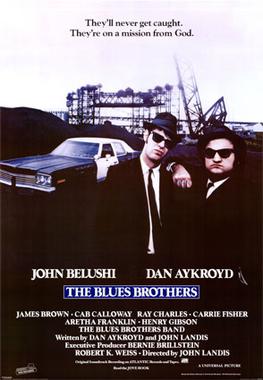

The Blues Brothers (film)

The Blues Brothers is a 1980 American musical action comedy film directed by John Landis.[4] It stars John Belushi as "Joliet" Jake Blues and Dan Aykroyd as his brother Elwood, characters developed from the recurring musical sketch "The Blues Brothers" on NBC's variety series Saturday Night Live. The script is set in and around Chicago, Illinois, where it was filmed, and the screenplay is by Aykroyd and Landis. It features musical numbers by singers James Brown, Cab Calloway, Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles and John Lee Hooker. It features non-musical supporting performances by Carrie Fisher and Henry Gibson.

The Blues Brothers

- Dan Aykroyd

- John Landis

Universal Pictures

- June 20, 1980

133 minutes[1]

United States

English

$27.5 million[2]

$115.2 million[3]

The story is a tale of redemption for paroled convict Jake and his blood brother Elwood, who set out on "a mission from God" to prevent the foreclosure of the Roman Catholic orphanage in which they were raised. To do so, they must reunite their R&B band and organize a performance to earn the $5,000 needed to pay the orphanage's property tax bill. Along the way, they are targeted by a homicidal "mystery woman", neo-Nazis, and a country and western band—all while being relentlessly pursued by the police.

Universal Studios, which won the bidding war for the film, was hoping to take advantage of Belushi's popularity in the wake of Saturday Night Live, the film Animal House, and The Blues Brothers' musical success; it soon found itself unable to control production costs. The start of filming was delayed when Aykroyd, who was new to film screenwriting, took six months to deliver a long and unconventional script that Landis had to rewrite before production, which began without a final budget. On location in Chicago, Belushi's partying and drug use caused lengthy and costly delays that, along with the destructive car chases depicted onscreen, made the film one of the most expensive comedies ever produced.

Owing to concerns that the film would fail, its initial bookings were less than half of those similar films normally received. Released in the United States on June 20, 1980, it received mostly positive reviews from critics and grossed over $115 million in theaters worldwide before its release on home video, and has become a cult classic over the years. A sequel, Blues Brothers 2000, was released in 1998. In 2020, The Blues Brothers was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[5]

Plot[edit]

Blues vocalist and petty criminal Jake Blues is released from prison after serving three years for armed robbery and is picked up by his brother Elwood in his Bluesmobile, a battered former police car. Elwood demonstrates its capabilities by jumping an open drawbridge. The brothers visit the Catholic orphanage where they were raised, and learn from Sister Mary Stigmata that it will be closed unless it pays $5,000 in property taxes. During a sermon by the Reverend Cleophus James at the Triple Rock Baptist Church, Jake has an epiphany: they can reform their band, the Blues Brothers, which disbanded while Jake was in prison, and raise the money to save the orphanage.

That night, state troopers attempt to arrest Elwood for driving with a suspended license due to 116 parking tickets and 56 moving violations. After a chase through the Dixie Square Mall, the brothers escape. The next morning, as the police arrive at the flophouse where Elwood lives, a mysterious woman detonates a bomb that demolishes the building, but leaves Jake and Elwood unharmed, saving them from arrest.

Jake and Elwood begin tracking down members of the band. Five of them are performing as "Murph and The MagicTones" at a deserted Holiday Inn lounge and quickly agree to rejoin. Another turns them down as he is the maître d' at an expensive restaurant, but the brothers threaten to become regular patrons until he relents. On their way to meet the final two band members, the brothers find the road through Jackson Park blocked by an American Nazi Party demonstration on a bridge; Elwood runs them off the bridge into the East Lagoon. The leader of the Nazi Party swears revenge. The last two band members, who now run a soul food restaurant, rejoin the band against the advice of one's wife. The reunited group obtains instruments and equipment from Ray's Music Exchange in Calumet City, and Ray, "as usual", takes an IOU.

As Jake attempts to book a gig, the mystery woman blows up the phone booth he is using; once again, he is miraculously unhurt. The band stumbles onto a gig at Bob's Country Bunker, a honky-tonk in Kokomo, Indiana. They win over the rowdy crowd, but run up a bar tab higher than their pay, and infuriate the Good Ole Boys, the country band that was booked for the gig.

Realizing that they need a big show to raise the necessary money, the brothers persuade their old agent to book the Palace Hotel Ballroom, north of Chicago. They mount a loudspeaker atop the Bluesmobile and drive around the Chicago area promoting the concert—and alerting the police, the neo-Nazis, and the Good Ole Boys of their whereabouts. The ballroom is packed with blues fans, police officers, and the Good Ole Boys. Jake and Elwood perform two songs, then sneak offstage, as the tax deadline is rapidly approaching. A record company executive offers them a $10,000 cash advance on a recording contract—more than enough to pay off the orphanage's taxes and Ray's IOU—and then tells the brothers how to slip out of the building unnoticed. As they make their escape via an electrical riser and a service tunnel, they are confronted by the mystery woman: Jake's vengeful ex-fiancée. After her volley of M16 rifle bullets leaves them once again miraculously unharmed, Jake offers a series of ridiculous excuses that she rejects, but when she looks into his eyes she takes interest in him again, allowing the brothers to escape to the Bluesmobile.

Jake and Elwood race back toward Chicago, with dozens of state and local police and the Good Ole Boys in pursuit. They elude them all with a series of improbable maneuvers, including a miraculous gravity-defying escape from the neo-Nazis. At the Richard J. Daley Center, they rush inside the adjacent Chicago City Hall building, followed by hundreds of police, state troopers, SWAT teams, firefighters, and the Illinois Army National Guard. Finding the office of the Cook County Assessor, the brothers pay the tax bill. Just as their receipt is stamped, they are arrested by the mob of law officers. In prison, the band plays "Jailhouse Rock" for the inmates.

Reception[edit]

Box office[edit]

The Blues Brothers opened on June 20, 1980, in 594 theaters. It took in $4,858,152, ranking second for that week (after The Empire Strikes Back). The film in total grossed $57,229,890 domestically and $58,000,000 in foreign box office for a total of $115,229,890. It ranked 10th at the domestic box office for the year.[3] By genre, it is the ninth-highest-grossing musical and the 10th-highest earner among comedy road movies. It ranks second, between Wayne's World and Wayne's World 2, among films adapted from Saturday Night Live sketches.[3] Landis claimed The Blues Brothers was also the first American film to gross more money overseas than it did in the U.S. Over the years, the film has retained a cult following and earned additional revenue through television, home video, and cinema reruns.[17]

Critical reception[edit]

The Blues Brothers received mostly positive reviews from critics. On Rotten Tomatoes, it has a 72% rating, based on 90 reviews, with an average rating of 7.60/10. The site's critical consensus reads: "Too over the top for its own good, but ultimately rescued by the cast's charm, director John Landis' grace, and several soul-stirring musical numbers."[6] It won the Golden Reel Award for Best Sound Editing and Sound Effects,[27] is 14th on Total Film magazine's "List of the 50 Greatest Comedy Films of All Time," 20th on Empire's list of "The 50 Greatest Comedies",[28] and 69th on Bravo's "100 Funniest Movies".[29] Metacritic gave the film a score of 60 based on 12 reviews.[30]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave The Blues Brothers three out of four, praising its energetic musical numbers and "incredible" car chases. Ebert wrote, "Belushi and Aykroyd come over as hard-boiled city guys, total cynics with a world-view of sublime simplicity, and that all fits perfectly with the movie's other parts. There's even room, in the midst of the carnage and mayhem, for a surprising amount of grace, humor, and whimsy."[31] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film a "rare four-star rating", calling it "one of the all-time great comedies" and "the best movie ever made in Chicago". He called the film "technically superb", praised it for "countering every explosion with a quiet moment", and said it "is at once a pure exercise in physical comedy as well as a marvelous tribute to the urban blues sound".[32] He ranked it eighth on his list of the ten best films of 1980.[33] Richard Corliss wrote in Time, "The Blues Brothers is a demolition symphony that works with the cold efficiency of a Moog synthesizer gone sadistic."[34]

In his Washington Post review, Gary Arnold criticized Landis for engorging "the frail plot of The Blues Brothers with car chases and crack-ups, filmed with such avid, humorless starkness on the streets of Chicago that comic sensations are virtually obliterated".[35] Janet Maslin of The New York Times criticized The Blues Brothers for shortchanging viewers on details about Jake and Elwood's affinity for African-American culture. She also took Landis to task for "distracting editing", mentioning the Soul Food diner scene in which saxophonist Marini's head is out of shot as he dances on the counter.[36] In the documentary, Stories Behind the Making of The Blues Brothers, Landis acknowledges the criticism, and says, "Everybody has his opinion", and Marini recalls the dismay he felt at seeing the completed film.

Kim Newman, writing for Empire in 2013, called The Blues Brothers "an amalgam of urban sleaze, automobile crunch and blackheart rhythm and blues" with "better music than any film had had for many years". He noted that Belushi and Aykroyd pack in their heroes: "Aretha storming through 'Think', Cab Calloway cruising through 'Minnie the Moocher', John Lee Hooker boogying through 'Boom Boom' and Ray Charles on electric piano", and observed that "the picture had revived the careers of virtually all the musicians that appeared in it", concluding, "it still sounds great and looks as good as ever through Ray Bans".[37]

On the 30th anniversary of the film's release, L'Osservatore Romano[38] (the daily newspaper of Vatican City State) wrote that the film is filled with positive symbolism and moral references that can be related to Catholicism, adding that The Blues Brothers "is a memorable film, and, judging by the facts, a Catholic one".[39]

Cult-film status[edit]

The Blues Brothers has become a staple of late-night cinema, even slowly morphing into an audience-participation show in its regular screenings at the Valhalla Cinema, in Melbourne, Australia.[40] Landis acknowledged the support of the cinema and the fans by a phone call he made to the cinema at the 10th-anniversary screening, and later invited regular attendees to make cameo appearances in Blues Brothers 2000. The fans act as the members of the crowd during the performance of "Ghost Riders in the Sky".[41]

In August 2005, a 25th-anniversary celebration for The Blues Brothers was held at Grauman's Chinese Theatre in Los Angeles.[42] Attendees included Landis, former Universal Studios executive Thom Mount, film editor George Folsey Jr., and cast members James Brown, Henry Gibson, Charles Napier, Steve Cropper, and Stephen Bishop. It featured a press conference, a panel discussion Aykroyd joined by satellite, and a screening of the film's original theatrical version. The panel discussion was broadcast directly to many other cinemas around the country.

The cult-like popularity of The Blues Brothers has also spread to non-English-language markets such as Japan; it was an inspiration for Japanese companies Studio Hibari and Aniplex, which led to the creation of the manga and anime franchise Nerima Daikon Brothers, which contain heavy references to the film.

Release[edit]

Home media[edit]

When The Blues Brothers was first screened for a preview audience, a producer demanded that Landis cut 25 minutes.[46] After trimming 15 minutes, it was released in theaters at 132 minutes. The film was first released on VHS and Betamax by MCA Videocassette Inc. in 1983; a Laserdisc from MCA Videodisc was released in the same year. It was then rereleased on VHS, Laserdisc, and Betamax in 1985 from MCA Home Video, and again in 1990 from MCA/Universal Home Video. It was also released in a two-pack VHS box set with Animal House. The original 148-minute length was restored for the "Collector's Edition" DVD and a Special Edition VHS and Laserdisc release in 1998. The DVD and Laserdisc versions included a 56-minute documentary, The Stories Behind the Making of The Blues Brothers. Produced and directed by JM Kenny (who also produced the "Collector's Edition" DVD of Animal House that year), it included interviews with Landis, Aykroyd, members of The Blues Brothers Band, producer Robert K. Weiss, editor George Folsey Jr., and others involved with the film. It includes production photographs, the theatrical trailer, production notes, and cast and filmmaker bios. The 25th Anniversary DVD release in 2005 included both the theatrical cut and the extended version.

The Blues Brothers was released on Blu-ray on July 26, 2011, with the same basic contents as the 25th Anniversary DVD. In a March 2011 interview with Ain't it Cool News, Landis said he had approved the Blu-ray's remastered transfer. On May 19, 2020, the movie was given a 4K UHD release; it has a new 4K remaster from the original negative, and the extended footage was remastered from the same archived print as well.[47]

The Blues Brothers: Original Soundtrack Recording

Other works in the franchise[edit]

In 1980, the book Blues Brothers: Private was published, designed to help flesh out the universe in which the film takes place. Private was written and designed by Belushi's wife, Judith Jacklin, and Tino Insana, a friend of Belushi's from their days at The Second City.

The video game The Blues Brothers was released in 1991. It is a platform game in which the object is to evade police and other vigilantes to get to a blues concert.

In the 1990s, Film Roman was putting an animated series based on this film in the works, which was scheduled to be released in fall 1997. The brothers of Aykroyd and Belushi (Peter and Jim) were set to take their roles as the titled characters.[65] The series was ultimately canceled because of casting complications. John Belushi's memory was dedicated in the then-upcoming sequel as his character was killed off.