Israeli permit regime in the West Bank

The Israeli permit regime in the West Bank is the legal regime that requires Palestinians to obtain a number of separate permits from the Israeli military authorities governing Palestinians in the Israeli-occupied West Bank for a wide range of activities.[1][2][a] The first military order requiring permits for the Palestinians was issued before the end of the 1967 Six-Day War. The two uprisings of 1987 and 2001 were met by increased security measures, differentiation of IDs into green and red, policies of village closures, curfews and more stringent restrictions on Palestinian movement, with the general exit permit of 1972 replaced by individual permits. The stated Israeli justification for this new permit regime regarding movements was to contain the expansion of the uprisings and protect both the IDF and Israeli civilians from military confrontations with armed Palestinians.[3] The regime has since expanded to 101 different types of permits covering nearly every aspect of Palestinian life,[4][5] governing movement in Israel and in Israeli settlements, transit between Gaza and the West Bank, movement in Jerusalem and the seam zone, and travel abroad via international borders.[6] The Israeli High Court has rejected petitions against the permit regime, allowing that it severely impinges on the rights of Palestinian residents but that the harm was proportionate.[7]

Considered an example of racial profiling by scholars like Ronit Lentin, Yael Berda and others,[8][9][10] the regime has been characterized as arbitrary and as one that turned such rights as freedom of movement into mere privileges that could be granted or revoked by the military authority.[11] The regime itself has been likened to the South African pass laws under apartheid,[b][12][13][14][15] with Jennifer Loewenstein writing that the regime is "more complex and ruthlessly enforced than the pass system of the apartheid regime."[16] Israel has defended the permit regime as necessary to protect Israelis in the West Bank against what it describes as continued threats of attacks by Palestinian militants.[17]

Definitions

According to Yael Berda of Jerusalem's Hebrew University, the Israeli permit regime is one of three elements underpinning Israel's military management of the occupied population through intelligence, economic control and racial profiling.[10] Berda defines the "permit regime" as the "bureaucratic apparatus of the occupation modeled around that which developed in the West Bank between the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993 through the early 2000s".[1] Cheryl Rubenberg argued that the permit system was the most effective instrument in what other scholars have called Israel's techniques of "suspended violence".[c]

Neve Gordon of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev writes that the permit regime is both the "scaffolding for many other forms of control" while also forming a part of the "infrastructure of control" of the Israeli occupation.[18] Aeyal Gross of Tel Aviv University defines the permit regime as "a legal regime relating to freedom of movement".[19] He writes that the regime allows Israel to further control the lives of Palestinians in line with a goal of "frictionless control" that the IDF has pursued.[20]

Ariella Azoulay and Adi Ophir write that the system itself serves as a link between the security services and the civil authorities as any permit approval requires the consent of security agents within administrative offices.[21] They write that while permits themselves have a long history as a bureaucratic device, that the system "acquired a life and logic of its own in the Occupied Territories".[22]

History

The permit regime began to be implemented before the end of hostilities in the 1967 Six-Day War.[23] Permits would be required for a wide range of activities, and Gordon states that as a whole "the permit regime operated to shape practically every aspect of Palestinian life".[5] Within ten days of the end of the war a military order was issued that required a permit to conduct any business transaction that involved land or property. That same day an order was declared that required Palestinians to hold a permit to possess any foreign currency, with violations punishable by up to five years imprisonment. Permits would be required to install any water device, or to perform electrical work, including connecting a generator. In order to transport any plant or commodity in to or out of the Palestinian territories, a permit was required. Any form of transportation, including tractors and donkey carts, would require a permit to operate.[24] Military order 101 issued 2 months into the occupation in that year criminalized any "procession, gathering, or rally" organized without first obtaining a permit from a military commander, A "rally" was defined as any assembly of ten or more persons that might address either a political matter or anything else that might be interpreted as having the purpose of "incitement". "Incitement" was defined as attempting to influence public opinion in a way that was liable to disturb public peace or order.[25]

In 1968, Israel issued the "Entry to Israel Directive" which required all people entering Israel to possess a valid permit and gave authority for granting those permits to the regional military commander. This directive had no practical effect at the time as Israel had as a policy allowed travel between the newly occupied Palestinian territories of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank to and from Israel.[26] In 1972, Israel issued general exit permits for all residents of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip to enter Israel and East Jerusalem between the hours of 5 AM and 1 AM, formalizing what had been an informal open-border policy between Israel and the Palestinian territories.[27][28]

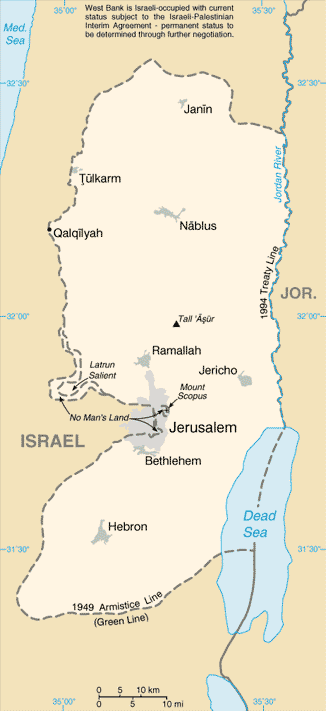

Until the First Intifada or "uprising" in 1987, over 100,000 Palestinians freely commuted into Israel on a daily basis, in cars with West Bank plates, without serious obstacles. Restrictions only applied to those convicted of security offenses.[29] With the uprising, the Israeli army placed greater restrictions on Palestinian movement and imposed security measures such as curfews, closures and the marking of ID cards as either green for those denied entry into Israel, or red for the rest of the population. In 1991 during the Gulf War the general exit permit was revoked and replaced by a system of individual permits designed to "filter out Palestinian movement under [the] security pretext in Israel."[3] The interim Oslo Accords left Israel with partial or full control over 83% of the West Bank and, according to Rashid Khalidi, concomitantly, Israel proceeded to tighten restrictions of what he calls its 'matrix of control, by developing a substantially new system, an intricate "web of procedures" including the "all-encompassing permit system", which suffocated Palestinian movement in the territories.[29]

After the breakdown of negotiations at the 2000 Camp David Summit and the outbreak of the Second Intifada, the IDF imposed a total closure on the occupied territories and made the permit system more stringent in order to protect both its perceived security interests and civilians from armed confrontation with Palestinian militants.[30] After initial attempts to repress the uprising failed, the Israeli West Bank barrier was constructed beyond the Green Line. This was accompanied by another increase in the types of access permits governing Palestinian movements.[31] The system of permits, checkpoints and other measures did prove helpful in ending the Second Intifada, but some, even Israel commanders, argue that the frustrations caused by such restrictive policies could prove conducive to fostering the very terrorism they seek to put down.[d]

Under Israeli military rule, nearly every aspect of everyday Palestinian life was subjected to pervasive military regulations, calculated to the number of 1,300 by 1996, from planting trees and importing books to house extensions.[32] In the first two decades of occupation Palestinians were required to apply to the military authorities for permits and licenses for a number of things such as a driver's license, a telephone, trademark and birth registration, and a good conduct certificate which was indispensable to obtain entry into many branches of professions and to workplaces, with putative security considerations determining the decision, which was delivered by an oral communication. The vital source of information on security risks came from the Israeli Security Agency Shin Bet which was found to have been regularly misleading the courts for 16 years.[33][34] Obtaining such permits has been described as a via dolorosa for the Palestinians seeking them.[35] In 2004, only 0.14% of West Bankers (3,412 out of 2.3 million)[36] had valid permits to travel through West Bank checkpoints, while throughout the whole of 2004 only 2.45% of West Bank inhabitants held any kind of permit at all.[36] Military order 101 denied West Bankers the right to purchase from abroad (including from Israel) any form of printed matter such as books, posters, photographs, and even paintings unless prior authorization had been obtained from the military.[37] Prohibitions also affected dress codes by disallowing certain colour combinations in clothing or refusing to cover the sewage in the Negev detention centre of Ansar 111[38] where a significant numbers of Palestinians have served time.

According to the Israel NGO HaMoked, any tourist from around the world or any Israeli can travel through the Seam Zone but access is forbidden to local Palestinians (roughly 50.000 Palestinians in 38 localities, according to 2012 figures)[39] unless they manage to obtain from the Israeli military authorities any one of 13 permits, depending on their needs.[40] These are classified as follows:

Each type of permit has special requisites, and they are all temporary. Technically, a permit of this kind may cover two years, but most have to be renewed every three months.[43]

Medical treatment in Israel or Palestinian hospitals in East Jerusalem involves obtaining three different permits, depending on whether the person is a patient, an escort, a doctor, or visitors to the hospitalized patient.[6] On the occasion of funerals and weddings, first- or second-degree relatives in the West Bank and Gaza are allowed to apply for the necessary travel permits. Palestinian children require a special permit to attend school in East Jerusalem. A special permit is required if a Palestinian is employed in churches in Israel.[44] In 2016 of 291 Gazan Palestinians requesting a permit to travel on the occasion of a death in the family/clan, permission was accorded to 105, and rejected for 68, while the remaining cases were pending. Of 803 seeking a permit to attend a conference, 84 were given a permit, and 133 refused. Of 148 petitions by Gaza Christians to visit holy sites outside the Strip, none were given, and none rejected. In all cases, the petition was left pending.[45]

Study permits

Students from Gaza trying to obtain study permits for advanced educational institutions in the West Bank, such as Bir Zeit University, faced major difficulties, even if the permits were granted, in completing their degrees. In the 1990s, such permits, to travel and reside in the West Bank, were valid for three months, after which they had to be renewed. On average a Gaza student spent 15 hours in line to obtain a renewal for the fourth month of each semester. If the permit was cancelled, the student was obliged to restart. One condition placed on getting a permit was that the Gazan youths sign a statement in support of political negotiations. No reasons were ever forthcoming as to why many students had their permits cancelled.[71]