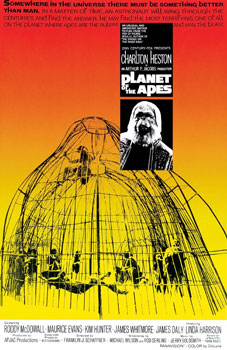

Planet of the Apes (1968 film)

Planet of the Apes is a 1968 American science fiction film directed by Franklin J. Schaffner from a screenplay by Michael Wilson and Rod Serling, loosely based on the 1963 novel by Pierre Boulle. The film stars Charlton Heston, Roddy McDowall, Kim Hunter, Maurice Evans, James Whitmore, James Daly, and Linda Harrison. In the film, an astronaut crew crash-lands on a strange planet in the distant future. Although the planet appears desolate at first, the surviving crew members stumble upon a society in which apes have evolved into creatures with human-like intelligence and speech. The apes have assumed the role of the dominant species and humans are mute creatures wearing animal skins.

Planet of the Apes

- February 8, 1968 (Capitol Theatre)

- April 3, 1968 (United States)

112 minutes[1]

United States

English

$5.8 million[2]

$33.3 million[2]

The outline Planet of the Apes script, originally written by Serling, underwent many rewrites before filming eventually began.[3] Directors J. Lee Thompson and Blake Edwards were approached, but the film's producer Arthur P. Jacobs, upon the recommendation of Heston, chose Franklin J. Schaffner to direct the film. Schaffner's changes included an ape society less advanced—and therefore less expensive to depict—than that of the original novel.[4] Filming took place between May 21 and August 10, 1967, in California, Utah, and Arizona, with desert sequences shot in and around Lake Powell, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. The film's final "closed" cost was $5.8 million.

Planet of the Apes premiered on February 8, 1968, at the Capitol Theatre in New York City, and was released in the United States on April 3, by 20th Century-Fox. The film was a box-office hit, earning a lifetime domestic gross of $33.3 million.[2] It was groundbreaking for its prosthetic makeup techniques by artist John Chambers[5] and was well received by audiences and critics, being nominated for Best Costume Design and Best Original Score at the 41st Academy Awards, and winning an honorary Academy Award for Chambers. In 2001, Planet of the Apes was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[6][7]

Planet of the Apes' success launched a franchise,[8] including four sequels, as well as a television series, animated series, comic books, and various merchandising. In particular, Roddy McDowall had a long-running relationship with the franchise, appearing in four of the original five films (he was absent from the second film, Beneath the Planet of the Apes, in which he was replaced by David Watson in the role of Cornelius) and also in the television series. The original film series was followed by Tim Burton's remake of the same name in 2001 and a reboot series, which began with Rise of the Planet of the Apes in 2011.[9]

Production[edit]

Origins[edit]

Producer Arthur P. Jacobs bought the rights for the Pierre Boulle novel before its publication in 1963. Jacobs pitched the production to many studios, and in late 1964, the project was announced as a Warner Bros. production, with Blake Edwards attached to direct.[10] After Jacobs made a successful debut as a producer doing What a Way to Go! (1964) for 20th Century-Fox and begun pre-production of another film for the studio, Doctor Dolittle, he managed to convince Fox vice-president Richard D. Zanuck to greenlight Planet of the Apes.[11]

One script that came close to being made was written by The Twilight Zone creator Rod Serling, though it was finally rejected for a number of reasons. A prime concern was cost, as the technologically advanced ape society portrayed by Serling's script would have involved expensive sets, props, and special effects. The previously blacklisted screenwriter Michael Wilson was brought in to rewrite Serling's script and, as suggested by director Franklin J. Schaffner, the ape society was made more primitive as a way of reducing costs. Serling's stylized twist ending was retained, and became one of the most famous movie endings of all time. The exact location and state of decay of the Statue of Liberty changed over several storyboards. One version depicted the statue buried up to its nose in the middle of a jungle while another depicted the statue in pieces.[11]

To convince Fox that a Planet of the Apes film could be made, the producers shot a brief test scene from a Rod Serling draft of the script, using early versions of the ape makeup, on March 8, 1966. Charlton Heston appeared as an early version of Taylor (named Thomas, as he was in the Serling-penned drafts), Edward G. Robinson appeared as Zaius, while two then-unknown Fox contract actors, James Brolin and Linda Harrison, played Cornelius and Zira. Harrison, who was at the time the girlfriend of studio chief Richard D. Zanuck, went on to be cast as Nova. Jacobs had at first considered Ursula Andress, then screen tested Angelique Pettyjohn, and even considered doing an international talent search for the role before Harrison's casting.[12][13] Robinson wound up not joining the cast due to his declining health.

Michael Wilson's rewrite kept the basic structure of Serling's screenplay but rewrote all the dialogue and set the script in a more primitive society. According to associate producer Mort Abrahams an additional uncredited writer (his only recollection was that the writer's last name was Kelly) polished the script, rewrote some of the dialogue and included some of the more heavy-handed tongue-in-cheek dialogue ("I never met an ape I didn't like") which wasn't in either Serling or Wilson's drafts. According to Abrahams, some scenes, such as the one where the judges imitate the "see no evil, speak no evil and hear no evil" monkeys, were improvised on the set by director Franklin J. Schaffner and kept in the final film because of the audience reaction during test screenings prior to release.[14] During filming John Chambers, who designed prosthetic make-up in the film,[5] held training sessions at 20th Century-Fox studios, where he mentored other make-up artists of the film.[15]

Reception[edit]

Critical response[edit]

Planet of the Apes was met with critical acclaim and is widely regarded as a classic. It was rated one of the best films of 1968, applauded for its imagination and its commentary on a possible world turned upside down.[21][22] Pauline Kael called it "one of the most entertaining science-fiction fantasies ever to come out of Hollywood".[23] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film three out of four and called it "much better than I expected it to be. It is quickly paced, completely entertaining, and its philosophical pretensions don't get in the way".[24] Renata Adler of The New York Times wrote, "It is no good at all, but fun, at moments, to watch."[25] Arthur D. Murphy of Variety called it "an amazing film." He thought the script "at times digresses into low comedy", but "the totality of the film works very well".[26] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times wrote, "A triumph of artistry and imagination, it is at once a timely parable and a grand adventure on an epic scale."[27] Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post called it an "amusing and unusually engrossing picture."[28]

As of May 2024, the film has an 86% rating on the review aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes, based on 93 reviews with an average rating of 7.60/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Planet of the Apes raises thought-provoking questions about our culture without letting social commentary get in the way of the drama and action."[29] On Metacritic, the film has an average score of 79 out of 100 based on 14 reviews.[30] In 2008, the film was selected by Empire magazine as one of The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time.[31]