Naram-Sin of Akkad

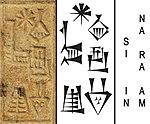

Naram-Sin, also transcribed Narām-Sîn or Naram-Suen (Akkadian: 𒀭𒈾𒊏𒄠𒀭𒂗𒍪: DNa-ra-am DSîn, meaning "Beloved of the Moon God Sîn", the "𒀭" a determinative marking the name of a god), was a ruler of the Akkadian Empire, who reigned c. 2254–2218 BC (middle chronology), and was the third successor and grandson of King Sargon of Akkad. Under Naram-Sin the empire reached its maximum extent. He was the first Mesopotamian king known to have claimed divinity for himself, taking the title "God of Akkad", and the first to claim the title "King of the Four Quarters". He became the patron city god of Akkade as Enlil was in Nippur.[1] His enduring fame resulted in later rulers, Naram-Sin of Eshnunna and Naram-Sin of Assyria as well as Naram-Sin of Uruk, assuming the name.[2][3]

For other people named Naram-Sin, see Naram-Sin (disambiguation).

Naram-Sin

𒀭𒈾𒊏𒄠𒀭𒂗𒍪

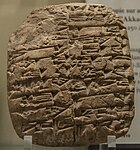

Naram-Sin's Victory Stele depicts him as a god-king (symbolized by his horned helmet) climbing a mountain above his soldiers, and his enemies, the defeated Lullubi led by their king Satuni. The stele was broken off at the top apparently when it was carried away from Sippar and carried off by the Elamite forces of Shutruk-Nakhunte in the 12th century BC along with a number of other monuments.[40] The stele seems to break from tradition by using successive diagonal tiers to communicate the story to viewers, however the more traditional horizontal frames are visible on smaller broken pieces.[41] It has been suggested that it contains the first depictions of battle standards and plate armor.[42] The stele is 200 centimeters tall and 105 centimeters wide and is made from pinkish limestone. For contrast see the Victory Stele of Rimush over Lagash or the Victory stele of Sargon.[43][44] The stele was found by Jacques de Morgan at Susa, and is now in the Louvre Museum (Sb 4).[45]

The inscription over the head of the king is in the Akkadian language and very fragmentary, but reads:

Shutruk-Nahhunte added his own inscription to the stele, in Middle Elamite:

A similar stele fragment (ES 1027), 57 centimeters high by 42 centimeters wide by 20 deep, depicting Naram-Sin was found a few miles north-east of Diarbekr, at Pir Hüseyin in a well, though this was not its original context. It is said to have been first found Miyafarkin, a village about 75 kilometers northeast of Diarbekr.[47]

Fragments of an alabaster stele representing captives being led by Akkadian soldiers is sometimes attributed to Narim-Sin (or Rimush or Manishtushu) on stylistic grounds.[48] In particular, it is considered as more sophisticated graphically than the steles of Sargon of Akkad or those of Rimush or Manishitshu.[48] Two fragments (IM 55639 and IM 59205) are in the National Museum of Iraq, and one (MFA 66.89) is the Boston Museum.[48] The stele is quite fragmentary, but attempts at reconstitution have been made.[49][48] Depending on sources, the fragments were excavated in Wasit, al-Hay district, Wasit Governorate, or in Nasiriyah, both locations in Iraq.[50]

It is thought that the stele represents the result of the campaigns of Naram-Sin to Cilicia or Anatolia. This is suggested by the characteristics of the booty carried by the soldiers in the stele, especially the metal vessel carried by the main soldier, the design of which is unknown in Mesopotamia, but on the contrary well known in contemporary Anatolia.[48]

![Alabaster vase in the name of "Naran-Sin, King of the four regions" '(𒀭𒈾𒊏𒄠𒀭𒂗𒍪 𒈗 𒆠𒅁𒊏𒁴 𒅈𒁀𒅎 DNa-ra-am DSîn lugal ki-ibratim arbaim), limestone, c. 2250 BC. Louvre Museum AO 74.[56]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9e/Vase_in_the_name_of_Naran-Sin_King_of_the_four_region%2C_limestone%2C_circa_2250_BCE.jpg/96px-Vase_in_the_name_of_Naran-Sin_King_of_the_four_region%2C_limestone%2C_circa_2250_BCE.jpg)

!["Naran-Sin, King of the four regions" '(𒀭𒈾𒊏𒄠𒀭𒂗𒍪 𒈗 𒆠𒅁𒊏𒁴 𒅈𒁀𒅎 DNa-ra-am DSîn lugal ki-ibratim arbaim), limestone, c. 2250 BC. Louvre Museum AO 74.[56]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b1/Naram-Sin%2C_King_of_the_Four_quarters_of_the_World.jpg/150px-Naram-Sin%2C_King_of_the_Four_quarters_of_the_World.jpg)

![This bronze head traditionally attributed to Sargon is now thought to actually belong to his grandson Naram-Sin.[48]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/df/Bronze_head_of_an_Akkadian_ruler%2C_discovered_in_Nineveh_in_1931%2C_presumably_depicting_either_Sargon_or_Sargon%27s_grandson_Naram-Sin_%28Rijksmuseum_van_Oudheden%29.jpg/104px-thumbnail.jpg)

![Fragment of a stone bowl with an inscription of Naram-Sin, and a second inscription by Shulgi (upside down). Ur, Iraq. British Museum.[57][58]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1e/Fragment_of_a_stone_bowl_with_2_inscriptions%2C_from_Ur%2C_Iraq._British_Museum.jpg/150px-Fragment_of_a_stone_bowl_with_2_inscriptions%2C_from_Ur%2C_Iraq._British_Museum.jpg)

![Rock relief image at Darband-i-Gawr originally thought to be of Naram-Sin but since in dispute.[59][60]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b1/Naram-Sin_Rock_Relief_at_Darband-iGawr_%28extracted%29.jpg/92px-Naram-Sin_Rock_Relief_at_Darband-iGawr_%28extracted%29.jpg)

![Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, c. 2230 BC. It shows him defeating the Lullibi, a tribe in the Zagros Mountains, and their king Satuni, trampling them and spearing them. Satuni, standing right, is imploring Naram-Sin to save him.[61] Naram-Sin is also twice the size of his soldiers.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/67/Stele_Naram_Sim_Louvre_Sb4.jpg/150px-Stele_Naram_Sim_Louvre_Sb4.jpg)