality and non-discrimination. Protections should be provided "without any adverse distinction founded on sex". For example, with regard to female prisoners of war, women are required to receive treatment "as favourable as that granted to men".[55] In addition to claims of formal equality, IHL mandates special protections to women, providing female prisoners of war with separate dormitories from men, for example,[56] and prohibiting sexual violence against women.[57]

The reality of women's and men's lived experiences of conflict has highlighted some of the gender limitations of IHL. Feminist critics have challenged IHL's focus on male combatants and its relegation of women to the status of victims, and its granting them legitimacy almost exclusively as child-rearers. A study of the 42 provisions relating to women within the Geneva Conventions and the Additional Protocols found that almost half address women who are expectant or nursing mothers.[58] Others have argued that the issue of sexual violence against men in conflict has not yet received the attention it deserves.[59]

Soft-law instruments have been relied on to supplement the protection of women in armed conflict: