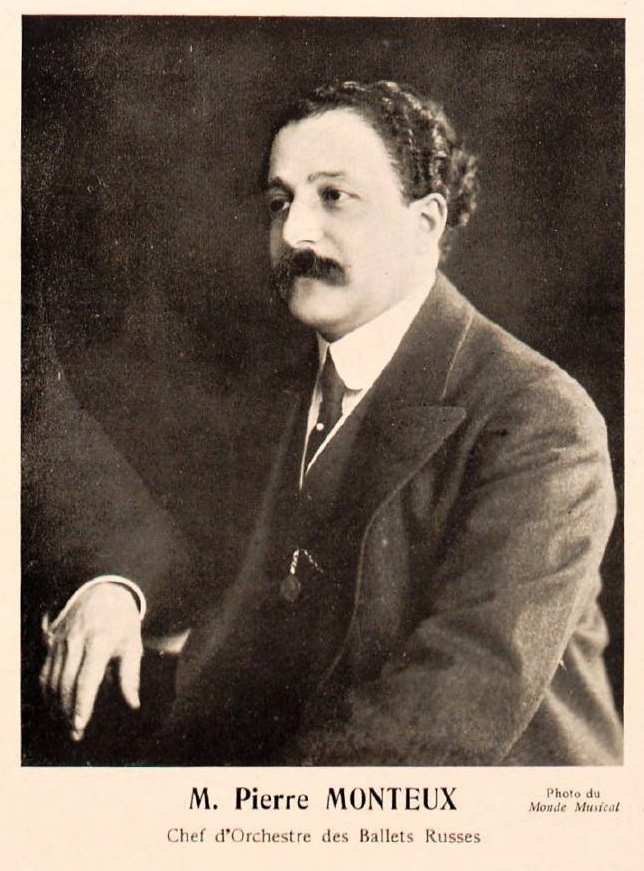

Pierre Monteux

Pierre Benjamin Monteux (pronounced [pjɛʁ mɔ̃.tø]; 4 April 1875 – 1 July 1964)[n 1] was a French (later American) conductor. After violin and viola studies, and a decade as an orchestral player and occasional conductor, he began to receive regular conducting engagements in 1907. He came to prominence when, for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes company between 1911 and 1914, he conducted the world premieres of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring and other prominent works including Petrushka, The Nightingale, Ravel's Daphnis et Chloé, and Debussy's Jeux. Thereafter he directed orchestras around the world for more than half a century.

From 1917 to 1919 Monteux was the principal conductor of the French repertoire at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. He conducted the Boston Symphony Orchestra (1919–24), Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra (1924–34), Orchestre Symphonique de Paris (1929–38) and San Francisco Symphony (1936–52). In 1961, aged eighty-six, he accepted the chief conductorship of the London Symphony Orchestra, a post which he held until his death three years later. Although he was known for his performances of the French repertoire, his chief love was the music of German composers, above all Brahms. He disliked recording, finding it incompatible with spontaneity, but he nevertheless made a substantial number of records.

Monteux was well known as a teacher. In 1932 he began a conducting class in Paris, which he developed into a summer school that was later moved to his summer home in Les Baux in the south of France. After moving permanently to the US in 1942 and taking American citizenship, he founded a school for conductors and orchestral musicians in Hancock, Maine. Among his students in France and America who went on to international fame were Lorin Maazel, Igor Markevitch, Neville Marriner, Seiji Ozawa, André Previn and David Zinman. The school in Hancock has continued since Monteux's death.

Life and career[edit]

Early years[edit]

Pierre Monteux was born in Paris, the third son and the fifth of six children of Gustave Élie Monteux, a shoe salesman, and his wife, Clémence Rebecca née Brisac.[2] The Monteux family was descended from Sephardic Jews who settled in the south of France.[3] The Monteux ancestors included at least one rabbi, but Gustave Monteux and his family were not religious.[4] Among Monteux's brothers were Henri, who became an actor, and Paul (1862-1928), who became a conductor of light music under the name Paul Monteux-Brisac.[5] Gustave Monteux was not musical, but his wife was a graduate of the Conservatoire de Musique de Marseille and gave piano lessons.[2] Pierre took violin lessons from the age of six.[2]

Personal life[edit]

Monteux had six children, two of them adopted. From his first marriage there were a son, Jean-Paul, and a daughter, Suzanne. Jean-Paul became a jazz musician, performing with artists such as Josephine Baker and Mistinguett.[10] His second marriage produced a daughter, Denise, later known as a sculptress, and a son, Claude, a flautist.[146] After Monteux married Doris Hodgkins he legally adopted her two children, Donald, later a restaurateur, and Nancie, who after a career as a dancer became administrator of the Pierre Monteux School in Hancock.[108]

Among Monteux's numerous honours, he was a Commandeur of the Légion d'honneur and a Knight of the Order of Oranje-Nassau.[7] A political and social moderate, in the politics of his adopted homeland he supported the Democratic Party[132] and was a strong opponent of racial discrimination. He ignored taboos on employing black artists;[147] reportedly, during the days of segregation in the US, when told he could not be served in a restaurant "for colored folk" he insisted that he was coloured – pink.[148]

Music making[edit]

Reputation and repertoire[edit]

The record producer John Culshaw described Monteux as "that rarest of beings – a conductor who was loved by his orchestras ... to call him a legend would be to understate the case."[149] Toscanini observed that Monteux had the best baton technique he had ever seen.[130] Like Toscanini, Monteux insisted on the traditional orchestral layout with first and second violins to the conductor's left and right, believing that this gave a better representation of string detail than grouping all the violins together on the left.[n 15] On fidelity to composers' scores, Monteux's biographer John Canarina ranks him with Klemperer and above even Toscanini, whose reputation for strict adherence to the score was, in Canarina's view, less justified than Monteux's.[151]