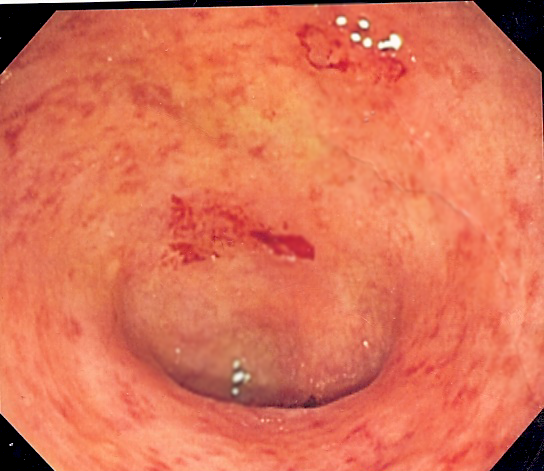

Ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is one of the two types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), with the other type being Crohn's disease.[1] It is a long-term condition that results in inflammation and ulcers of the colon and rectum.[1][7] The primary symptoms of active disease are abdominal pain and diarrhea mixed with blood (hematochezia).[1] Weight loss, fever, and anemia may also occur.[1] Often, symptoms come on slowly and can range from mild to severe.[1] Symptoms typically occur intermittently with periods of no symptoms between flares.[1] Complications may include abnormal dilation of the colon (megacolon), inflammation of the eye, joints, or liver, and colon cancer.[1][3]

Ulcerative colitis

Abdominal pain, diarrhea mixed with blood, weight loss, fever, anemia,[1] dehydration, loss of appetite, fatigue, sores on the skin, urgency to defecate, inability to defecate despite urgency, rectal pain[2]

Megacolon, inflammation of the eye, joints, or liver, colon cancer[1][3]

15–30 years or >60 years[1]

Long term[1]

Unknown[1]

Dietary changes, medication, surgery[1]

2–299 per 100,000[5]

47,400 together with Crohn's (2015)[6]

The cause of UC is unknown.[1] Theories involve immune system dysfunction, genetics, changes in the normal gut bacteria, and environmental factors.[1][8] Rates tend to be higher in the developed world with some proposing this to be the result of less exposure to intestinal infections, or to a Western diet and lifestyle.[7][9] The removal of the appendix at an early age may be protective.[9] Diagnosis is typically by colonoscopy with tissue biopsies.[1]

Several medications are used to treat symptoms and bring about and maintain remission, including aminosalicylates such as mesalazine or sulfasalazine, steroids, immunosuppressants such as azathioprine, and biologic therapy.[1] Removal of the colon by surgery may be necessary if the disease is severe, does not respond to treatment, or if complications such as colon cancer develop.[1] Removal of the colon and rectum generally cures the condition.[1][9]

History[edit]

The term ulcerative colitis was first used by Samuel Wilks in 1859. The term entered general medical vocabulary afterwards in 1888 with William Hale-White publishing a report of various cases of "ulcerative colitis".[185]

UC was the first subtype of IBD to be identified.[185]

Research[edit]

Helminthic therapy using the whipworm Trichuris suis has been shown in a randomized control trial from Iowa to show benefit in people with ulcerative colitis.[186] The therapy tests the hygiene hypothesis which argues that the absence of helminths in the colons of people in the developed world may lead to inflammation. Both helminthic therapy and fecal microbiota transplant induce a characteristic Th2 white cell response in the diseased areas, which was unexpected given that ulcerative colitis was thought to involve Th2 overproduction.[186]

Alicaforsen is a first generation antisense oligodeoxynucleotide designed to bind specifically to the human ICAM-1 messenger RNA through Watson-Crick base pair interactions in order to subdue expression of ICAM-1.[187] ICAM-1 propagates an inflammatory response promoting the extravasation and activation of leukocytes (white blood cells) into inflamed tissue.[187] Increased expression of ICAM-1 has been observed within the inflamed intestinal mucosa of ulcerative colitis patients, where ICAM-1 over production correlated with disease activity.[188] This suggests that ICAM-1 is a potential therapeutic target in the treatment of ulcerative colitis.[189]

Gram positive bacteria present in the lumen could be associated with extending the time of relapse for ulcerative colitis.[190]

A series of drugs in development looks to disrupt the inflammation process by selectively targeting an ion channel in the inflammation signaling cascade known as KCa3.1.[191] In a preclinical study in rats and mice, inhibition of KCa3.1 disrupted the production of Th1 cytokines IL-2 and TNF-α and decreased colon inflammation as effectively as sulfasalazine.[191]

Neutrophil extracellular traps[192] and the resulting degradation of the extracellular matrix[193] have been reported in the colon mucosa in ulcerative colitis patients in clinical remission, indicating the involvement of the innate immune system in the etiology.[192]

Fexofenadine, an antihistamine drug used in treatment of allergies, has shown promise in a combination therapy in some studies.[194][195] Opportunely, low gastrointestinal absorption (or high absorbed drug gastrointestinal secretion) of fexofenadine results in higher concentration at the site of inflammation. Thus, the drug may locally decrease histamine secretion by involved gastrointestinal mast cells and alleviate the inflammation.[195]

There is evidence that etrolizumab is effective for ulcerative colitis, with phase 3 trials underway as of 2016.[8][196][197][198] Etrolizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that targets the β7 subunit of integrins α4β7 and αEβ7, ultimately blocking migration and retention of leukocytes in the intestinal mucosa.[197] As of early 2022, Roche halted clinical trials for the use of etrolizumab in the treatment of ulcerative colitis.[199]

A type of leukocyte apheresis, known as granulocyte and monocyte adsorptive apheresis, still requires large-scale trials to determine whether or not it is effective.[200] Results from small trials have been tentatively positive.[201]