Nanjing Massacre

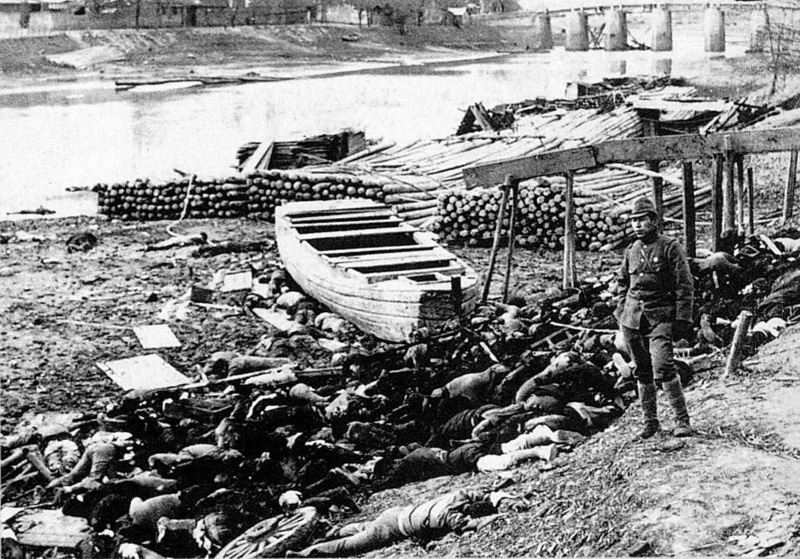

The Nanjing Massacre[2] or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as Nanking[note 2]) was the mass murder of Chinese civilians in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, immediately after the Battle of Nanking in the Second Sino-Japanese War, by the Imperial Japanese Army.[3][4][5][6] Beginning on December 13, 1937, the massacre lasted six weeks.[note 1] The perpetrators also committed other war crimes such as mass rape, looting, torture, and arson. The massacre is considered to be one of the worst wartime atrocities.[7][8][9]

For the book by Iris Chang, see The Rape of Nanking (book).Nanjing Massacre

From December 13, 1937, for six weeks[note 1]

200,000 (consensus), estimates range from 40,000 to over 300,000

20,000 to 80,000 women and children raped, 30,000 to 40,000 POWs executed

- Prince Yasuhiko Asaka (granted immunity)

- Gen. Iwane Matsui

- Lt. Col. Isamu Chō

The Japanese army had pushed quickly through China after capturing Shanghai in November 1937. As the Japanese approached Nanjing, they committed violent atrocities in a terror campaign, including killing contests and massacring entire villages.[10] By early December, their army had reached the outskirts of Nanjing.

The Chinese army withdrew the bulk of its forces since Nanjing was not a defensible position. The civilian government of Nanjing fled, leaving the city under the de facto control of German citizen John Rabe, who had founded the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone. On December 5, Prince Yasuhiko Asaka was installed as Japanese commander in the campaign. Whether Asaka ordered the Rape, or simply stood by as it happened, is disputed, but he took no action to stop the carnage.

The massacre officially began on December 13, the day Japanese troops entered the city after a ferocious battle. They rampaged through Nanjing almost unchecked. Captured Chinese soldiers were summarily executed in violation of the laws of war, as were numerous male civilians falsely accused of being soldiers. Rape and looting was widespread. Due to multiple factors, death toll estimates vary from 40,000 to over 300,000, with rape cases ranging from 20,000 to over 80,000 cases. However, most credible scholars in Japan, which include a large number of authoritative academics, support the validity of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East and its findings, which estimate at least 200,000 murders and at least 20,000 cases of rape. The massacre finally wound down in early 1938. John Rabe's Safety Zone was mostly a success, and is credited with saving at least 200,000 lives. After the war, multiple Japanese military officers and Kōki Hirota, former Prime Minister of Japan and foreign minister during the atrocities, were found guilty of war crimes and executed. Some other Japanese military leaders in charge at the time of the Nanjing Massacre were not tried only because by the time of the tribunals they had either already been killed or committed seppuku (ritual suicide). Prince Asaka, as part of the Imperial Family, was granted immunity and never tried.

The massacre has remained a wedge issue between modern China and Japan. Historical revisionists and nationalists in Japan have been accused of minimizing or denying the massacre.

Military situation

In August 1937, the Japanese army invaded Shanghai, where they met strong resistance and suffered heavy casualties. The battle was bloody as both sides faced attrition in urban hand-to-hand combat.[11] By mid-November, the Japanese had captured Shanghai with the help of naval and aerial bombardment. The General Staff Headquarters in Tokyo initially decided not to expand the war due to the high casualties incurred and the low morale of the troops.[12] Nevertheless, on December 1, headquarters ordered the Central China Area Army and the 10th Army to capture Nanjing, then-capital of the Republic of China.

Civilian evacuation

With the relocation of the capital of China and the reports of Japanese brutality, most of the civilian population fled Nanjing out of fear. Wealthy families were the first to flee, leaving Nanjing in automobiles, followed by the evacuation of the middle class and then the poor, while only the destitute lowest class such as the ethnic Tanka boat people remained behind.[8] Half of the population had fled Nanjing before the Japanese arrived.[43]

Nanjing Massacre

南京大屠殺

南京大屠杀

Nánjīng Dàtúshā

Nánjīng Dàtúshā

Nan2-ching1 Ta4-t'u2-sha1

1. 南京大虐殺

2. 南京事件

1. Nankin Daigyakusatsu (Nanjing Massacre)

2. Nankin Jiken (Nanjing Incident, name used in Japanese media)[44]

1. Nankin Daigyakusatsu (Nanjing Massacre)

2. Nankin Jiken (Nanjing Incident, name used in Japanese media)[44]

End of the massacre

In late January 1938, the Japanese army forced all refugees in the Safety Zone to return home, immediately claiming to have "restored order". After the establishment of the weixin zhengfu (the collaborating government) in 1938, order was gradually restored in Nanjing and atrocities by Japanese troops lessened considerably.

On 18 February 1938, the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone was forcibly renamed the Nanjing International Rescue Committee, and the Safety Zone effectively ceased to function. The last refugee camps were closed in May 1938.

Recall of Matsui and Asaka

In February 1938, both Prince Asaka and General Matsui were recalled to Japan. Matsui returned to retirement, but Prince Asaka remained on the Supreme War Council until the end of the war in August 1945. He was promoted to the rank of general in August 1939, though he held no further military commands.[37]

Evidence collection

The Japanese either destroyed or concealed important documents, severely reducing the amount of evidence available for confiscation. Between the declaration of a ceasefire on August 15, 1945, and the arrival of American troops in Japan on August 28, "the Japanese military and civil authorities systematically destroyed military, naval, and

government archives, much of which was from the period 1942–1945."[106] Overseas troops in the Pacific and East Asia were ordered to destroy incriminating evidence of war crimes.[106] Approximately 70 percent of the Japanese army's wartime records were destroyed.[106]

In regards to the Nanjing Massacre, Japanese authorities deliberately concealed wartime records, eluding confiscation from American authorities.[107] Some of the concealed information was made public a few decades later. For example, a two-volume collection of military documents related to the Nanjing operations was published in 1989; and disturbing excerpts from Kesago Nakajima's diary, a commander at Nanjing, was published in the early 1980s.[107]

Ono Kenji, a chemical worker in Japan, curated a collection of wartime diaries from Japanese veterans who fought in the Battle of Nanking in 1937.[108] In 1994, nearly 20 diaries in his collection were published, which became an important source of evidence for the massacre. Official war journals and diaries were also published by Kaikosha, an organization of retired Japanese military veterans.[108]

In early 1980s, after interviewing Chinese survivors and reviewing Japanese records, Japanese journalist Honda Katsuichi concluded that the Nanjing Massacre was not an isolated case, and that Japanese atrocities against the Chinese were common throughout the Lower Yangtze River since the battle of Shanghai.[109] The diaries of other Japanese combatants and medics who fought in China have corroborated his conclusions.[110]

On October 9, 2015, Documents of the Nanjing Massacre have been listed on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register.[130]

Legacy

Effect on international relations

The memory of the Nanjing Massacre has been a point of contention in Sino-Japanese relations since the early 1970s.[183] Trade between the two nations is worth over $200 billion annually. Despite this, many Chinese people still have a strong sense of mistrust due to the memory of the atrocity and failure of reconciliation measures. This sense of mistrust is strengthened by Japan's unwillingness to admit to and apologize for the atrocities.[184]

Takashi Yoshida described how changing political concerns and perceptions of the "national interest" in Japan, China, and the U.S. have shaped the collective memory of the Nanjing massacre. Yoshida contended that over time the event has acquired different meanings to different people. People from mainland China saw themselves as the victims. For Japan, it was a question they needed to answer but were reluctant to do so because they too identified themselves as victims after the A-bombs. The U.S., which served as the melting pot of cultures and is home to descendants of members of both Chinese and Japanese cultures, took up the mantle of investigator for the victimized Chinese. Yoshida has argued that the Nanjing Massacre has figured in the attempts of all three nations as they work to preserve and redefine national and ethnic pride and identity, assuming different kinds of significance based on each country's changing internal and external enemies.[185]

Many Japanese prime ministers have visited the Yasukuni Shrine, a shrine for Japanese war deaths up until the end of the Second World War, which includes war criminals that were involved in the Nanjing Massacre. In the museum adjacent to the shrine, a panel informs visitors that there was no massacre in Nanjing, but that Chinese soldiers in plain clothes were "dealt with severely". In 2006 former Japanese prime minister Junichiro Koizumi made a pilgrimage to the shrine despite warnings from China and South Korea. His decision to visit the shrine regardless sparked international outrage. Although Koizumi denied that he was trying to glorify war or historical Japanese militarism, the Chinese Foreign Ministry accused Koizumi of "wrecking the political foundations of China-Japan relations". An official from South Korea said they would summon the Tokyo ambassador to protest.[186][187]

The Massacre is sometimes compared to other disasters in China, which include the Great Chinese famine (1959–1961)[188][189][190] and the Cultural Revolution.[191][192][193]

As a component of national identity

Yoshida asserts that "Nanjing has figured in the attempts of all three nations [China, Japan and the United States] to preserve and redefine national and ethnic pride and identity, assuming different kinds of significance based on each country's changing internal and external enemies."[194]

Records

In December 2007, the PRC government published the names of 13,000 people who were killed by Japanese troops in the Nanjing Massacre. According to Xinhua News Agency, it is the most complete record to date. The report consists of eight volumes and was released to mark the 70th anniversary of the start of the massacre. It also lists the Japanese army units that were responsible for each of the deaths and states the way in which the victims were killed. Zhang Xianwen, editor-in-chief of the report, states that the information collected was based on "a combination of Chinese, Japanese and Western raw materials, which is objective and just and is able to stand the trial of history".[211] This report formed part of a 55-volume series about the massacre, the Collection of Historical Materials of Nanjing Massacre (南京大屠杀史料集).

![General Iwane Matsui[136]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c1/Iwane_Matsui.jpg/110px-Iwane_Matsui.jpg)

![General Hisao Tani[137]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c0/Tani_Hisao.jpg/139px-Tani_Hisao.jpg)