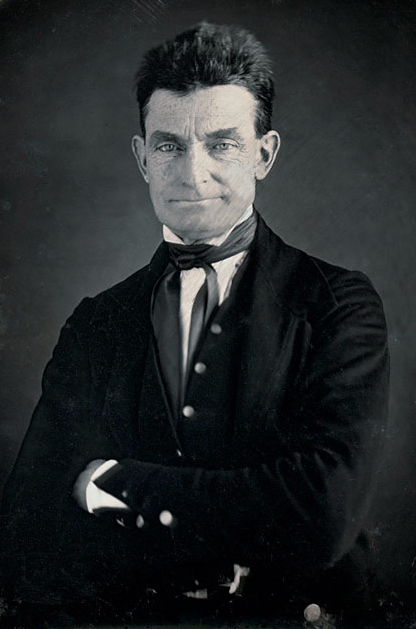

John Brown (abolitionist)

John Brown (May 9, 1800 – December 2, 1859) was a prominent leader in the American abolitionist movement in the decades preceding the Civil War. First reaching national prominence in the 1850s for his radical abolitionism and fighting in Bleeding Kansas, Brown was captured, tried, and executed by the Commonwealth of Virginia for a raid and incitement of a slave rebellion at Harpers Ferry in 1859.

John Brown

May 9, 1800

December 2, 1859 (aged 59)

- Statues in Kansas City, Kansas, and North Elba, New York; Tragic Prelude, mural in the Kansas State Capitol; John Brown Farm State Historic Site, North Elba, New York; John Brown Museum and John Brown Historic Park, Osawatomie, Kansas; Museum and Statue, Akron, Ohio; John Brown Tannery Site, Guys Mills, Pennsylvania

Involvement in Bleeding Kansas; Raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia.

Treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia; murder; inciting slave insurrection

Owen Brown (father)

An evangelical Christian of strong religious convictions, Brown was profoundly influenced by the Puritan faith of his upbringing.[1][2] He believed that he was "an instrument of God,"[3] raised to strike the "death blow" to American slavery, a "sacred obligation."[4] Brown was the leading exponent of violence in the American abolitionist movement,[5] believing it was necessary to end American slavery after decades of peaceful efforts had failed.[6][7] Brown said that in working to free the enslaved, he was following Christian ethics, including the Golden Rule,[8] and the Declaration of Independence, which states that "all men are created equal."[9] He stated that in his view, these two principles "meant the same thing."[10]

Brown first gained national attention when he led anti-slavery volunteers and his sons during the Bleeding Kansas crisis of the late 1850s, a state-level civil war over whether Kansas would enter the Union as a slave state or a free state. He was dissatisfied with abolitionist pacifism, saying of pacifists, "These men are all talk. What we need is action – action!" In May 1856, Brown and his sons killed five supporters of slavery in the Pottawatomie massacre, a response to the sacking of Lawrence by pro-slavery forces. Brown then commanded anti-slavery forces at the Battle of Black Jack and the Battle of Osawatomie.

In October 1859, Brown led a raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (which became West Virginia), intending to start a slave liberation movement that would spread south; he had prepared a Provisional Constitution for the revised, slavery-free United States that he hoped to bring about. He seized the armory, but seven people were killed and ten or more were injured. Brown intended to arm slaves with weapons from the armory, but only a few slaves joined his revolt. Those of Brown's men who had not fled were killed or captured by local militia and U.S. Marines, the latter led by Robert E. Lee. Brown was tried for treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia, the murder of five men, and inciting a slave insurrection. He was found guilty of all charges and was hanged on December 2, 1859, the first person executed for treason against a U.S. state in the history of the United States.[11][12]

The Harpers Ferry raid and Brown's trial, both covered extensively in national newspapers, escalated tensions that in the next year led to the South's long-threatened secession and the American Civil War. Southerners feared that others would soon follow in Brown's footsteps, encouraging and arming slave rebellions. He was a hero and icon in the North. Union soldiers marched to the new song "John Brown's Body" that portrayed him as a heroic martyr. Brown has been variously described as a heroic martyr and visionary, and as a madman and terrorist.[13][14][15]

Influences

The connection between John Brown's life and many of the slave uprisings in the Caribbean was clear from the outset. Brown was born during the period of the Haitian Revolution, which saw Haitian slaves revolting against the French. The role the revolution played in helping formulate Brown's abolitionist views directly is not clear; however, the revolution had an obvious effect on the general view toward slavery in the northern United States, and in the Southern states, it was a warning of horror (as they viewed it) possibly to come. As W. E. B. Du Bois notes, the involvement of slaves in the American Revolutions, and the "upheaval in Hayti, and the new enthusiasm for human rights, led to a wave of emancipation which started in Vermont during the Revolution and swept through New England and Pennsylvania, ending finally in New York and New Jersey".[271]

The 1839 slave insurrection aboard the Spanish ship La Amistad, off the coast of Cuba, provides a poignant example of John Brown's support and appeal toward Caribbean slave revolts. On La Amistad, Joseph Cinqué and approximately 50 other slaves captured the ship, slated to transport them from Havana to Puerto Príncipe, Cuba, in July 1839, and attempted to return to Africa. However, through trickery, the ship ended up in the United States, where Cinque and his men stood trial. Ultimately, the courts acquitted the men because at the time, the international slave trade was illegal in the United States.[272] According to Brown's daughter, "Turner and Cinque stood first in esteem" among Brown's black heroes. Furthermore, she noted Brown's "admiration of Cinques' character and management in carrying his points with so little bloodshed!"[273] In 1850, Brown would refer affectionately to the revolt, in saying "Nothing so charms the American people as personal bravery. Witness the case of Cinques, of everlasting memory, on board the Amistad."[274]

The specific knowledge John Brown gained from the tactics employed in the Haitian Revolution, and other Caribbean revolts, was of paramount importance when Brown turned his sights to the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. As Brown's cohort Richard Realf explained to a committee of the 36th Congress, "he had posted himself in relation to the wars of Toussaint L'Ouverture;[275] he had become thoroughly acquainted with the wars in Hayti and the islands round about."[276] By studying the slave revolts of the Caribbean region, Brown learned a great deal about how to properly conduct guerilla warfare. A key element to the prolonged success of this warfare was the establishment of maroon communities, which are essentially colonies of runaway slaves. As a contemporary article notes, Brown would use these establishments to "retreat from and evade attacks he could not overcome. He would maintain and prolong a guerilla war, of which ... Haiti afforded" an example.[277]

The idea of creating maroon communities was the impetus for the creation of John Brown's "Provisional Constitution and Ordinances for the People of the United States", which helped to detail how such communities would be governed. However, the idea of maroon colonies of slaves is not an idea exclusive to the Caribbean region. In fact, maroon communities riddled the southern United States between the mid-1600s and 1864, especially in the Great Dismal Swamp region of Virginia and North Carolina. Similar to the Haitian Revolution, the Seminole Wars, fought in modern-day Florida, saw the involvement of maroon communities, which although outnumbered by native allies were more effective fighters.[277]

Although the maroon colonies of North America undoubtedly had an effect on John Brown's plan, their impact paled in comparison to that of the maroon communities in places like Haiti, Jamaica, and Surinam. Accounts by Brown's friends and cohorts prove this idea. Richard Realf, a cohort of Brown in Kansas, noted that Brown not only studied the slave revolts in the Caribbean, but focused more specifically on the maroons of Jamaica and those involved in Haiti's liberation.[278] Brown's friend Richard Hinton similarly noted that Brown knew "by heart" the occurrences in Jamaica and Haiti.[279] Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a cohort of Brown's and a member of the Secret Six, stated that Brown's plan involved getting "together bands and families of fugitive slaves" and "establish them permanently in those [mountain] fastnesses, like the Maroons of Jamaica and Surinam".[280]

Archival material

The indictments, summons, sentences, bills of exception, and similar documents for Brown and his raiders are held by the Jefferson County Circuit Clerk, and have been digitized by West Virginia Archives and History.[340] Two separate collections of relevant letters were published. The first is the messages, mostly telegrams, sent and received by Governor Wise.[341] The Senate of Maryland published the many internal telegrams of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.[184]

Much material is missing. The order book, which had the minutes of John Brown's trial,[342] was evidently possessed by Brown's judge Richard Parker in 1888.[343] As of 2022, its location is unknown. Among the missing material used at his trial as evidence of sedition were bundles of printed copies of his Provisional Constitution, prepared for the "state" Brown intended to set up in the Appalachian Mountains. Even less known is Brown's "Declaration of Liberty", imitating the Declaration of Independence.[344]

According to Prosecutor Andrew Hunter,