Sarah Bernhardt

Sarah Bernhardt (French: [saʁa bɛʁnɑʁt];[note 1] born Henriette-Rosine Bernard; 22 October 1844 – 26 March 1923) was a French stage actress who starred in some of the more popular French plays of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including La Dame aux Camélias by Alexandre Dumas fils, Ruy Blas by Victor Hugo, Fédora and La Tosca by Victorien Sardou, and L'Aiglon by Edmond Rostand. She also played male roles, including Shakespeare's Hamlet. Rostand called her "the queen of the pose and the princess of the gesture", and Hugo praised her "golden voice". She made several theatrical tours around the world, and she was one of the early prominent actresses to make sound recordings and to act in motion pictures.

This article is about the French stage actress. For the American comedienne/actress, see Sandra Bernhard. For the episode of an adventure series, see Sarah Bernhardt (Lucky Luke).

Sarah Bernhardt

She is also linked with the success of artist Alphonse Mucha, whose work she helped to publicize. Mucha became one of the more sought-after artists of this period for his Art Nouveau style.

Bernhardt was one of the early actresses to star in moving pictures. The first projected film was shown by the Lumière brothers at the Grand Café in Paris on 28 December 1895. In 1900, the cameraman who had shot the first films for the Lumière brothers, Clément Maurice, approached Bernhardt and asked her to make a film out of a scene from her stage production of Hamlet. The scene was Prince Hamlet's duel with Laertes, with Bernhardt in the role of Hamlet. Maurice made a phonograph recording at the same time, so the film could be accompanied by sound. The sound of the clashing wooden prop swords was not loud and realistic enough, so Maurice had a stage hand bang pieces of metal together in sync with the sword fight. Maurice's finished two-minute film, Le Duel d'Hamlet, was presented to the public at the 1900 Paris Universal Exposition from 14 April to 12 November 1900 in Paul Decauville's program, Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre. This program contained short films of many other famous French theatre stars of the day.[153] The sound quality on the wax cylinders and the synchronization were very poor, so the system never became a commercial success. Nonetheless, her film is cited as one of the early examples of a sound film.[154]

Eight years later, in 1908, Bernhardt made a second motion picture, La Tosca. This was produced by Le Film d'Art and directed by André Calmettes from the play by Victorien Sardou. The film has been lost. Her next film, with her co-star and lover Lou Tellegen, was La Dame aux Camelias, called "Camille". When she performed on this film, Bernhardt changed both the fashion in which she performed, significantly accelerating the speed of her gestural action.[155] The film was a success in the United States, and in France, the young French artist and later screenwriter Jean Cocteau wrote "What actress can play a lover better than she does in this film? No one!"[156] Bernhardt received $30,000 for her performance.

Shortly afterwards, she made another film of a scene from her play Adrienne Lecouvreur with Tellegen, in the role of Maurice de Saxe. Then, in 1912, the pioneer American producer Adolph Zukor came to London and filmed her performing scenes from her stage play Queen Elizabeth with her lover Tellegen, with Bernhardt in the role of Lord Essex.[157] To make the film more appealing, Zukor had the film print hand-tinted, making it one of the early color films. The Loves of Queen Elizabeth premiered at the Lyceum Theater in New York City on 12 July 1912, and was a financial success; Zukor invested $18,000 in the film and earned $80,000, enabling him to found the Famous Players Film Company, which later became Paramount Pictures.[158] The use of the visual arts–specifically famous c.19 painting–to frame scenes and elaborate narrative action is significant in the work.[155]

Bernhardt was also the subject and star of two documentaries, including Sarah Bernhardt à Belle-Isle (1915), a film about her daily life at home. This was one of the early films by a celebrity inviting us into the home, and it is again significant for the use it makes of contemporary art references in the mis-en-scene of the film.[155] She also made Jeanne Doré in 1916. This was produced by Eclipse and directed by Louis Mercanton and René Hervil from the play by Tristan Bernard. In 1917 she made a film called Mothers of France (Mères Françaises). Produced by Eclipse it was directed by Louis Mercanton and René Hervil with a screenplay by Jean Richepin. As Victoria Duckett explains in her book Seeing Sarah Bernhardt: Performance and Silent Film, this film was a propaganda film shot on the front line with the intent to urge America to join the War.[155]

In the weeks before her death in 1923, she was preparing to make La Voyante, another motion picture from her own home, directed by Sacha Guitry. She told journalists "They're paying me ten thousand francs a day, and plan to film for seven days. Make the calculation. These are American rates, and I don't have to cross the Atlantic! At those rates, I'm ready to appear in any films they make."[159] However, she died just before the filming began.[160]

Bernhardt began painting while she was at the Comédie-Française; because she rarely performed more than twice a week, she wanted a new activity to fill her time. Her paintings were mostly landscapes and seascapes, with many painted at Belle-Île. Her painting teachers were close and lifelong friends Georges Clairin and Louise Abbéma. She exhibited a 2-m-tall canvas, The Young Woman and Death, at the 1878 Paris Salon.[161]

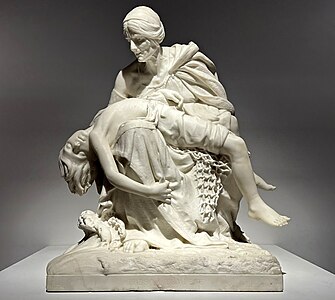

Her passion for sculpture was more serious. Her sculpture teacher was Mathieu-Meusnier, an academic sculptor who specialised in public monuments and sentimental storytelling pieces.[162] She quickly picked up the techniques; she exhibited and sold a high-relief plaque of the death of Ophelia and, for the architect Charles Garnier, she created the allegorical figure of Song for the group Music on the façade of the Opera House of Monte Carlo.[163] She also exhibited a group of figures, called Après la Tempête (After the Storm), at the 1876 Paris Salon, receiving an honourable mention. Bernhardt sold the original work, the molds, and signed plaster miniatures, earning more than 10,000 francs.[163] The original is now displayed in the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C. Fifty works by Bernhardt have been documented, of which 25 are known to still exist.[164] Several of her works were also shown in the 1893 Columbia Exposition in Chicago and at the 1900 Exposition Universelle.[165] While on tour in New York, she hosted a private viewing of her paintings and sculptures for 500 guests.[166] In 1880, she made an Art Nouveau decorative bronze inkwell, a self-portrait with bat wings and a fish tail,[167] possibly inspired by her 1874 performance in Le Sphinx.[168] She set up a studio at 11 boulevard de Clichy in Montmartre, where she frequently entertained her guests dressed in her sculptor's outfit, including white satin blouse and white silk trousers. Rodin dismissed her sculptures as "old-fashioned tripe", and she was attacked in the press for pursuing an activity inappropriate for an actress. She was defended by Émile Zola, who wrote "How droll! Not content with finding her thin, or declaring her mad, they want to regulate her daily activities...Let a law be passed immediately to prevent the accumulation of talent!"[169]

Memory and improvisation[edit]

Bernhardt had a remarkable ability to memorise a role quickly. She recounted in L'Art du Théâtre that "I only have to read a role two or three times and I know it completely; but the day that I stop playing the piece the role escapes me entirely...My memory can't contain several parts at the same time, and it's impossible for me to recite off-hand a tirade from Phèdre or Hamlet. And yet I can remember the smallest events from my childhood."[175] She also suffered, particularly early in her career, bouts of memory loss and stage fright. Once, she was seriously ill before a performance of L'Etrangère at the Gaiety Theatre in London, and the doctor gave her a dose of painkiller, either opium or morphine. During the performance, she went on stage, but could not remember what she was supposed to say. She turned to another actress, and announced, "If I made you come here, Madame, it is because I wanted to instruct you in what I want done...I have thought about it, and I do not want to tell you today", then walked offstage. The other actors, astonished, quickly improvised an ending to the scene. After a brief rest, her memory came back, and Bernhardt went back on stage, and completed the play.[175]

During another performance on her world tour, a backstage door was opened during a performance of Phèdre, and a cold wind blew across the stage as Bernhardt was reciting. Without interrupting her speech, she added "If someone doesn't close that door I will catch pneumonia." The door was closed, and no one in the audience seemed to notice the addition.[175]

Personal life[edit]

Paternity, date of birth, ancestry, name[edit]

The identity of Bernhardt's father is not known for certain. Her original birth certificate was destroyed when the Paris Commune burned the Hotel de Ville and city archives in May 1871. In her autobiography, Ma Double Vie,[186] she describes meeting her father several times, and writes that his family provided funding for her education, and left a sum of 100,000 francs for her when she came of age.[187] She said he frequently travelled overseas, and that when she was still a child, he died in Pisa "in unexplained circumstances which remain mysterious."[188] In February 1914, she presented a reconstituted birth certificate, which stated that her legitimate father was one Édouard Bernhardt.[189] On 21 May 1856, when she was baptised, she was registered as the daughter of "Edouard Bernhardt residing in Le Havre and Judith Van Hard, residing in Paris."[190]

A more recent biography by Hélène Tierchant (2009) suggests her father may have been a young man named De Morel, whose family members were notable shipowners and merchants in Le Havre. According to Bernhardt's autobiography, her grandmother and uncle in Le Havre provided financial support for her education when she was young, took part in family councils about her future, and later gave her money when her apartment in Paris was destroyed by fire.[187]

Her date of birth is also uncertain due to the destruction of her birth certificate. She usually gave her birthday as 23 October 1844, and celebrated it on that day. However, the reconstituted birth certificate she presented in 1914 gave the date as 25 October.[191][192] Other sources give the date 22 October,[193] or either 22 or 23 October.[2]

Bernhardt's mother Judith, or Julie, was born in the early 1820s. She was one of six children, five daughters and one son, of a Dutch-Jewish itinerant eyeglass merchant, Moritz Baruch Bernardt, and a German laundress,[194] Sara Hirsch (later known as Janetta Hartog or Jeanne Hard). Judith's mother died in 1829, and five weeks later, her father remarried.[195] His new wife did not get along with the children from his earlier marriage. Judith and two of her sisters, Henriette and Rosine, left home, moved to London briefly, and then settled in Le Havre, on the French coast.[194] Henriette married a local in Le Havre, but Julie and Rosine became courtesans, and Julie took the new, more French name of Youle and the more aristocratic-sounding last name of Van Hard. In April 1843, she gave birth to twin girls to a "father unknown." Both girls died in the hospice in Le Havre a month later. The following year, Youle was pregnant again, this time with Sarah. She moved to Paris, to 5 rue de l'École-de-Médecine, where in October 1844, Sarah was born.[196]

Lovers and friends[edit]

Early in Bernhardt's career, she had an affair with a Belgian nobleman, Charles-Joseph Eugène Henri Georges Lamoral de Ligne (1837–1914), son of Eugène, 8th Prince of Ligne, with whom she bore her only child, Maurice Bernhardt (1864–1928). Maurice did not become an actor, but worked for most of his life as a manager and agent for various theatres and performers, frequently managing his mother's career in her later years, but rarely with great success. Maurice and his family were usually financially dependent, in full or in part, on his mother until her death. Maurice married a Polish princess, Maria Jablonowska, of the House of Jablonowski, with whom he had two daughters: Simone, who married Edgar Gross, son of a wealthy Philadelphia soap manufacturer; and Lysiana, who married the playwright Louis Verneuil.

From 1864 to 1866, after Bernhardt left the Comédie-Française, and after Maurice was born, she frequently had trouble finding roles. She often worked as a courtesan, taking wealthy and influential lovers. The French police of the Second Empire kept files on high-level courtesans, including Bernhardt; her file recorded the wide variety of names and titles of her patrons; they included Alexandre Aguado, the son of Spanish banker and Marquis Alejandro María Aguado; the industrialist Robert de Brimont; the banker Jacques Stern; and the wealthy Louis-Roger de Cahuzac.[197] The list also included Khalil Bey, the Ambassador of the Ottoman Empire to the Second Empire, best known today as the man who commissioned Gustave Courbet to paint L'Origine du monde, a detailed painting of a woman's anatomy that was banned until 1995, but now on display at the Musée d'Orsay. Bernhardt received from him a diadem of pearls and diamonds. She also had affairs with many of her leading men, and with other men more directly useful to her career, including Arsène Houssaye, director of the Théâtre-Lyrique, and the editors of several major newspapers. Many of her early lovers continued to be her friends after the affairs ended.[198]

During her time at the Odéon, she continued to see her old lovers, as well as new ones including French marshals François-Certain Canrobert and Achille Bazaine, the latter a commander of the French army in the Crimean War and in Mexico; and Prince Napoleon, son of Joseph Bonaparte and cousin of French Emperor Louis-Napoleon. She also had a two-year-long affair with Charles Haas, son of a banker and one of the more celebrated Paris dandies in the Empire, the model for the character of Swann in the novels by Marcel Proust.[199] Indeed, Swann even references her by name in Remembrance of Things Past. Sarah Bernhardt is probably one of the actresses after whom Proust modelled Berma, a character present in several volumes of Remembrance of Things Past.

Bernhardt took as lovers many of the male leads of her plays, including Mounet-Sully and Lou Tellegen. She possibly had an affair with the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII, who frequently attended her London and Paris performances and once, as a prank, played the part of a cadaver in one of her plays.[200] When he was King, he travelled on the royal yacht to visit her at her summer home on Belle-Île.[201]

Her last serious love affair was with the Dutch-born actor Lou Tellegen, 37 years her junior, who became her co-star during her second American farewell tour (and eighth American tour) in 1910. He was a very handsome actor who had served as a model for sculpture Eternal Springtime by Auguste Rodin. He had little acting experience, but Bernhardt signed him as a leading man just before she departed on the tour, assigned him a compartment in her private railway car, and took him as her escort to all events, functions, and parties. He was not a particularly good actor, and had a strong Dutch accent, but he was successful in roles, such as Hippolyte in Phedre, where he could take off his shirt. At the end of the American tour, they had a dispute, he remained in the United States, and she returned to France. At first, he had a successful career in the United States and married operatic soprano and film actress Geraldine Farrar, but when they split up his career plummeted. He committed suicide in 1934.[202]

Bernhardt's broad circle of friends included the writers Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, his son Alexandre Dumas fils, Émile Zola, and the artist Gustave Doré. Her close friends included the painters Georges Clairin and Louise Abbéma, a French impressionist painter, some nine years her junior. This relationship was so close, the two women were rumoured to be lovers. In 1990, a painting by Abbéma, depicting the two on a boat ride on the lake in the bois de Boulogne, was donated to the Comédie-Française. The accompanying letter stated that the painting was "Peint par Louise Abbéma, le jour anniversaire de leur liaison amoureuse"[203] (loosely translated: "Painted by Louise Abbéma on the anniversary of their love affair") Clairin and Abbéma spent their holidays with Bernhardt and her family at her summer residence at Belle-Île, and remained close with Bernhardt until her death.[204]