Studio for Electronic Music (WDR)

The Studio for Electronic Music of the West German Radio (German: Studio für elektronische Musik des Westdeutschen Rundfunks) was a facility of the Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR) in Cologne. It was the first of its kind in the world, and its history reflects the development of electronic music in the second half of the twentieth century.

Founding[edit]

On 18 October 1951 a meeting was held at the then Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk in connection with a tape-recorded late-night programme about electronic music broadcast on the evening of the same day. Informed via a report on this meeting, the Intendant (General Manager) of the radio station, Hanns Hartmann, gave the green light for establishment of the studio. In this way, this date may be regarded as the founding day of the Studio für elektronische Musik.[1]

Participants in the meeting, amongst others, were Werner Meyer-Eppler, Robert Beyer, Fritz Enkel and Herbert Eimert.[2] Robert Beyer had been speaking of timbre-oriented music since as early as the 1920s. He thought the time was ripe to bring this idea to fruition. Fritz Enkel was the technician who conceptualized the first establishment of the studio. Herbert Eimert was a composer, musicologist, and journalist. In the 1920s he had published a book on the theory of atonal music, which had gotten him expelled from Franz Bölsche's composition class at the Hochschule für Musik und Tanz Köln.[3] Ever since his youth, he had stood on the side of radical musical progress and organized concerts with noise instruments. Eimert was the first director of the Studio für elektronische Musik. Werner Meyer-Eppler was a docent (lecturer) at the Institute for Phonetics and Communication Research of Bonn University. He had first employed the term electronic music in 1949, in the subtitle of one of his books, Elektrische Klangerzeugung. Elektronische Musik und synthetische Sprache. After the inventory he made in this book of electronic musical instruments developed up to that point in time, Meyer-Eppler experimentally developed in his Bonn Institute one of the basic processes of electronic music, namely the compositional creation of music directly on magnetic tape.

At the end of the above-mentioned report the availability of the men Trautwein (Düsseldorf) and Meyer-Eppler (Bonn) was pointed out. Cologne lies between Düsseldorf and Bonn. In the early 1930s Friedrich Trautwein had developed the Trautonium, one of the earliest electronic musical instruments. A version of the Trautonium, called the Monochord, was created for the studio. Meyer-Eppler carried out his experiments in Bonn with a Melochord. Harald Bode had constructed this instrument and modified it according to Meyer-Eppler's wishes. A Melochord was therefore also purchased for the Cologne studio. The Monochord and, especially, the Melochord can be understood as precursors to or an early form of the synthesizer. Synthesizers played an important role in the subsequent history of the studio.

Serial music and sine-tone composition[edit]

From this point onward Eimert actively followed the recommendation in the opening of the report by the Intendant mentioned above: "It would only be necessary to make these suitable facilities available to composers commissioned by the radio station." That is, he invited young composers who appeared suitable to him to realize the ideal of composed electronic music in the studio. Since the early 1950s, the most radical European composers had set themselves the goal of totally organizing all aspects of music. They started from the view of twelve-tone technique, but only the pitches were organized (in series of notes). The French composer Olivier Messiaen had the idea in the late 1940s of transferring the organisation of pitches onto durations, dynamics, and, conceptually, even timbres. Messiaen had two students in Paris who took up his thoughts and from then on were the best-known representatives of serial music—as it was called—Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen. In the 1970s Boulez would become the founder and director of one of the most important institutions in this field, IRCAM.

Eimert invited Stockhausen to become his assistant at the Cologne studio, and he arrived in March 1953.[9] In 1952 in Paris, at Pierre Schaeffer's Groupe de Recherches de Musique concrète, Stockhausen had already acquired some experience with various sound and tape editing processes. From this he knew that pitches, durations, and amplitudes could in fact be determined very accurately, but timbre eluded serial organisation. Soon after his arrival, Stockhausen came to regard the Monochord and Melochord (which had been purchased on the recommendation of Meyer-Eppler) as useless for the production of music that was to be organised in all its aspects, especially timbre. He turned to Fritz Enkel, the head of the calibration and testing department, and asked for a sine-wave generator or a beat-frequency oscillator capable of producing sine waves, from which Stockhausen intended to build sound spectra. Enkel was shocked, since the two recently acquired keyboard instruments, which Stockhausen was now telling him were of no use at all, had cost 120,000 Marks. Besides, Enkel told him, "It will never work!" Stockhausen responded, "Maybe you're right, but I want to try it all the same".[10]

Incorporation of natural sound material[edit]

After composing two works entirely from sine tones—Studie I and Studie II, in 1953 and 1954, respectively—Stockhausen decided to use sound material that could not be created from the devices in the studio, namely speech and song. No doubt he was influenced by Meyer-Eppler, with whom he studied phonetics and communications theory from 1954 until 1956. It was from Meyer-Eppler that Stockhausen learned about aleatory and statistical processes, and became convinced that these were necessary to avoid the sterility toward which totally organised music tends to lead.[11] For his next electronic composition, Gesang der Jünglinge (1955–56), he established connections between the different categories of human speech sounds on the one hand and those of the three main types of sound production in the studio on the other. Vowels (a, e, i, o, u and diphthongs such as ai) corresponded to sine tones and their combinations, plosive consonants (p, k, t) to pulses, and fricative consonants such as f, s, sh, and ch, to rushing noises.[12] Stockhausen on the one hand subjected the recording of a child's voice to the same manipulations as the sounds and noises produced in the studio, and on the other hand tried to approximate the latter in various degrees to the vocal sounds. He wanted to achieve a continuum between electronic and human sounds.[13] In any event, the first step had been taken towards the inclusion of materials other than sounds produced purely by electronic means. Electronic music from the Cologne studio thereby came closer conceptually to the musique concrète from Paris.

Further developments[edit]

Gottfried Michael Koenig, who assisted Stockhausen and other composers in the studio with the implementation of their pieces, was himself a composer of electronic music and, above all else, the most systematic theorist of electronic music. He did not leave things be, especially with instrumental music, which stubbornly remained in electronic music (in spite of the banishment of the monochord and melochord) now using as its "instruments" the sine-wave generator, noise generator, and pulse generator. Thinking in terms of the parameters of pitch, duration, amplitude, etc. was indeed carried over from instrumental music. The longer experiences were accumulated in the studio, the clearer it became that these terms, were no longer appropriate for complex sonic phenomena, as they emerged with the intensive use of all technical possibilities. This was also reflected in the difficulties that arose in the experiments are the notation of electronic music. If simple sine-tone composition with indication of frequencies, durations, and sound levels could still relatively simply be represented graphically, this was no longer possible for the increasingly complex pieces from the mid-1950s. Koenig wanted to create a music that was "really electronic", that is, imagined from the given technical resources of the studio, and no longer just disguised reminiscences of traditional instrumental performances. He therefore began at zero, so to speak, asking himself: what single devices and what kind of combinations between the processes amongst several devices can there be (simultaneously or, by means of tape storage, successively), and what options are available to control these processes? Practically, the pieces that he realized up to 1964 in the studio represent systematic experiments in the exploration of electronic sonorities. In the process, however, it was clear to him theoretically in 1957—therefore at the time when, in the USA, Max Mathews was making the very first experiments with sound production by a computer—that the technical capabilities of the studio were very limited. If the sine wave was not, so to speak, an indivisible element of sound, it could still be construed, with its characteristics of frequency and strength, as "instrumental". In an essay presenting some of Koenig's conclusions from his work in the studio, he spoke of the individual "amplitudes", which he wanted to determine. A sine tone is already a number of consecutive "amplitudes". Nowadays, the term "sample" refers to what Koenig meant, namely the elongation (distance from the null axis) of a signal to some point in time. Later Koenig developed a computer program that could produce episodes of "amplitudes" without regard to superordinate "instrumental" parameters.[14]

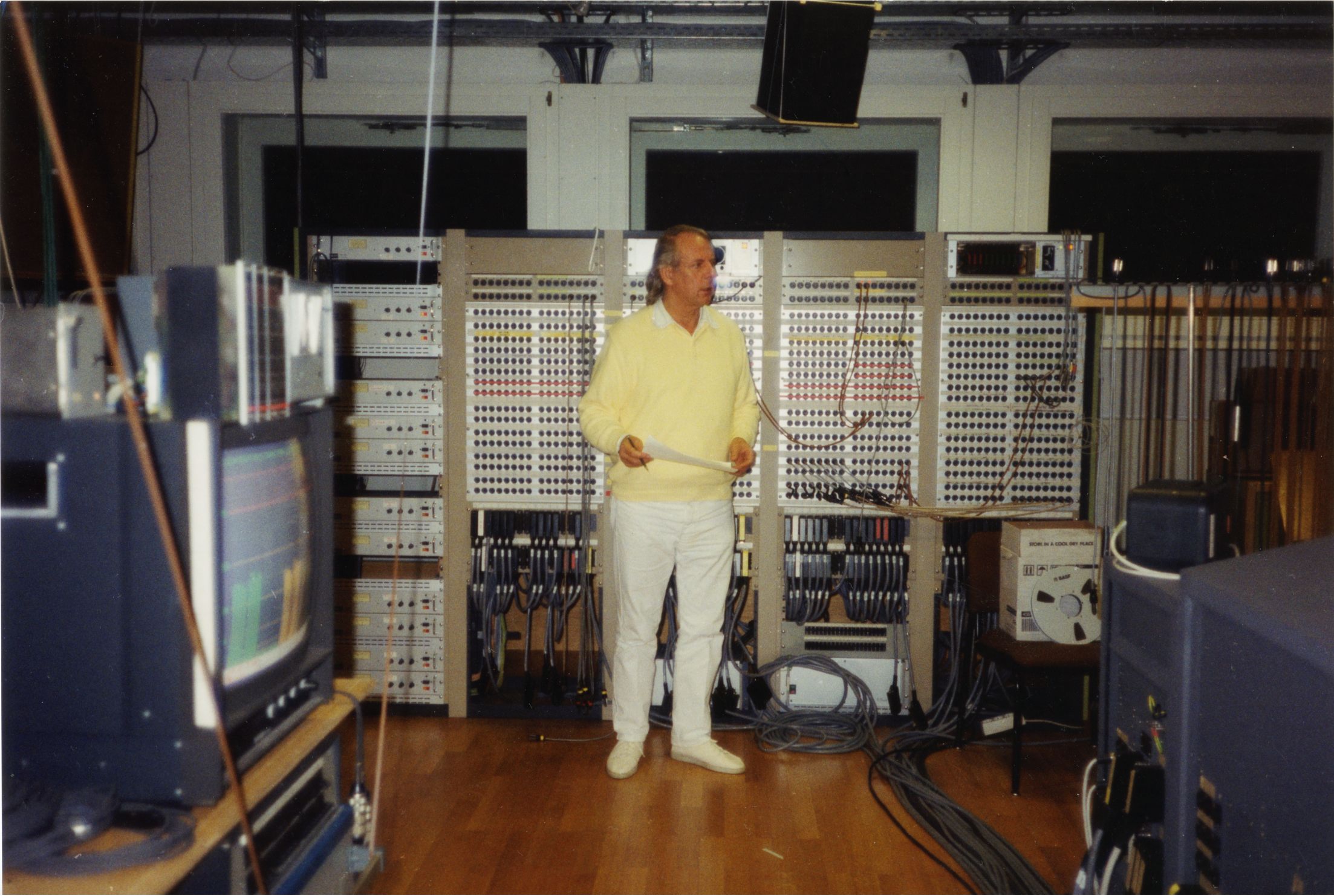

Modernising of the studio[edit]

When Herbert Eimert retired in 1962, the organisation of the studio was restructured. It was reassigned to the music division of WDR, with the intention of preventing the isolation of the technical from the musical. Eimert was officially succeeded as director of the studio by Karlheinz Stockhausen in 1963, and three years later, at the insistence of Karl O. Koch, head of the WDR Music Department, the directorship was split into two parts: artistic and administrative. Dr. Otto Tomek, who was director of the WDR new-music department, became co-ordinator between the studio and the music division.[15] Together with Gottfried Michael Koenig, Stockhausen carried out an inventory and assessment of the situation of the studio. From the compact studio, established for ready usability by Fritz Enkel a decade earlier, came an assortment of individual devices which for the most part were not intended for use together with each other. In the meantime, important steps towards a better integration of automated facilities had already been made in other studios and research institutions. In the first half of the 1960s the foundations for this integration of different devices were laid in the form of so-called voltage controlled devices in the United States. Many of the devices in the Cologne studio up until the 1960s had to be operated manually (by turning knobs, for example), while voltage control allowed automatic control of amplitude curves. For a period of three years, until mid-May 1966, compositional work in the studio had to be reduced, while it was being moved to new, larger premises. A great deal of money was invested in a new, state-of-the-art instrumentarium. It was officially re-opened on 4 December 1967.[16][17]) Nevertheless, it was not until the early 1970s that the principle of voltage control was established in the studio.

At some point before Eimert's retirement, the studio had been relocated to Sound Studio 11 on the third floor of the Broadcasting Centre. After Stockhausen took over direction of the studio, he managed with some difficulty to obtain better facilities on the fourth floor.[8]

Shift away from serial principles and further developments[edit]

The pieces that were produced in the studio from the late 1960s onward are characterized by a move away from the strict serial processes of the 1950s, especially as Gottfried Michael Koenig, the last representative of serial music, had left the studio in 1964 in order to take over the position of head of the Institute of Sonology at the Rijksuniversiteit in Utrecht. Younger composers such as Johannes Fritsch, David C. Johnson, and Mesías Maiguashca now developed the possibilities of electronic sound generation and transformation in more playful and unconventional ways. Whether produced electronically and processed, or produced mechanically, recorded by a microphone and then manipulated electronically, no sound was generally excluded from use in electronic music. Stockhausen himself had already laid the foundation in one of his longest electronic works, Hymnen (1966–67), which is based on recordings of national anthems.[18] Recordings of things like animal sounds, crowds, radio stations, construction-site noises, conversations, etc., were also used by other composers. The main constructive principle was the modulation of properties of one sound by the properties of other sounds. For example, the amplitude envelope of a recording could affect any parameter of an electronically generated sound. Mauricio Kagel placed a particular emphasis in his work on complex circuiting of the equipment (including feedback of the outputs of devices into their own inputs) in order to cause the most unpredictable results possible. Johannes Fritsch had an amplifier amplify its own noise and hum and made it to the sound material of a composition. David C. Johnson recorded noises from the Cologne main train station, among other places, and train movements from which to make the music of Telefun, in 1968.

A CD, produced by Konrad Boehmer, offers a survey of 15 the earliest pieces from the 1950s (works by Eimert, Eimert/Beyer, Goeyvaerts, Gredinger, Koenig, Pousseur, Hambraeus, Evangelisti, Ligeti, Klebe, and Brün):