On Vision and Colours

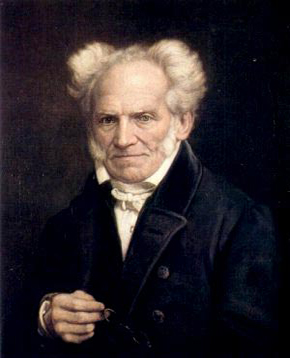

On Vision and Colors (originally translated as On Vision and Colours; German: Ueber das Sehn und die Farben) is a treatise[1] by Arthur Schopenhauer that was published in May 1816 when the author was 28 years old. Schopenhauer had extensive discussions with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe about the poet's Theory of Colours of 1810, in the months around the turn of the years 1813 and 1814, and initially shared Goethe's views.[2] Their growing theoretical disagreements and Schopenhauer's criticisms made Goethe distance himself from his young collaborator.[3] Although Schopenhauer considered his own theory superior, he would still continue to praise Goethe's work as an important introduction to his own.[4]

Schopenhauer tried to demonstrate physiologically that color is "specially modified activity of the retina."[5] The initial basis for Schopenhauer's color theory comes from Goethe's chapter on physiological colors, which discusses three principal pairs of contrasting colors: red/green, orange/blue, and yellow/violet. This is in contrast to the customary emphasis on Newton's seven colors of the Newtonian spectrum. In accordance with Aristotle, Schopenhauer considered that colors arise by the mixture of shadowy, cloudy darkness with light. With white and black at each extreme of the scale, colors are arranged in a series according to the mathematical ratio between the proportions of light and darkness. Schopenhauer agreed with Goethe's claim that the eye tends toward a sum total that consists of a color plus its spectrum or afterimage. Schopenhauer arranged the colors so that the sum of any color and its complementary afterimage always equals unity. The complete activity of the retina produces white. When the activity of the retina is divided, the part of the retinal activity that is inactive and not stimulated into color can be seen as the ghostly complementary afterimage, which he and Goethe call a (physiological) spectrum.

History[edit]

Schopenhauer met Goethe in 1808 at his mother's parties in Weimar but Goethe then mostly ignored the young and unknown student. In November 1813, Goethe congratulated Schopenhauer on his doctoral dissertation On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason which he received as a gift. Both men shared the opinion that visual representations yielded more knowledge than did concepts. In the winter of 1813/1814, Goethe personally demonstrated his color experiments to Schopenhauer and they discussed color theory. Goethe encouraged Schopenhauer to write On Vision and Colors. Schopenhauer wrote it in a few weeks while living in Dresden in 1815. After it was published, in July 1815, Goethe rejected several of Schopenhauer's conclusions, especially as to whether white is a mixture of colors. He was also disappointed that Schopenhauer considered the whole topic of color to be a minor issue. Schopenhauer wrote as though Goethe had merely gathered data while Schopenhauer provided the actual theory. A major difference between the two men was that Goethe considered color to be an objective property of light and darkness.[6] Schopenhauer's Kantian transcendental idealism was opposed to Goethe's realism.[7] For Schopenhauer, color was subjective in that it exists totally in the spectator's retina. As such, it can be excited in various ways by external stimuli or internal bodily conditions. Light is only one kind of color stimulus.

In 1830, Schopenhauer published a revision of his color theory. The title was Theoria colorum Physiologica, eademque primaria (Fundamental physiological theory of color). It appeared in Justus Radius's Scriptores ophthalmologici minores (Minor ophthalmological writings). "This is no mere translation of the first edition," he wrote, "but differs noticeably from it in form and presentation and is also amply enriched in subject matter."[8] Because it was written in Latin, he believed that foreign readers would be able to appreciate its value.

An improved second edition of On Vision and Colors was published in 1854. In 1870, a third edition was published, edited by Julius Frauenstädt. In 1942, an English translation by Lt. Col. E. F. J. Payne was published in Karachi, India. This translation was republished in 1994 by Berg Publishers, Inc., edited by Professor David E. Cartwright.

Content[edit]

Preface to the second edition (the first edition had no Preface)[edit]

Although this work is mainly concerned with physiology,[9] it is of philosophical value. In gaining knowledge of the subjective nature of color, the reader will have a more profound understanding of Kant's doctrine of the a priori, subjective, intellectual forms of all knowledge. This is in opposition to contemporary realism which simply takes objective experience as positively given. Realism doesn't consider that it is through the subjective that the objective exists. The observer's brain stands like a wall between the observing subject and the real nature of things.

Introduction[edit]

Goethe performed two services: (1) he freed color theory from its reliance on Newton, and (2) he provided a systematic presentation of data for a theory of color.

Before discussing color, there are some preliminary remarks to be made regarding vision. In § 1, it is shown that the perception of externally perceived objects in space is a product of the intellect's understanding after it has been stimulated by sensation from the sense organs. These remarks are necessary in order for the reader to be convinced that colors are entirely in the eye alone and are thoroughly subjective[10]

Reception[edit]

Ludwig Wittgenstein and Erwin Schrödinger were strongly influenced by Schopenhauer's works and both seriously investigated color theory. Philipp Mainländer considered the work to be among the most important things ever written.[21] Johannes Itten based his work on Schopenhauer's theory of color.

The mathematician Brouwer wrote: "Newton's theory of color analyzed light rays in their medium, but Goethe and Schopenhauer, more sensitive to the truth, considered color to be the polar splitting by the human eye."[22]

The physicist Ernst Mach praised that "men such as Goethe, Schopenhauer" had started to "investigate the sensations themselves" on the first page of his work Die Analyse der Empfindungen und das Verhältnis des Physischen zum Psychischen.[23]

According to Rudolf Arnheim, Schopenhauer's "...basic conception of complementary pairs in retinal functioning strikingly anticipates the color theory of Ewald Hering."[24] Nietzsche noted that the Bohemian physiologist, Professor Czermak, acknowledged Schopenhauer's relation to the Young-Helmholtz theory of color.[25] Bosanquet claimed that Schopenhauer's color theory was in accord with scientific research.[26]