Modern dance

Modern dance is a broad genre of western concert or theatrical dance which includes dance styles such as ballet, folk, ethnic, religious, and social dancing; and primarily arose out of Europe and the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was considered to have been developed as a rejection of, or rebellion against, classical ballet, and also a way to express social concerns like socioeconomic and cultural factors.[1][2][3]

For the Pere Ubu album, see The Modern Dance.

In the late 19th century, modern dance artists such as Isadora Duncan, Maud Allan, and Loie Fuller were pioneering new forms and practices in what is now called improvisational or free dance. These dancers disregarded ballet's strict movement vocabulary (the particular, limited set of movements that were considered proper to ballet) and stopped wearing corsets and pointe shoes in the search for greater freedom of movement.[3]

Throughout the 20th century, sociopolitical concerns, major historical events, and the development of other art forms contributed to the continued development of modern dance in the United States and Europe. Moving into the 1960s, new ideas about dance began to emerge as a response to earlier dance forms and to social changes. Eventually, postmodern dance artists would reject the formalism of modern dance, and include elements such as performance art, contact improvisation, release technique, and improvisation.[3][4]

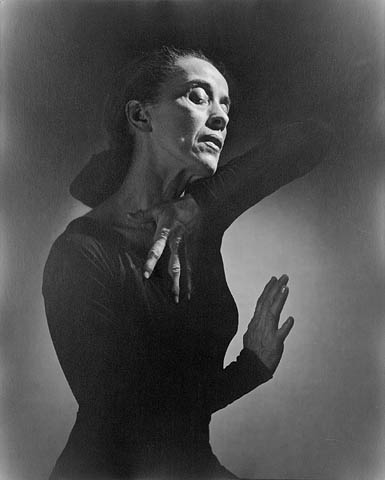

American modern dance can be divided (roughly) into three periods or eras. In the Early Modern period (c. 1880–1923), characterized by the work of Isadora Duncan, Loie Fuller, Ruth St. Denis, Ted Shawn, and Eleanor King, artistic practice changed radically, but clearly distinct modern dance techniques had not yet emerged. In the Central Modern period (c. 1923–1946), choreographers Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Katherine Dunham, Charles Weidman, and Lester Horton sought to develop distinctively American movement styles and vocabularies, and developed clearly defined and recognizable dance training systems. In the Late Modern period (c. 1946–1957), José Limón, Pearl Primus, Merce Cunningham, Talley Beatty, Erick Hawkins, Anna Sokolow, Anna Halprin, and Paul Taylor introduced clear abstractionism and avant-garde movements, and paved the way for postmodern dance.[5]

Modern dance has evolved with each subsequent generation of participating artists. Artistic content has morphed and shifted from one choreographer to another, as have styles and techniques. Artists such as Graham and Horton developed techniques in the Central Modern Period that are still taught worldwide and numerous other types of modern dance exist today.[1][2]

This list illustrates some important teacher-student relationships in modern dance.