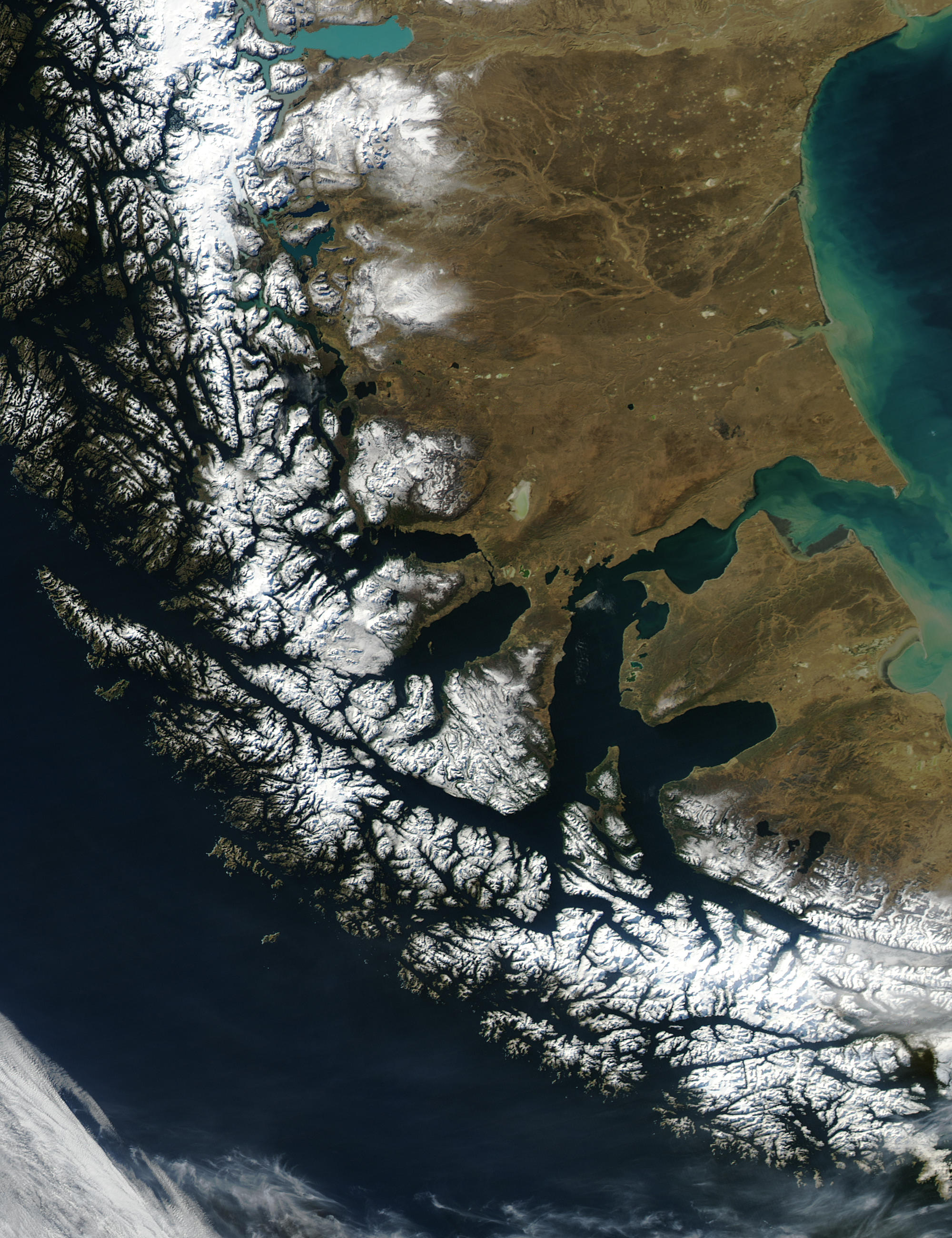

Strait of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (Spanish: Estrecho de Magallanes), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and Tierra del Fuego to the south. The strait is considered the most important natural passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The strait is approximately 570 km (310 nmi; 350 mi) long and 2 km (1.1 nmi; 1.2 mi) wide at its narrowest point. In 1520, the Spanish expedition of the Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan, after whom the strait is named, became the first Europeans to discover it.

Strait of Magellan

Magellan's original name for the strait was Estrecho de Todos los Santos ("Strait of All Saints"). The King of Spain, Emperor Charles V, who sponsored the Magellan-Elcano expedition, changed the name to the Strait of Magellan in honor of Magellan.[1]

The route is difficult to navigate due to frequent narrows and unpredictable winds and currents. Maritime piloting is now compulsory. The strait is shorter and more sheltered than the Drake Passage, the often stormy open sea route around Cape Horn, which is beset by frequent gale-force winds and icebergs.[2] Along with the Beagle Channel, the strait was one of the few sea routes between the Atlantic and Pacific before the construction of the Panama Canal.

History[edit]

[edit]

Land adjacent to the Strait of Magellan has been inhabited by indigenous Americans for at least 13,000 years. Upon their arrival to the region, they would have encountered native equines (Hippidion), the large ground sloth Mylodon, saber toothed cats (Smilodon) the extinct jaguar subspecies Panthera onca mesembrina, the bear Arctotherium, the superficially camel-like Macrauchenia, the fox-like canid Dusicyon avus and lamine camelids, including the extant vicuña and guanaco. Evidence to suggest that Mylodon, Hippidion and the lamines were hunted has been found at some sites, such as Cueva del Medio.[3]

Historically identifiable indigenous ethnic groups around the strait are the Kawésqar, the Tehuelche, the Selk'nam and Yaghan people. The Kawésqar lived on the western part of the strait's northern coast. To the east of the Kawésqar were the Tehuelche, whose territory extended to the north in Patagonia. To the south of the Tehuelche across the strait lived the Selk'nam, who inhabited the majority of the eastern portion of Tierra del Fuego. To the west of the Selk'nam were the Yaghan people, who inhabited the southernmost part of Tierra del Fuego.[4][5]

All tribes in the area were nomadic hunter-gatherers. The Tehuelche were the only non-maritime culture in the area; they fished and gathered shellfish along the coast during the winter and moved into the southern Andes in the summer to hunt.[6] The tribes of the region saw little European contact until the late 19th century. Later, European-introduced diseases decimated portions of the indigenous population.[7]

It is possible that Tierra del Fuego was connected to the mainland in the Early Holocene (c. 9000 years BP) much in the same way that Riesco Island was back then.[8] A Selk'nam tradition recorded by the Salesian missionary Giuseppe María Beauvoir relate that the Selk'nam arrived in Tierra del Fuego by land, and that the Selk'nam were later unable to return north as the sea had flooded their crossing.[9] Selk'nam migration to Tierra del Fuego is generally thought to have displaced a related non-seafaring people, the Haush that once occupied most of the main island.[10] The Selk'nam, Haush, and Tehuelche are generally thought to be culturally and linguistically related peoples physically distinct from the sea-faring peoples.[10]

According to a Selk'nam myth the strait was created along with the Beagle Channel and Fagnano Lake by slingshots falling on Earth during the fight of Taiyín with a witch who was said to have "retained the waters and the foods".[11]

Tides and weather[edit]

On the Atlantic side, the strait is characterized by semidiurnal macrotides with mean and spring tide ranges of 7.1 and 9.0 m, respectively. On the Pacific side, tides are mixed and mainly semidiurnal, with mean and spring tide ranges of 1.1 and 1.2 m, respectively.[61] There is enormous tidal energy potential in the strait.[62] The strait is prone to Williwaws, "a sudden violent, cold, katabatic gust of wind descending from a mountainous coast of high latitudes to the sea".[63][d]

Place names[edit]

The place names of the area around the strait come from a variety of languages. Many are from Spanish and English, and several are from the Ona language, adapted to Spanish phonology and spelling.[64] Examples include Timaukel (a hamlet at the east side of Tierra del Fuego), Carukinka (the end of the Almirantazgo Fjord), Anika (a channel located at 54° 7' S and 70° 30' W), and Arska (the north side of the Dawson Island).

Magellan named the strait Todos los Santos,[15] as he began his voyage through the strait on November 1, 1520, the day of "All Saints" (Todos los Santos in Spanish). Charles V renamed it Estrecho de Magallanes. Magellan named the island on the south side of the strait Tierra del Fuego, which the Yaghan people called Onaisín in the Yaghan language. Magellan also gave the name Patagones to the mainland Indians, and their land was subsequently known as Patagonia.

Bahía Cordes is named for the Dutch pirate Baltazar de Cordes.[65]

The Strait of Magellan Park, 52 km (32 mi) south of Punta Arenas, is a 250 ha (620-acre) protected area.[66]