Abolitionism in the United States

In the United States, abolitionism, the movement that sought to end slavery in the country, was active from the colonial era until the American Civil War, the end of which brought about the abolition of American slavery, except as punishment for a crime, through the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution (ratified 1865).

Not to be confused with Prohibition in the United States.

The anti-slavery movement originated during the Age of Enlightenment, focused on ending the trans-Atlantic slave trade. In Colonial America, a few German Quakers issued the 1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery, which marked the beginning of the American abolitionist movement. Before the Revolutionary War, evangelical colonists were the primary advocates for the opposition to slavery and the slave trade, doing so on the basis of humanitarian ethics. Still, others such as James Oglethorpe, the founder of the colony of Georgia, also retained political motivations for the removal of slavery. Prohibiting slavery through the 1735 Georgia Experiment in part to prevent Spanish partnership with Georgia's runaway slaves, Oglethorpe eventually revoked the act in 1750 after the Spanish's defeat in the Battle of Bloody Marsh eight years prior.[2]

During the Revolutionary era, all states abolished the international slave trade, but South Carolina reversed its decision. Between the Revolutionary War and 1804, laws, constitutions, or court decisions in each of the Northern states provided for the gradual or immediate abolition of slavery.[a] No Southern state adopted similar policies. In 1807, Congress made the importation of slaves a crime, effective January 1, 1808, which was as soon as Article I, section 9 of the Constitution allowed. A small but dedicated group, under leaders such as William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass, agitated for abolition in the mid-19th century. John Brown became an advocate and militia leader in attempting to end slavery by force of arms. In the Civil War, immediate emancipation became a war goal for the Union in 1861 and was fully achieved in 1865.

The Constitution and ending slavery[edit]

The Republican strategy of using the Constitution[edit]

Two diametrically opposed anti-slavery positions emerged regarding the United States Constitution. The Garrisonians emphasized that the document permitted and protected slavery and was therefore "an agreement with hell" that had to be rejected in favor of immediate emancipation. The mainstream anti-slavery position adopted by the new Republican party argued that the Constitution could and should be used to eventually end slavery. They assumed that the Constitution gave the government no authority to abolish slavery directly. However, there were multiple tactics available to support the long-term strategy of using the Constitution as a battering ram against the peculiar institution. First Congress could block the admission of any new slave states. That would steadily move the balance of power in Congress and the Electoral College in favor of freedom. Congress could abolish slavery in the District of Columbia and the territories. Congress could use the Commerce Clause[85] to end the interstate slave trade, thereby crippling the steady movement of slavery from the southeast to the southwest. Congress could recognize free blacks as full citizens and insist on due process rights to protect fugitive slaves from being captured and returned to bondage. Finally, the government could use patronage powers to promote the anti-slavery cause across the country, especially in the border states. Pro-slavery elements considered the Republican strategy to be much more dangerous to their cause than radical abolitionism. Lincoln's election was met by secession. Indeed, the Republican strategy mapped the "crooked path to abolition" that prevailed during the Civil War.[86][87]

Events leading to emancipation[edit]

In the 1850s, the slave trade remained legal in all 16 states of the American South. While slavery was fading away in the cities and border states, it remained strong in plantation areas that grew cash crops such as cotton, sugar, rice, tobacco or hemp. By the 1860 United States Census, the slave population in the United States had grown to four million.[88] American abolitionism, after Nat Turner's revolt ended its discussion in the South, was based in the North, and white Southerners alleged it fostered slave rebellion.

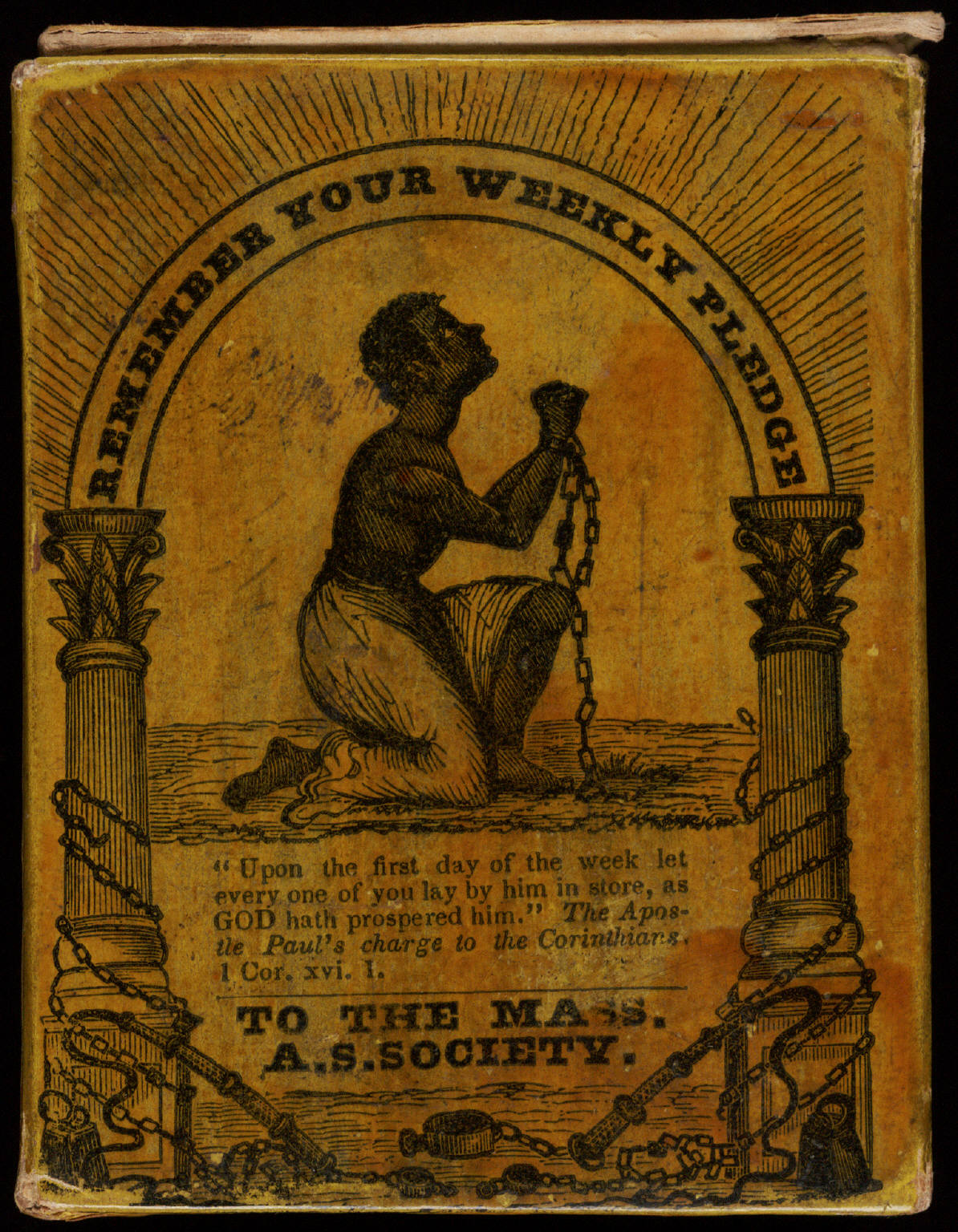

The white abolitionist movement in the North was led by social reformers, especially William Lloyd Garrison, founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society, and writers such as John Greenleaf Whittier and Harriet Beecher Stowe. Black activists included former slaves such as Frederick Douglass, and free blacks such as the brothers Charles Henry Langston and John Mercer Langston, who helped to found the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society.[89][c]

Some abolitionists said that slavery was criminal and a sin; they also criticized slave owners for using black women as concubines and taking sexual advantage of them.[92]

Abolitionist viewpoints[edit]

Religion and morality[edit]

The Second Great Awakening of the 1820s and 1830s in religion inspired groups that undertook many types of social reform. For some that included the immediate abolition of slavery as they considered it sinful to hold slaves as well as to tolerate slavery. Opposition to slavery, for example, was one of the works of piety of the Methodist Churches, which were established by John Wesley.[133] "Abolitionist" had several meanings at the time. The followers of William Lloyd Garrison, including Wendell Phillips and Frederick Douglass, demanded the "immediate abolition of slavery", hence the name, also called "immediatism". A more pragmatic group of abolitionists, such as Theodore Weld and Arthur Tappan, wanted immediate action, but were willing to support a program of gradual emancipation, with a long intermediate stage.

"Anti-slavery men", such as John Quincy Adams, did not call slavery a sin. They called it an evil feature of society as a whole. They did what they could to limit slavery and end it where possible, but were not part of any abolitionist group. For example, in 1841, John Quincy Adams represented the Amistad African slaves in the Supreme Court of the United States and argued that they should be set free.[134] In the last years before the war, "anti-slavery" could refer to the Northern majority, such as Abraham Lincoln, who opposed expansion of slavery or its influence, as by the Kansas–Nebraska Act or the Fugitive Slave Act. Many Southerners called all these abolitionists, without distinguishing them from the Garrisonians.

Historian James Stewart (1976) explains the abolitionists' deep beliefs: "All people were equal in God's sight; the souls of black folks were as valuable as those of whites; for one of God's children to enslave another was a violation of the Higher Law, even if it was sanctioned by the Constitution."[60]

Anti-abolitionist viewpoints[edit]

Anti-abolitionism in the North[edit]

It is easy to overstate the support for abolitionism in the North. "From Maine to Missouri, from the Atlantic to the Gulf, crowds gathered to hear mayors and aldermen, bankers and lawyers, ministers and priests denounce the abolitionists as amalgamationists, dupes, fanatics, foreign agents, and incendiaries."[159] The whole abolitionist movement, the cadre of anti-slavery lecturers, was primarily focused on the North: convincing Northerners that slavery should be immediately abolished, and freed slaves given rights.

A majority of white Southerners, though by no means all, supported slavery; there was a growing feeling in favor of emancipation in North Carolina,[160] Maryland, Virginia, and Kentucky, until the panic resulting from Nat Turner's 1831 revolt put an end to it.[161]: 14 [162]: 111 But only a minority in the North supported abolition, seen as an extreme, "radical" measure. (See Radical Republicans.) Horace Greeley remarked in 1854 that he had "never been able to discover any strong, pervading, over-ruling Anti Slavery sentiment in the Free States."[163] Free blacks were subject in the North as well as in the South to conditions almost inconceivable today (2019).[164]

Although the picture is neither uniform nor static, in general free blacks in the North were not citizens and could neither vote nor hold public office. They could not give testimony in court and their word was never taken against a white man's word, as a result of which white crimes against blacks were rarely punished.[165]: 154–155 Black children could not study in the public schools, even though Black taxpayers helped support them,[90]: 154 and there were only a handful of schools for Black students, like the African Free School in New York, the Abiel Smith School in Boston, and the Watkins Academy for Negro Youth in Baltimore. When schools for negroes were set up in Ohio in the 1830s, the teacher of one slept in it every night "for fear whites would burn it", and at another, "a vigilance committee threatened to tar and feather [the teacher] and ride her on a rail if she did not leave".[70]: 245–246 "Black education was a dangerous pursuit for teachers."[166]

Most colleges would not admit blacks. (Oberlin Collegiate Institute was the first college that survived to admit them by policy; the Oneida Institute was a short-lived predecessor.) In wages, housing, access to services, and transportation, separate but equal or Jim Crow treatment would have been a great improvement. The proposal to create the country's first college for negros, in New Haven, Connecticut, got such strong local opposition (New Haven Excitement) that it was quickly abandoned.[167][168] Schools in which blacks and whites studied together in Canaan, New Hampshire,[169] and Canterbury, Connecticut,[170] were physically destroyed by mobs.

Southern actions against white abolitionists took legal channels: Amos Dresser was tried, convicted, and publicly whipped in Knoxville, and Reuben Crandall, Prudence Crandall's younger brother, was arrested in Washington D.C., and was found innocent, although he died soon of tuberculosis he contracted in jail. (The prosecutor was Francis Scott Key.) In Savannah, Georgia, the mayor and alderman protected an abolitionist visitor from a mob.[171]