Louie Louie

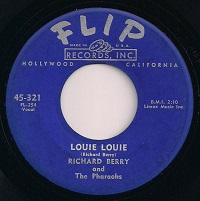

"Louie Louie" is a rhythm and blues song written and composed by American musician Richard Berry in 1955, recorded in 1956, and released in 1957. It is best known for the 1963 hit version by the Kingsmen and has become a standard in pop and rock. The song is based on the tune "El Loco Cha Cha" popularized by bandleader René Touzet and is an example of Afro-Cuban influence on American popular music.

This article is about the song. For the American singer, see Louie Louie (musician). For other uses, see Louie Louie (disambiguation)."Louie Louie"

"Louie Louie" tells, in simple verse–chorus form, the first-person story of a "lovesick sailor's lament to a bartender about wanting to get back home to his girl".[2]

"Louie Louie"

"Maryanne"

1961

1960

2:40 single, 2:32 album

Etiquette ET-1

Richard Berry

"Haunted Castle"

June 1963 (Jerden)

October 1963 (Wand)

April 6, 1963

Northwestern Inc.

2:42 (Jerden), 2:24 (Wand)[78]

Richard Berry

- Ken Chase

- Jerry Dennon

May 1963 (Sandē)

June 1963 (Columbia)

April 1963

Northwestern Inc.

2:38

Sandē 101, Columbia 4-42814

Richard Berry

Roger Hart

November 27, 1964

October 18, 1964

Pye, London

2:57

Pye NEP 24200

Richard Berry

October 1966

1966

2:45 (single), 2:47 (album)

A&M Records 819

Richard Berry

Tommy LiPuma

"Tear Ya Down"

25 August 1978

1978

Wessex, London

2:47

Richard Berry

- Neil Richmond

- Motörhead

"Damaged I"

1981

5:22

Richard Berry

- Spot

- Black Flag

"Louie Louie" has spawned a number of answer songs, sequels, and tributes from the 1960s to the present:

Due to the song's distinctive rhythm and simple structure, it has been used often as a basis for parodies and rewrites. Examples include:

Lyrics controversy and investigations[edit]

As "Louie Louie" began to climb the national charts in late 1963, Jack Ely's "slurry snarl"[424] and "mush-mouthed",[425] "gloriously garbled",[426] "infamously incomprehensible",[427] "legendarily manic",[428] "punk squawk"[44] vocals gave rise to rumors about "dirty lyrics". The Kingsmen initially ignored the rumors, but soon "news networks were filing reports from New Orleans, Florida, Michigan, and elsewhere about an American public nearly hysterical over the possible dangers of this record".[91] The song quickly became "something of a Rorschach test for dirty minds"[429] who "thought they could detect obscene suggestions in the lyric".[430]

In January 1964, Indiana governor Matthew E. Welsh, acting on multiple complaint letters, determined the lyrics to be pornographic because his "ears tingled" when he listened to the record.[431][432] He referred the matter to the FCC and also requested that the Indiana Broadcasters Association advise their member stations to pull the record from their playlists. An initial FCC investigation found the song "unintelligible at any speed".[433]

The National Association of Broadcasters also investigated and deemed it "unintelligible to the average listener", but that "[t]he phonetic qualities of this recording are such that a listener possessing the 'phony' lyrics could imagine them to be genuine."[434] Neither the FCC nor the NAB took any further action.

In response, Max Feirtag of publisher Limax Music offered $1,000 to "anyone finding anything suggestive in the lyrics",[435] and Broadcasting magazine published the actual lyrics as provided by Limax.[436] Scepter/Wand Records commented, "Not in anyone's wildest imagination are the lyrics as presented on the Wand recording suggestive, let alone obscene."[437] Producer Jerry Dennon thanked the governor, saying, "We really owe Governor Welsh a lot. The record already was going great, but since he's stepped in to give us a publicity boost, it's hard to keep up with orders."[438] Billboard noted, "It also seems likely that some shrewd press agentry may also be playing an important role in this teapot tempest."[431]

The following month an outraged parent wrote to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy alleging that the lyrics of "Louie Louie" were obscene, saying, "The lyrics are so filthy that I can-not [sic] enclose them in this letter."[439][440] The Federal Bureau of Investigation investigated the complaint,[441] and looked into the various rumors of "real lyrics" that were circulating among teenagers.[442] In June 1965, the FBI laboratory obtained a copy of the Kingsmen recording and, after 31 months of investigation, concluded that it could not be interpreted[443] and therefore the Bureau could not find that the recording was obscene.[22]

Over the course of the investigation, a "folk legend of modern times that has yet to be bettered for sheer inanity",[44] the FBI interviewed Richard Berry, members of the Kingsmen, members of Paul Revere and the Raiders, and record company executives. The one person they never interviewed was the man who actually sang the words in question, Jack Ely, whose name apparently never came up because he was no longer with the Kingsmen.[442][444][445]

By contrast, in 1964 the Ohio State University student newspaper The Lantern initiated an investigation in response to a growing campus controversy. Working with local radio station WCOL, a letter was sent to Wand Records requesting a copy of the lyrics. The paper printed the lyrics in full, resolving the issue, and resulting in booking the Kingsmen for the fall homecoming entertainment.[446]

In a 1964 interview, Lynn Easton of the Kingsmen said, "We took the words from the original version and recorded them faithfully",[432] and group member Barry Curtis later added, "Richard Berry never wrote dirty lyrics ... you listen and you hear what you want to hear."[19] Richard Berry told Esquire in 1988 that the Kingsmen had sung the song exactly as written[26] and often deflected questions about the lyrics by saying, "If I told you the words, you wouldn't believe me anyway."[447][448]

In a 1991 Dave Marsh interview, Governor Welsh "emphatically denied being a censor", claiming he never banned the record and only suggested that it not be played. Marsh disagreed, saying, "If a record isn't played at the suggestion of the state's chief executive, it has been banned."[449]

A history of the song and its notoriety was published in 1993 by Dave Marsh, including an extensive recounting of the multiple lyrics investigations,[450] but he was unable to obtain permission to publish the song's actual lyrics[451] because the then current owner, Windswept Pacific, wanted people to "continue to fantasize what the words are".[452] Marsh noted that the lyrics controversy "reflected the country's infantile sexuality" and "ensured the song's eternal perpetuation"; he also included multiple versions of the supposed "dirty lyrics".[23] Other authors noted that the song "reap[ed] the benefits that accrue from being pursued by the guardians of public morals"[453] and "[s]uch stupidity helped ensure 'Louie Louie' a long and prosperous life."[454]

The lyrics controversy resurfaced briefly in 2005 when the superintendent of the school system in Benton Harbor, Michigan, refused to let a marching band play the song in a local parade; she later relented.[2]

Cultural impact[edit]

Book[edit]

Music critic Dave Marsh wrote a 245-page book about the song, Louie Louie: The History and Mythology of the World's Most Famous Rock 'n Roll Song, Including the Full Details of Its Torture and Persecution at the Hands of the Kingsmen, J.Edgar Hoover's F.B.I, and a Cast of Millions.[455]

The Who[edit]

The Who were impacted in their early recording career by the riff/rhythm of "Louie Louie", owing to the song's influence on the Kinks, who were also produced by Shel Talmy. Talmy wanted the successful sounds of the Kinks' 1964 hits "You Really Got Me", "All Day and All of the Night", and "Till the End of the Day" to be copied by the Who.[159] As a result, Pete Townshend penned "I Can't Explain", "a desperate copy of The Kinks",[456] released in March 1965. The Who also covered the 1964 Lindsay-Revere sequel "Louie Go Home" in 1965 as "Lubie (Come Back Home)".

In 1979, "Louie Louie" (Kingsmen version) was included on the Quadrophenia soundtrack album, and in 1980 the group performed a brief version in concert at the Los Angeles Sports Arena.[457][458] In his 1993 book, Dave Marsh compared Keith Moon's drumming style to Lynn Easton of the Kingsmen.[459]

"Psyché Rock" and Futurama[edit]

In 1967 French composers Michel Colombier and Pierre Henry, collaborating as Les Yper-Sound, produced a synthesizer and musique concrète work based on the "Louie Louie" riff titled "Psyché Rock".[460] They subsequently worked with choreographer Maurice Béjart on a "Psyché Rock"-based score for the ballet Messe pour le temps présent. The full score with multiple mixes of "Psyché Rock" was released the same year on the album Métamorphose. The album was reissued in 1997 with additional remixes including one by Ken Abyss titled "Psyché Rock (Metal Time Machine Mix)" which, along with the original, "... Christopher Tyng reworked into the theme song for the animated television comedy series Futurama."[461][462][463]

"Louie Louie" marathons[edit]

In the early 1980s, KPFK DJs Art Damage and Chuck Steak began hosting a weekly "Battle of the Louie Louie" contest featuring multiple renditions and listener voting.[15] In 1981, KFJC DJ Jeff "Stretch" Riedle broadcast a full hour of various versions. Soon after, KALX in Berkeley responded and the two stations engaged in a "Louie Louie" marathon battle with each increasing the number of versions played. KFJC's Maximum Louie Louie Marathon topped the competition in August 1983 with 823 versions played over 63 hours, plus in studio performances by Richard Berry and Jack Ely.[464][465]

During a change in format from adult-contemporary to all-oldies in 1997, WXMP in Peoria became "all Louie, all the time," playing nothing but covers of "Louie Louie" for six straight days.[466] Other stations used the same idea to introduce format changes including WWSW (Pittsburgh), KROX (Dallas), WNOR (Norfolk), and WRQN (Toledo).[467][468]

In 2011, KFJC celebrated International Louie Louie Day with a reprise of its 1983 event, featuring multiple "Louie Louie" versions, new music by Richard Berry and appearances by musicians, DJs, and celebrities with "Louie Louie" connections.[469] In April 2015, Orme Radio broadcast the First Italian Louie Louie Marathon, playing 279 versions in 24 hours.[470] In 2023, the city of Portland hosted a 24-hour live marathon to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the Kingsmen version.[471]