No Fly List

The No Fly List, maintained by the United States federal government's Terrorist Screening Center (TSC), is one of several lists included in algorithmic rulesets used by government agencies and airlines to decide who to allow to board airline flights.[1] The TSC's No Fly List is a list of people who are prohibited from boarding commercial aircraft for travel within, into, or out of the United States. This list has also been used to divert aircraft away from U.S. airspace that do not have start- or end-point destinations within the United States. The number of people on the list rises and falls according to threat and intelligence reporting. There were reportedly 16,000[2] names on the list in 2011, 21,000 in 2012, and 47,000 in 2013.

This article is about the American list. For the Indian list, see No Fly List (India). For the Canadian list, see Passenger Protect. For other uses, see No Fly List (disambiguation).

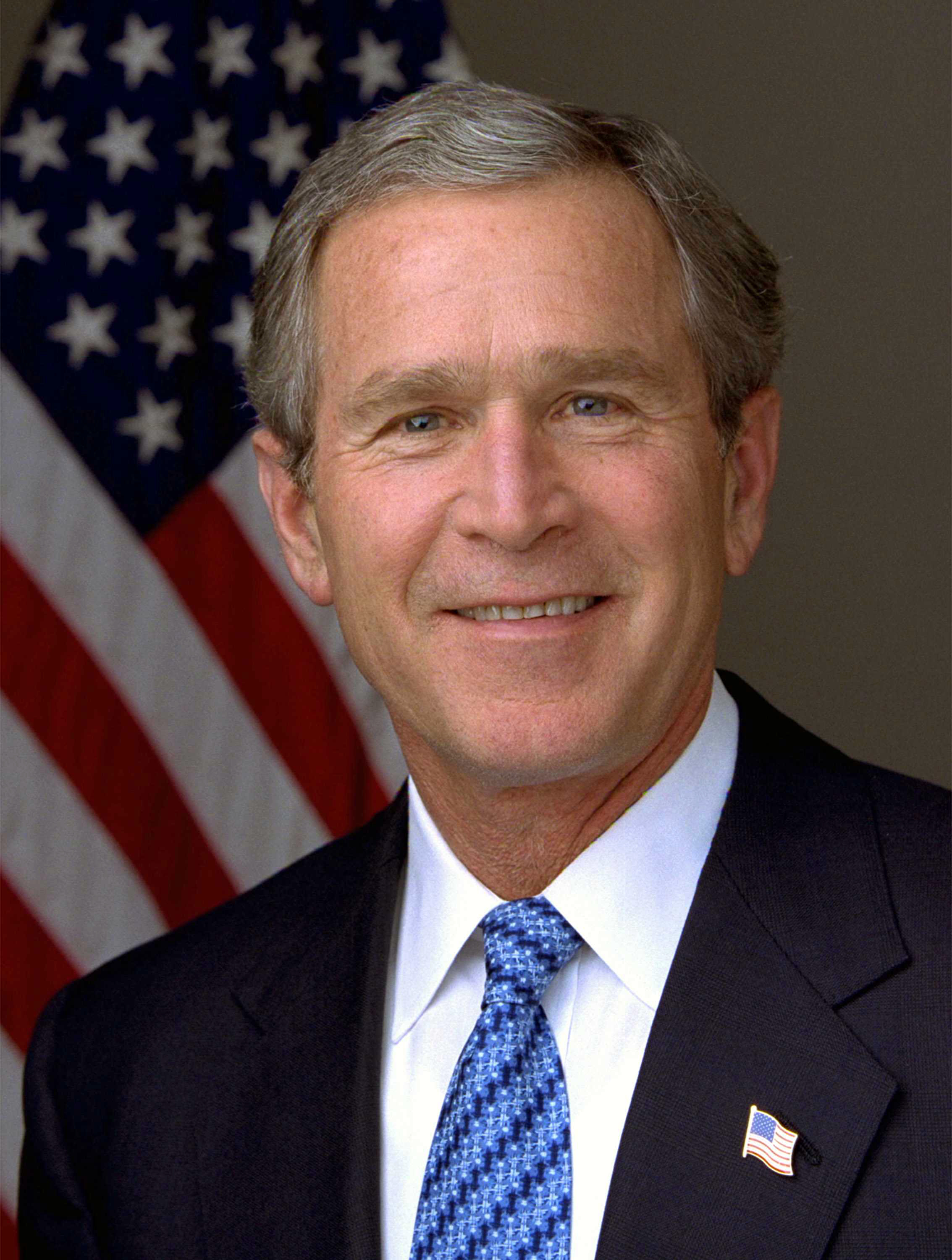

The list—along with the Secondary Security Screening Selection, which tags would-be passengers for extra inspection—was created after the September 11 attacks of 2001. The No Fly List, the Selectee List, and the Terrorist Watch List were created by George W. Bush's administration and have continued through the administrations of Barack Obama, Donald Trump and Joe Biden. Former U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee chair Dianne Feinstein said in May 2010: "The no-fly list itself is one of our best lines of defense."[3] However, the list has been criticized on civil liberties and due process grounds, due in part to its potential for ethnic, religious, economic, political, or racial profiling and discrimination. It has raised concerns about privacy and government secrecy and has been criticized as prone to false positives.

The No Fly List is different from the Terrorist Watch List, a much longer list of people said to be suspected of some involvement with terrorism. As of June 2016, the Terrorist Watch List is estimated to contain over 2,484,442 records, consisting of 1,877,133 individual identities.[4][5]

History[edit]

Before the attacks of September 11, 2001, the U.S. federal government had a list of 16 people deemed "no transport" because they "presented a specific known or suspected threat to aviation."[6][7] The list grew in the immediate aftermath of the September 11 attacks, reaching more than 400 names by November 2001, when responsibility for keeping it was transferred to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).[7] In mid-December 2001, two lists were created: the "No Fly List" of 594 people to be denied air transport, and the "Selectee" list of 365 people who were to be more carefully searched at airports.[6][7] By 2002, the two lists combined contained over a thousand names, and by April 2005 contained about 70,000 names.[6] For the first two and a half years of the program, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and Transportation Security Administration (TSA) denied that the program existed.[6]

In 2004, then-U.S. Senator Edward Kennedy was denied boarding a flight because his name was similar to an alias found on the No Fly List.[8] Laura K. Donohue would later write in The Cost of Counterterrorism: Power, Politics, and Liberty that "antiwar activists, such as Jan Adams and Rebecca Gordan, and political opponents of the Bush administration, such as Senator Edward Kennedy and civil rights attorney David Cole, found themselves included."[6] In June 2016, Timothy Healy, the former director of the FBI Terrorist Screening Center, disputed the claim that Kennedy had ever appeared on the list, saying that another person with a similar name—who had accidentally tried to bring ammunition on to a plane—was placed on an airline's watch list and Kennedy was mistakenly detained by the airline, not based on the No Fly List.[9] In October 2006, CBS News' 60 Minutes reported on the program after it obtained a March 2006 copy of the list containing 44,000 names.[10]

Many individuals were "caught in the system" as a result of sharing the exact or similar name of another person on the list;[6] TSA officials said that, as of November 2005, 30,000 people in 2005 had complained that their names were matched to a name on the list via the name matching software used by airlines.[11] In January 2006, the FBI and ACLU settled a federal lawsuit, Gordon v. FBI, brought by Gordon and Adams under the Freedom of Information Act in order to obtain information about how names were added to the list.[11] Under the settlement, the government paid $200,000 in the plaintiffs' attorneys' fees.[12] A separate suit was brought as a class action "filed by people caught in the name game."[6] In response, "TSA created an ombudsman process, whereby individuals now can download and print out a Passenger Identity Verification Form and mail it, along with certain notarized documents, to the TSA 'so the agency can differentiate the individual from others who may be on the list.'"[6]

In April 2007, the U.S. federal government's "terrorist watch list" administered by the Terrorist Screening Center (which is managed principally by the FBI)[13] contained 700,000 records.[14] A year later, the ACLU estimated the list to have grown to over 1,000,000 names and to be continually expanding.[15][16][17] However, according to Homeland Security secretary Michael Chertoff, in October 2008 the No Fly List contained only 2,500 names, with an additional 16,000 "selectees" who "represent a less specific security threat and receive extra scrutiny, but are allowed to fly."[18]

As of 2011, the list contained about 10,000 names.[19][20] In 2012, the list more than doubled in size, to about 21,000 names.[21] In August 2013, a leak revealed that more than 47,000 people were on the list.[22][13] In 2016, California Senator Dianne Feinstein disclosed that 81,000 people were on the No Fly List.[23]

There is a huge, secretive US anti-terrorism database for Canada specifically, "Tuscan" (Tipoff US/Canada), revealed by Canada's access to information system. The database is used by both the US and Canada, and applies to all borders, not just airports. It is believed to contain information on about 680,000 people thought to be linked with terrorism. The list was created in 1997 as a consular aid. It was repurposed and expanded after 9/11, and again in 2016. The names in Tuscan come from the US Terrorist Identities Datamart Environment (Tide), which is vetted by the FBI's Terrorist Screening Center and populates various US traveller databases, Canada's Tuscan and the Australian equivalent, "Tactics".[24]

Weapons purchases by listed persons (No Fly No Buy)[edit]

In a 2010 report, the Government Accountability Office noted that "Membership in a terrorist organization does not prohibit a person from possessing firearms or explosives under current federal law," and individuals on the No Fly List are not barred from purchasing guns.[25] According to GAO data, between 2004 and 2010, people on terrorism watch lists—including the No Fly List as well as other separate lists—attempted to buy guns and explosives more than 1,400 times, and succeeded 1,321 times (more than 90% of cases).[26]

Senator Frank Lautenberg of New Jersey repeatedly introduced legislation to bar individuals on the terror watch lists (such as the No Fly List) from buying firearms or explosives, but these efforts have not succeeded.[25][26][27] Senator Dianne Feinstein of California revived the legislation after the November 2015 Paris attacks and President Barack Obama has called for such legislation to be approved.[25]

Republicans in Congress such as Senate Homeland Security Committee chair Ron Johnson and former Speaker of the House Paul Ryan oppose this measure, citing due process concerns and efficacy, respectively.[25] Republicans have blocked attempts by Democrats to attach these provisions to Republican-backed measures.[28]

The American Civil Liberties Union has voiced opposition to barring weapons sales to individuals listed on the current form of the No Fly List, stating that: "There is no constitutional bar to reasonable regulation of guns, and the No Fly List could serve as one tool for it, but only with major reform."[29] Specifically, the ACLU's position is that the government's current redress process—the procedure by which listed individuals can petition for removal from the list—does not meet the requirements of the Constitution's Due Process Clause because the process does not "provide meaningful notice of the reasons our clients are blacklisted, the basis for those reasons, and a hearing before a neutral decision-maker."[29]

In December 2015, Feinstein's amendment to bar individuals on the terror watch list from purchasing firearms failed in the Senate on a 45-54 vote.[30] Senate Majority Whip John Cornyn of Texas put forth a competing proposal to "give the attorney general the power to impose a 72-hour delay for individuals on the terror watch list seeking to purchase a gun and it could become a permanent ban if a judge determines there is probable cause during that time window."[30] The measure, too, failed, on a 55-45 vote (60 votes were required to proceed).[30] The votes on both the Feinstein measure and the Cornyn measure were largely along party lines.[30]

No fly lists in other countries[edit]

Canada's federal government has created its own no fly list as part of a program called Passenger Protect.[100] The Canadian list incorporates data from domestic and foreign intelligence sources, including the U.S. No Fly List.[101] It contains between 500 and 2,000 names.[102]

In addition, Canada's access to information system revealed that the US "Tuscan" (Tipoff US/Canada) database is provided to every Canadian border guard and immigration officer; they have the power to detain, interrogate, arrest and deny entry to anyone listed on it. Unlike the no-fly list, which only applies to airports, Tuscan is used for every Canadian land and sea border, and visa and immigration application.[24]

In Pakistan, the no fly list is known as the Exit Control List.[103]