Wales in the early Middle Ages

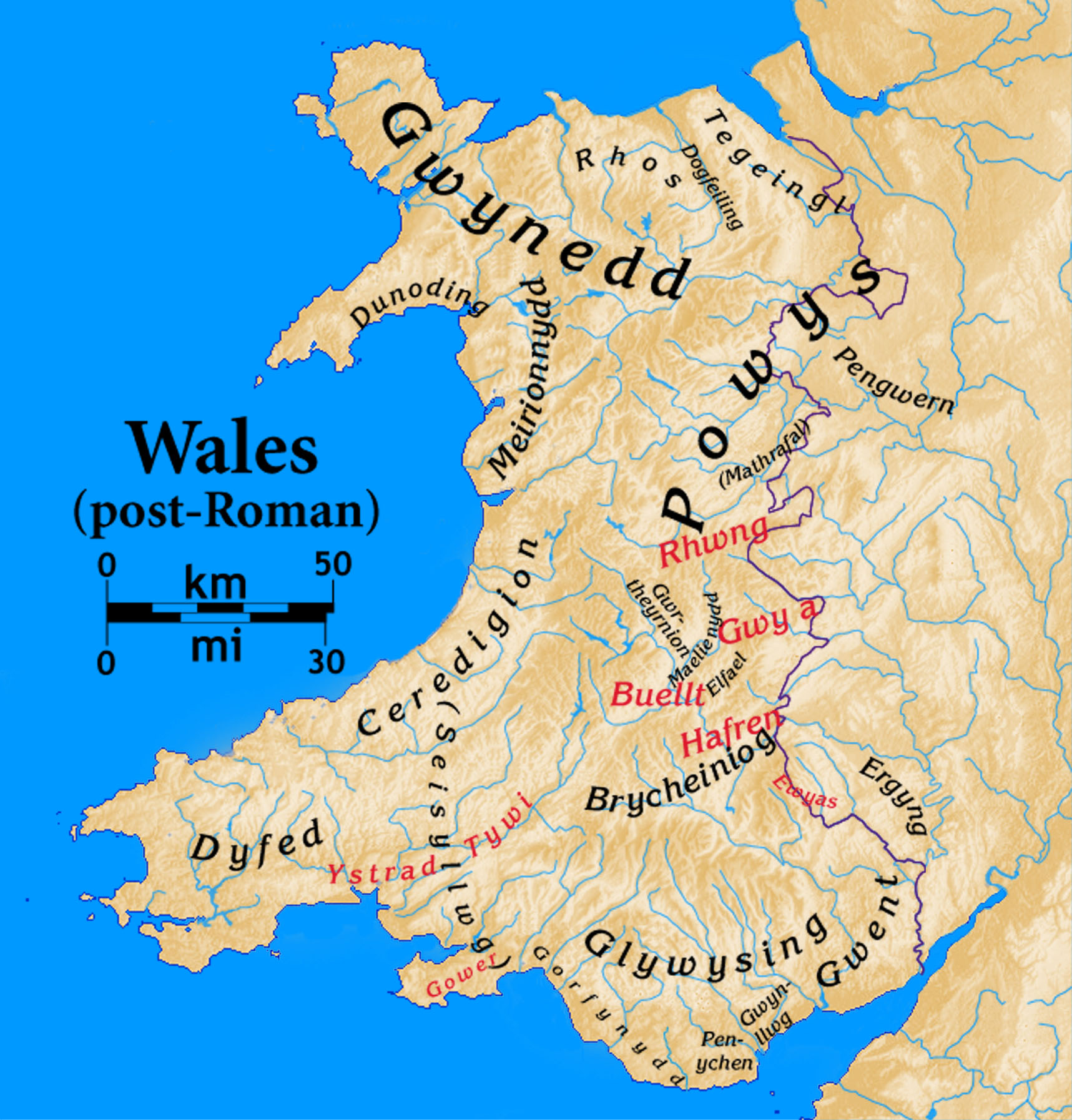

Wales in the early Middle Ages covers the time between the Roman departure from Wales c. 383 until the middle of the 11th century. In that time there was a gradual consolidation of power into increasingly hierarchical kingdoms. The end of the early Middle Ages was the time that the Welsh language transitioned from the Primitive Welsh spoken throughout the era into Old Welsh, and the time when the modern England–Wales border would take its near-final form, a line broadly followed by Offa's Dyke, a late eighth-century earthwork. Successful unification into something recognisable as a Welsh state would come in the next era under the descendants of Merfyn Frych.

Wales was rural throughout the era, characterised by small settlements called trefi. The local landscape was controlled by a local aristocracy and ruled by a warrior aristocrat. Control was exerted over a piece of land and, by extension, over the people who lived on that land. Many of the people were tenant peasants or slaves, answerable to the aristocrat who controlled the land on which they lived. There was no sense of a coherent tribe of people and everyone, from ruler down to slave, was defined in terms of his or her kindred family (the tud) and individual status (braint). Christianity had been introduced in the Roman era, and the Celtic Britons living in and near Wales were Christian throughout the era.

The semi-legendary founding of Gwynedd in the fifth century was followed by internecine warfare in Wales and with the kindred Brittonic kingdoms of northern England and southern Scotland (the Hen Ogledd) and structural and linguistic divergence from the southwestern peninsula British kingdom of Dumnonia known to the Welsh as Cernyw prior to its eventual absorption into Wessex. The seventh and eighth centuries were characterised by ongoing warfare by the northern and eastern Welsh kingdoms against the intruding Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Northumbria and Mercia. That era of struggle saw the Welsh adopt their modern name for themselves, Cymry, meaning "fellow countrymen", and it also saw the demise of all but one of the kindred kingdoms of northern England and southern Scotland at the hands of then-ascendant Northumbria.

Subsistence[edit]

Much of the arable land is in the south, southeast, southwest, on Anglesey, and along the coast. However, specifying the ancient usage of land is problematic in that there is little surviving evidence on which to base the estimates. Forest clearance has taken place since the Iron Age, and it is not known how the ancient people of Wales determined the best use of the land for their particular circumstances,[33] such as in their preference for wheat, oats, rye or barley depending on rainfall, growing season, temperature and the characteristics of the land on which they lived. Anglesey is the exception, historically producing more grain than any other part of Wales.[34]

Animal husbandry included the raising of cattle, pigs, sheep and a lesser number of goats. Oxen were kept for ploughing, asses for beasts of burden and horses for human transport.[35] The importance of sheep was less than in later centuries, as their extensive grazing in the uplands did not begin until the thirteenth century.[36] The animals were tended by swineherds and herdsmen, but they were not confined, even in the lowlands. Instead open land was used for feeding, and seasonal transhumance was practised. In addition, bees were kept for the production of honey.[37]

Society[edit]

Kindred family[edit]

The importance of blood relationships, particularly in relation to birth and noble descent, was heavily stressed in medieval Wales.[38] Claims of dynastic legitimacy rested on it, and an extensive patrilinear genealogy was used to assess fines and penalties under Welsh law. Different degrees of blood relationship were important for different circumstances, all based upon the cenedl (kindred). The nuclear family (parents and children) was especially important, while the pencenedl (head of the family within four patrilinear generations) held special status, representing the family in transactions and having certain unique privileges under the law. Under extraordinary circumstances the genealogical interest could be stretched quite far: for the serious matter of homicide, all of the fifth cousins of a kindred (the seventh generation: the patrilinear descendants of a common great-great-great-great-grandfather) were ultimately liable for satisfying any penalty.[39]

Land and political entities[edit]

The Welsh referred to themselves in terms of their territory and not in the sense of a tribe. Thus there was Gwenhwys ("Gwent" with a group-identifying suffix) and gwyr Guenti ("men of Gwent") and Broceniauc ("men of Brycheiniog"). Welsh custom contrasted with many Irish and Anglo-Saxon contexts, where the territory was named for the people living there (Connaught for the Connachta, Essex for the East Saxons). This is aside from the origin of a territory's name, such as in the custom of attributing it to an eponymous founder (Glywysing for Glywys, Ceredigion for Ceredig).[40]

The Welsh term for a political entity was gwlad ("country") and it expressed the notion of a "sphere of rule" with a territorial component. The Latin equivalent seems to be regnum, which referred to the "changeable, expandable, contractable sphere of any ruler's power".[41] Rule tended to be defined in relation to a territory that might be held and protected, or expanded or contracted, though the territories themselves were specific pieces of land and not synonyms for the gwlad.

Throughout the Middle Ages the Welsh used a variety of words for rulers, with the specific words used varying over time, and with literary sources generally using different terms than annalistic ones. Latin language texts used Latin language terms while vernacular texts used Welsh terms. Not only did the specific terms vary, the meaning of those specific terms varied over time as well.[42] For example, brenin was one of the terms used for a king in the twelfth century. The earlier, original meaning of brenin was simply a person of status.[43]

Kings are sometimes described as overkings, but the definition of what that meant is unclear, whether referring to a king with definite powers, or to ideas of someone considered to have high status.[44]