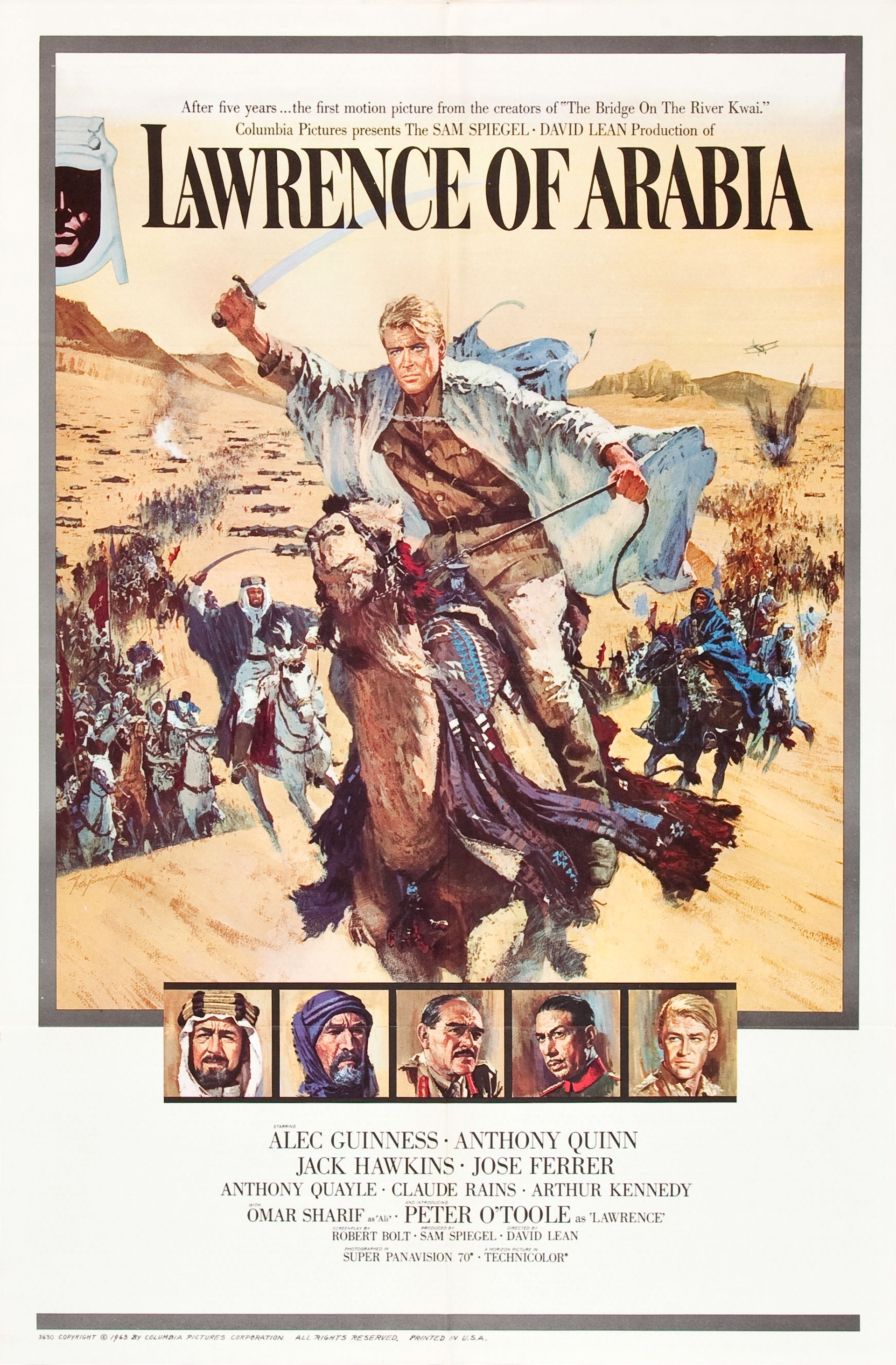

Lawrence of Arabia (film)

Lawrence of Arabia is a 1962 epic biographical adventure drama film based on the life of T. E. Lawrence and his 1926 book Seven Pillars of Wisdom (also known as Revolt in the Desert[6]). It was directed by David Lean and produced by Sam Spiegel through his British company Horizon Pictures and distributed by Columbia Pictures. The film stars Peter O'Toole as Lawrence with Alec Guinness playing Prince Faisal. The film also stars Jack Hawkins, Anthony Quinn, Omar Sharif, Anthony Quayle, Claude Rains and Arthur Kennedy. The screenplay was written by Robert Bolt and Michael Wilson.

The film depicts Lawrence's experiences in the Ottoman provinces of Hejaz and Greater Syria during the First World War, in particular his attacks on Aqaba and Damascus and his involvement in the Arab National Council. Its themes include Lawrence's emotional struggles with the violence inherent in war, his identity and his divided allegiance between his native Britain and his new-found comrades within the Arabian desert tribes.

The film was nominated for ten Oscars at the 35th Academy Awards in 1963, winning seven including Best Picture and Best Director. It also won the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama and the BAFTA Awards for Best Film and Outstanding British Film. The dramatic score by Maurice Jarre and the Super Panavision 70 cinematography by Freddie Young also won praise from critics.

Lawrence of Arabia is widely regarded as one of the greatest films ever made. In 1991, it was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.[7][8] In 1998, the American Film Institute placed it fifth on their 100 Years...100 Movies list of the greatest American films and it ranked seventh on their 2007 updated list. In 1999, the British Film Institute named the film the third-greatest British film. In 2004, it was voted the best British film in The Sunday Telegraph poll of Britain's leading filmmakers.

The crew consisted of over 200 people. Including cast and extras, over 1,000 people worked on the film.[19] Members of the crew portrayed minor characters. First assistant director Roy Stevens played the truck driver who transports Lawrence and Farraj to the Cairo HQ at the end of Act I; the sergeant who stops Lawrence and Farraj ("Where do you think you're going to, Mustapha?") is construction assistant Fred Bennett and screenwriter Robert Bolt has a wordless cameo as one of the officers watching Allenby and Lawrence confer in the courtyard (he is smoking a pipe).[20] Steve Birtles, the film's gaffer, played the motorcyclist at the Suez Canal; Lean is rumoured to have provided the cyclist's voice shouting "Who are you?" Continuity supervisor Barbara Cole appeared as one of the nurses in the Damascus hospital scene.

Production[edit]

Pre-production[edit]

Previous films about T. E. Lawrence had been planned but had not been made. In the 1940s, Alexander Korda was interested in filming The Seven Pillars of Wisdom with Laurence Olivier, Leslie Howard, or Robert Donat as Lawrence, but had to pull out owing to financial difficulties. David Lean had been approached to direct a 1952 version for the Rank Organisation, but the project fell through.[40] At the same time as pre-production of the film, Terence Rattigan was developing his play Ross which centred primarily on Lawrence's alleged homosexuality. Ross had begun as a screenplay, but was re-written for the stage when the film project fell through. Sam Spiegel grew furious and attempted to have the play suppressed, which helped to gain publicity for the film.[41] Dirk Bogarde had accepted the role in Ross; he described the cancellation of the project as "my bitterest disappointment". Alec Guinness played the role on stage.[42]

Lean and Sam Spiegel had worked together on The Bridge on the River Kwai and decided to collaborate again. For a time, Lean was interested in a biopic of Gandhi, with Alec Guinness to play the title role and Emeric Pressburger writing the screenplay. He eventually lost interest in the project, despite extensive pre-production work, including location scouting in India and a meeting with Jawaharlal Nehru.[43] Lean then returned his attention to T. E. Lawrence. Columbia Pictures had an interest in a Lawrence project dating back to the early '50s, and the project got underway when Spiegel convinced a reluctant A. W. Lawrence to sell the rights to Seven Pillars of Wisdom for £22,500.[44]

Michael Wilson wrote the original draft of the screenplay. Lean was dissatisfied with Wilson's work, primarily because his treatment focused on the historical and political aspects of the Arab Revolt. Lean hired Robert Bolt to re-write the script to make it a character study of Lawrence. Many of the characters and scenes are Wilson's invention, but virtually all of the dialogue in the finished film was written by Bolt.[45]

Lean reportedly watched John Ford's 1956 film The Searchers to help him develop ideas as to how to shoot the film. Several scenes directly recall Ford's film, most notably Ali's entrance at the well and the composition of many of the desert scenes and the dramatic exit from Wadi Rum. Lean biographer Kevin Brownlow noted a physical similarity between Wadi Rum and Ford's Monument Valley.[46]

In an interview with The Washington Post in 1989, Lean said that Lawrence and Ali were written as being in a gay relationship. When asked about whether the film was "pervasively homoerotic", Lean responded:

Release[edit]

Theatrical run[edit]

The film premiered at the Odeon Leicester Square in London on 10 December 1962 and was released in the United States on 16 December 1962.

Jordan banned the film for what was felt to be a disrespectful portrayal of Arab culture.[10] Egypt, Omar Sharif's home country, was the only Arab nation to give the film a wide release, where it became a success through the endorsement of President Gamal Abdel Nasser, who appreciated the film's depiction of Arab nationalism.

Reception[edit]

Critical reaction[edit]

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called the film "vast, awe-inspiring, beautiful with ever-changing hues, exhausting and barren of humanity". He further wrote Lawrence's characterisation was lost within the spectacle, writing the film "reduces a legendary figure to conventional movie-hero size amidst magnificent and exotic scenery but a conventional lot of action-film cliches".[87] Similarly, Variety wrote that the film was "a sweepingly produced, directed and lensed job. Authentic desert locations, a stellar cast and an intriguing subject combine to put this into the blockbuster league." However, it later noted Bolt's screenplay "does not tell the audience anything much new about Lawrence of Arabia nor does it offer any opinion or theory about the character of this man or the motivation for his actions".[88] Philip K. Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times wrote: "It is also one of the most magnificent pictures, if not the magnificent, and one of the most exasperating ... The awesome majesty of the landscapes in Jordan and elsewhere, the mass movements of Bedouins and British and Turks with, of course, the ever-present camels, sweep against the eye long after one has lost the ability to exclaim in astonishment over them. And all this is Technicolor and Super Panavision 70, the finest process, under F. A. Young as director of photography. Maurice Jarre composed a score to match."[89]

A review in Time magazine felt that while Lawrence of Arabia "falls far short of Kwai in dramatic impact, it nevertheless presents a vivid and intelligent spectacle". It further praised O'Toole's performance, writing he "continually dominates the screen, and he dominates it with professional skill, Irish charm and smashing good looks".[90] Chicago Tribune wrote the photography was "no less than superb" and felt the script "is taut and expressive and the musical score deftly attuned to the tale. Director David Lean has molded his massive material with skill, but personally I felt the film was too long, the running time is 221 minutes, or 20 minutes short of 4 hours and in the latter part, unnecessarily bloody."[91] A review in Newsweek praised the film as "an admirably seriously film ... The size, the scope, the fantastical scale of his personality and his achievement is triumphantly there." It also praised the ensemble cast as "all as good as they ought to be. And Peter O'Toole is not only good; he is an unnerving look-alike of the real Lawrence. He is reliably unreliable, steadily mercurial."[92]

In 1998, the American Film Institute (AFI) ranked Lawrence of Arabia in fifth place in their list of 100 Years...100 Movies. In 2006, AFI ranked the film #30 on its list of most inspiring movies.[93] In 2007, it was ranked in seventh place in their updated list and listed as the first of the greatest American films of the "epic" genre.[94] In 1991, the film was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry.[8] In 1999, the film placed third in the British Film Institute's poll of the best British films of the 20th century. In 2001, the magazine Total Film called it "as shockingly beautiful and hugely intelligent as any film ever made" and "faultless".[95]

It was ranked in the top ten films of all time in the 2002 Sight and Sound directors' poll.[96] In 2004, it was voted the best British film of all time by over 200 respondents in The Sunday Telegraph poll of Britain's leading filmmakers.[97] O'Toole's performance is often considered one of the greatest in cinema history, topping lists from Entertainment Weekly and Première. T. E. Lawrence, portrayed by O'Toole, was selected as the tenth-greatest hero in cinema history by the American Film Institute.[98] In 2012, the Motion Picture Editors Guild listed the film as the seventh best-edited of all time based on a survey of its membership.[99] In March 2024, Robbie Collin of The Telegraph ranked Lawrence of Arabia as the greatest biographical film of all time.[100]

Lawrence of Arabia is currently one of the highest-rated films on Metacritic; it holds a perfect 100 rating based on eight reviews.[101] It has a 94% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 133 reviews, with an average rating of 9.30/10. Its critical consensus reads: "The epic of all epics, Lawrence of Arabia cements director David Lean's status in the film-making pantheon with nearly four hours of grand scope, brilliant performances, and beautiful cinematography."[102]

The Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa cited this movie as one of his 100 favourite films.[103]

Legacy[edit]

Its visual style has influenced many directors, including George Lucas, Sam Peckinpah, Stanley Kubrick, Martin Scorsese, Ridley Scott, Brian De Palma, Oliver Stone, Denis Villeneuve, and Steven Spielberg, who called the film a "miracle".[113] Spielberg further considered it his favourite film of all time and the one that inspired him to become a filmmaker,[114] crediting the film, which he saw four times in four successive weeks upon its release, with understanding "It was the first time seeing a movie, I realized there are themes that aren't narrative story themes, there are themes that are character themes, that are personal themes. [...] and I realized there was no going back. It was what I was going to do."[115]

Film director Kathryn Bigelow also considers it one of her favourite films, saying it inspired her to film The Hurt Locker in Jordan.[116] Lawrence of Arabia also inspired numerous other adventure, science fiction and fantasy stories in modern popular culture, including Frank Herbert's Dune franchise, George Lucas's Star Wars franchise, James Cameron's Avatar franchise, Ridley Scott's Prometheus (2012), and George Miller's Mad Max: Fury Road (2015).[117]