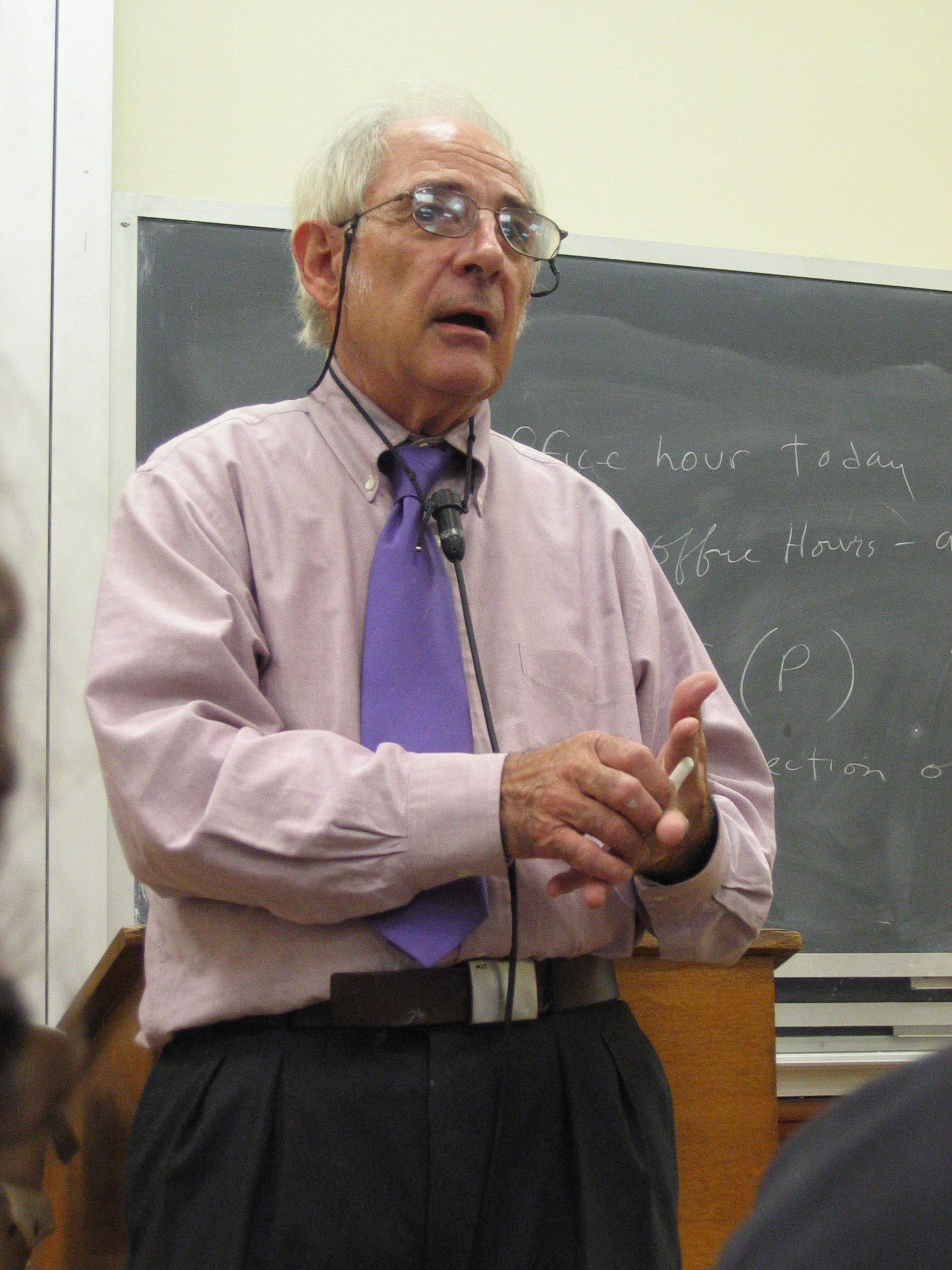

John Searle

John Rogers Searle (American English pronunciation: /sɜːrl/; born July 31, 1932)[4] is an American philosopher widely noted for contributions to the philosophy of language, philosophy of mind, and social philosophy. He began teaching at UC Berkeley in 1959, and was Willis S. and Marion Slusser Professor Emeritus of the Philosophy of Mind and Language and Professor of the Graduate School at the University of California, Berkeley, until June 2019, when his status as professor emeritus was revoked because he was found to have violated the university's sexual harassment policies.[5]

This article is about the American philosopher. For the American businessman and philanthropist, see John Gideon Searle. For the American minister and educator, see John Preston Searle. For the Australian educator, see John W. Searle. For other people, see John Serle (disambiguation).

John Rogers Searle

Dagmar Searle[3]

As an undergraduate at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Searle was secretary of "Students against Joseph McCarthy". He received all his university degrees, BA, MA, and DPhil, from the University of Oxford, where he held his first faculty positions. Later, at UC Berkeley, he became the first tenured professor to join the 1964–1965 Free Speech Movement. In the late 1980s, Searle challenged the restrictions of Berkeley's 1980 rent stabilization ordinance. Following what came to be known as the California Supreme Court's "Searle Decision" of 1990, Berkeley changed its rent control policy, leading to large rent increases between 1991 and 1994.

In 2000, Searle received the Jean Nicod Prize;[6] in 2004, the National Humanities Medal;[7] and in 2006, the Mind & Brain Prize. In 2010 he was elected to the American Philosophical Society.[8] Searle's early work on speech acts, influenced by J.L. Austin and Ludwig Wittgenstein, helped establish his reputation. His notable concepts include the "Chinese room" argument against "strong" artificial intelligence.

Philosophical work[edit]

Speech acts[edit]

Searle's early work, which did much to establish his reputation, was on speech acts. He attempted to synthesize ideas from many colleagues – including J.L. Austin (the "illocutionary act", from How To Do Things with Words), Ludwig Wittgenstein and G.C.J. Midgley (the distinction between regulative and constitutive rules) – with his own thesis that such acts are constituted by the rules of language. He also drew on the work of Paul Grice (the analysis of meaning as an attempt at being understood), Hare and Stenius (the distinction, concerning meaning, between illocutionary force and propositional content), P.F. Strawson, John Rawls and William Alston, who maintained that sentence meaning consists in sets of regulative rules requiring the speaker to perform the illocutionary act indicated by the sentence and that such acts involve the utterance of a sentence which (a) indicates that one performs the act; (b) means what one says; and (c) addresses an audience in the vicinity.

In his 1969 book Speech Acts, Searle sets out to combine all these elements to give his account of illocutionary acts. There he provides an analysis of what he considers the prototypical illocutionary act of promising and offers sets of semantical rules intended to represent the linguistic meaning of devices indicating further illocutionary act types. Among concepts presented in the book is the distinction between the "illocutionary force" and the "propositional content" of an utterance. Searle does not precisely define the former as such, but rather introduces several possible illocutionary forces by example. According to Searle, the sentences...