Interplanetary contamination

Interplanetary contamination refers to biological contamination of a planetary body by a space probe or spacecraft, either deliberate or unintentional.

There are two types of interplanetary contamination:

The main focus is on microbial life and on potentially invasive species. Non-biological forms of contamination have also been considered, including contamination of sensitive deposits (such as lunar polar ice deposits) of scientific interest.[1] In the case of back contamination, multicellular life is thought unlikely but has not been ruled out. In the case of forward contamination, contamination by multicellular life (e.g. lichens) is unlikely to occur for robotic missions, but it becomes a consideration in crewed missions to Mars.[2]

Current space missions are governed by the Outer Space Treaty and the COSPAR guidelines for planetary protection. Forward contamination is prevented primarily by sterilizing the spacecraft. In the case of sample-return missions, the aim of the mission is to return extraterrestrial samples to Earth, and sterilization of the samples would make them of much less interest. So, back contamination would be prevented mainly by containment, and breaking the chain of contact between the planet of origin and Earth. It would also require quarantine procedures for the materials and for anyone who comes into contact with them.

Overview[edit]

Most of the Solar System appears hostile to life as we know it. No extraterrestrial life has ever been discovered. But if extraterrestrial life exists, it may be vulnerable to interplanetary contamination by foreign microorganisms. Some extremophiles may be able to survive space travel to another planet, and foreign life could possibly be introduced by spacecraft from Earth. If possible, some believe this poses scientific and ethical concerns.

Locations within the Solar System where life might exist today include the oceans of liquid water beneath the icy surface of Europa, Enceladus,

and Titan (its surface has oceans of liquid ethane / methane, but it may also have liquid water below the surface and ice volcanoes).[3][4]

There are multiple consequences for both forward- and back-contamination. If a planet becomes contaminated with Earth life, it might then be difficult to tell whether any lifeforms discovered originated there or came from Earth.[5] Furthermore, the organic chemicals produced by the introduced life would confuse sensitive searches for biosignatures of living or ancient native life. The same applies to other more complex biosignatures. Life on other planets could have a common origin with Earth life, since in the early Solar System there was much exchange of material between the planets which could have transferred life as well. If so, it might be based on nucleic acids too (RNA or DNA).

The majority of the species isolated are not well understood or characterized and cannot be cultured in labs, and are known only from DNA fragments obtained with swabs.[6] On a contaminated planet, it might be difficult to distinguish the DNA of extraterrestrial life from the DNA of life brought to the planet by the exploring. Most species of microorganisms on Earth are not yet well understood or DNA sequenced. This particularly applies to the unculturable archaea, and so are difficult to study. This can be either because they depend on the presence of other microorganisms, are slow growing, or depend on other conditions not yet understood. In typical habitats, 99% of microorganisms are not culturable.[7] Introduced Earth life could contaminate resources of value for future human missions, such as water.[8]

Invasive species could out compete native life or consume it, if there is life on the planet.[9] However, the experience on earth shows that species moved from one continent to another may be able to out compete the native life adapted to that continent.[9] Additionally, evolutionary processes on Earth might have developed biological pathways different from extraterrestrial organisms, and so may be able to out-compete it. The same is also possible the other way around for contamination introduced to Earth's biosphere.

In addition to science research concerns, there are also attempts to raise ethical and moral concerns regarding intentional or unintentional interplanetary transport of life.[10][11][12][13]

Crewed spacecraft[edit]

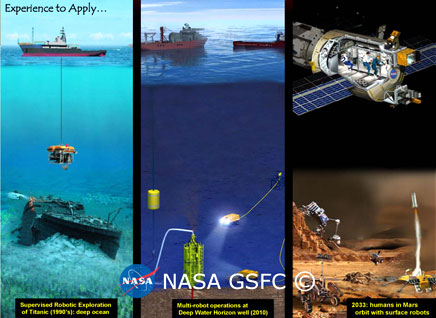

Crewed spacecraft are of particular concern for interplanetary contamination because of the impossibility to sterilize a human to the same level as a robotic spacecraft. Therefore, the chance of forwarding contamination is higher than for a robotic mission.[44] Humans are typically host to a hundred trillion microorganisms in ten thousand species in the human microbiome which cannot be removed while preserving the life of the human. Containment seems the only option, but effective containment to the same standard as a robotic rover appears difficult to achieve with present-day technology. In particular, adequate containment in the event of a hard landing is a major challenge.

Human explorers may be potential carriers back to Earth of microorganisms acquired on Mars, if such microorganisms exist.[45] Another issue is the contamination of the water supply by Earth microorganisms shed by humans in their stools, skin and breath, which could have a direct effect on the long-term human colonization of Mars.[8]

The Moon as a testbed[edit]

The Moon has been suggested as a testbed for new technology to protect sites in the Solar System, and astronauts, from forward and back contamination. Currently, the Moon has no contamination restrictions because it is considered to be "not of interest" for prebiotic chemistry and origins of life. Analysis of the contamination left by the Apollo program astronauts could also yield useful ground truth for planetary protection models.[46][47]