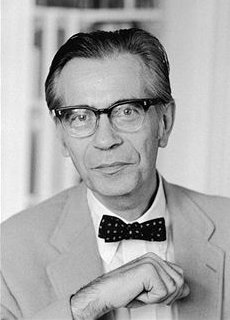

Richard Hofstadter

Richard Hofstadter (August 6, 1916 – October 24, 1970) was an American historian and public intellectual of the mid-20th century. Hofstadter was the DeWitt Clinton Professor of American History at Columbia University. Rejecting his earlier historical materialist approach to history, in the 1950s he came closer to the concept of "consensus history", and was epitomized by some of his admirers as the "iconic historian of postwar liberal consensus."[5] Others see in his work an early critique of the one-dimensional society, as Hofstadter was equally critical of socialist and capitalist models of society, and bemoaned the "consensus" within the society as "bounded by the horizons of property and entrepreneurship",[5] criticizing the "hegemonic liberal capitalist culture running throughout the course of American history".[6]

Richard Hofstadter

August 6, 1916

October 24, 1970 (aged 54)

-

Felice Swados(m. 1936; died 1945)

-

Beatrice Kevitt(m. 1947)

Pulitzer Prize (1956, 1964)

History

History of American political culture

His most widely read works are Social Darwinism in American Thought, 1860–1915 (1944); The American Political Tradition (1948); The Age of Reform (1955); Anti-intellectualism in American Life (1963); and the essays collected in The Paranoid Style in American Politics (1964). He was twice awarded the Pulitzer Prize: in 1956 for The Age of Reform, an analysis of the populism movement in the 1890s and the progressive movement of the early 20th century; and in 1964 for the cultural history Anti-intellectualism in American Life.[7] He was an elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences[8] and the American Philosophical Society.[9]

Early life and education[edit]

Hofstadter was born in Buffalo, New York, in 1916 to a Jewish father, Emil A. Hofstadter, and a German-American Lutheran mother, Katherine (née Hill), who died when Richard was ten.[10] He attended Fosdick-Masten Park High School in Buffalo. Hofstadter then studied philosophy and history at the University at Buffalo, from 1933, under the diplomatic historian Julius W. Pratt. Despite opposition from both families, he married Felice Swados (whose brother was Harvey Swados)[11] in 1936 after he and Felice spent several summers at Hunter Colony, New York, run by Margaret Lefranc, their close friend for years; they had one child, Dan.[12]

Hofstadter was raised as an Episcopalian but later identified more with his Jewish roots. Antisemitism may have cost him fellowships at Columbia and attractive professorships.[13] The Buffalo Jewish Hall of Fame lists him as one of the "Jewish Buffalonians who have made a lasting contribution to the world."[14]

In 1936, Hofstadter entered the doctoral program in history at Columbia University where his advisor Merle Curti was demonstrating how to synthesize intellectual, social, and political history based upon secondary sources rather than primary-source archival research.[15] In 1938, he became a member of the Communist Party USA, but soon became disillusioned by the Stalinist party discipline and show trials. After withdrawing from the party in August 1939 following the Hitler–Stalin Pact, he retained a critical left-wing perspective that was still obvious in American Political Tradition in 1948.[16]

Hofstadter earned his PhD in 1942. In 1944, he published his dissertation Social Darwinism in American Thought, 1860–1915. It was a commercially successful (200,000 copies) critique of late-19th-century American capitalism and its ruthless "dog-eat-dog" economic competition and Social Darwinian self-justification. Conservative critics, such as Irwin G. Wylie and Robert C. Bannister, disagreed with his interpretation.[17][18][19] The sharpest criticism of the book focused on Hofstadter's weakness as a researcher: "he did little or no research into manuscripts, newspapers, archival, or unpublished sources, relying instead primarily on secondary sources augmented by his lively style and wide-ranging interdisciplinary readings, thereby producing well-written arguments based on scattered evidence he found by reading other historians."[20]

From 1942 to 1946, Hofstadter taught history at the University of Maryland, where he became a close friend of the popular sociologist C. Wright Mills and read extensively in the fields of sociology and psychology, absorbing ideas of Max Weber, Karl Mannheim, Sigmund Freud, and the Frankfurt School. His later books frequently refer to behavioral concepts such as "status anxiety".[21][22]

Political views[edit]

Influenced by his wife, Hofstadter was a member of the Young Communist League in college, and in April 1938 he joined the Communist Party USA; he quit in 1939.[46] Hofstadter had been reluctant to join, knowing the orthodoxy it imposed on intellectuals, telling them what to believe and what to write. He was disillusioned by the spectacle of the Moscow Show Trials, but wrote: "I join without enthusiasm but with a sense of obligation.... [M]y fundamental reason for joining is that I don't like capitalism and want to get rid of it."[47] He remained anti-capitalist, writing, "I hate capitalism and everything that goes with it," but was similarly disillusioned with Stalinism, finding the Soviet Union "essentially undemocratic" and the Communist Party rigid and doctrinaire. In the 1940s, Hofstadter abandoned political causes, feeling that intellectuals were no more likely to "find a comfortable home" under socialism than they were under capitalism.[47][48]

Biographer Susan Baker writes that Hofstadter "was profoundly influenced by the political Left of the 1930s.... The philosophical impact of Marxism was so intense and direct during Hofstadter's formative years that it formed a major part of his identity crisis.... The impact of these years created his orientation to the American past, accompanied as it was by marriage, establishment of life-style, and choice of profession."[49] Geary concludes that, "To Hofstadter, radicalism always offered more of a critical intellectual stance than a commitment to political activism. Although Hofstadter quickly became disillusioned with the Communist Party, he retained an independent left-wing standpoint well into the 1940s. His first book, Social Darwinism in American Thought (1944), and The American Political Tradition (1948) had a radical point of view."[50]

In the 1940s, Hofstadter cited Beard as "the exciting influence on me".[51] Hofstadter specifically responded to Beard's social-conflict model of U.S. history, which emphasized the struggle among competing economic groups (primarily farmers, Southern slavers, Northern industrialists, and workers) and discounted abstract political rhetoric that rarely translated into action. Beard encouraged historians to search for economic belligerents' hidden self-interest and financial goals. By the 1950s and 1960s, Hofstadter had a strong reputation in liberal circles. Lawrence Cremin wrote that "Hofstadter's central purpose in writing history ... was to reformulate American liberalism so that it might stand more honestly and effectively against attacks from both left and right in a world which had accepted the essential insights of Darwin, Marx, and Freud."[52] Alfred Kazin identified his use of parody: "He was a derisive critic and parodist of every American Utopia and its wild prophets, a natural oppositionist to fashion and its satirist, a creature suspended between gloom and fun, between disdain for the expected and mad parody."[53]

In 2008, conservative commentator George Will called Hofstadter "the iconic public intellectual of liberal condescension" who "dismissed conservatives as victims of character flaws and psychological disorders—a 'paranoid style' of politics rooted in 'status anxiety.' etc. Conservatism rose on a tide of votes cast by people irritated by the liberalism of condescension."[54]

Later life[edit]

Angered by the radical politics of the 1960s, and especially by the student occupation and temporary closure of Columbia University in 1968, Hofstadter began to criticize student activist methods. His friend David Herbert Donald said, "as a liberal who criticized the liberal tradition from within, he was appalled by the growing radical, even revolutionary, sentiment that he sensed among his colleagues and his students. He could never share their simplistic, moralistic approach."[55] Brick says he regarded them as "simple-minded, moralistic, ruthless, and destructive."[56] Moreover, he was "extremely critical of student tactics, believing that they were based on irrational romantic ideas, rather than sensible plans for achievable change, that they undermined the unique status of the university, as an institutional bastion of free thought, and that they were bound to provoke a political reaction from the right."[57] Coates argues that his career saw a steady move from left to right, and that his 1968 Columbia commencement address "represented the completion of his conversion to conservatism".[58]

Despite strongly disagreeing with their political methods, he invited his radical students to discuss goals and strategy with him. He even employed one, Mike Wallace, to collaborate with him on American Violence: A Documentary History (1970); Hofstadter student Eric Foner said the book "utterly contradicted the consensus vision of a nation placidly evolving without serious disagreements."[59]

Hofstadter planned to write a three-volume history of American society. At his death, he had only completed the first volume, America at 1750: A Social Portrait (1971).

Death and legacy[edit]

Hofstadter died of leukemia on October 24, 1970, at Mount Sinai Hospital in Manhattan, at age 54.[60] He showed more interest in his research than in his teaching. In undergraduate classes, he read aloud the draft of his next book.[61] As a senior professor at a leading graduate university, Hofstadter directed more than 100 finished doctoral dissertations but gave his graduate students only cursory attention; he believed this academic latitude enabled them to find their own models of history. Among them were Herbert Gutman, Eric Foner, Lawrence W. Levine, Linda Kerber, and Paula S. Fass. Some, such as Eric McKitrick and Stanley Elkins, were more conservative than he; Hofstadter had few disciples and founded no school of history writing.[62][63]

Following Hofstadter's death, Columbia dedicated a locked bookcase of his works in Butler Library to him. When the library's physical conditions deteriorated, his widow Beatrice—who later married the journalist Theodore White—asked that it be removed.