Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group that inhabited much of what is now England in the Early Middle Ages, and spoke Old English. They traced their origins to Germanic settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. Although the details are not clear, their cultural identity developed out of the interaction of these settlers with the pre-existing Romano-British culture. Over time, most of the people of what is now southern, central, northern and eastern England came to identify as Anglo-Saxon and speak Old English. Danish and Norman invasions later changed the situation significantly, but their language and political structures are the direct predecessors of the medieval Kingdom of England, and the Middle English language. Although the modern English language owes somewhat less than 26% of its words to Old English, this includes the vast majority of words used in everyday speech.[1]

This article is about Anglo-Saxon culture and society. For historical events in Anglo-Saxon England, see Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain and History of Anglo-Saxon England. For the language, see Old English. For other uses, see Anglo-Saxon (disambiguation).

Historically, the Anglo-Saxon period denotes the period in Britain between about 450 and 1066, after their initial settlement and up until the Norman Conquest.[2]

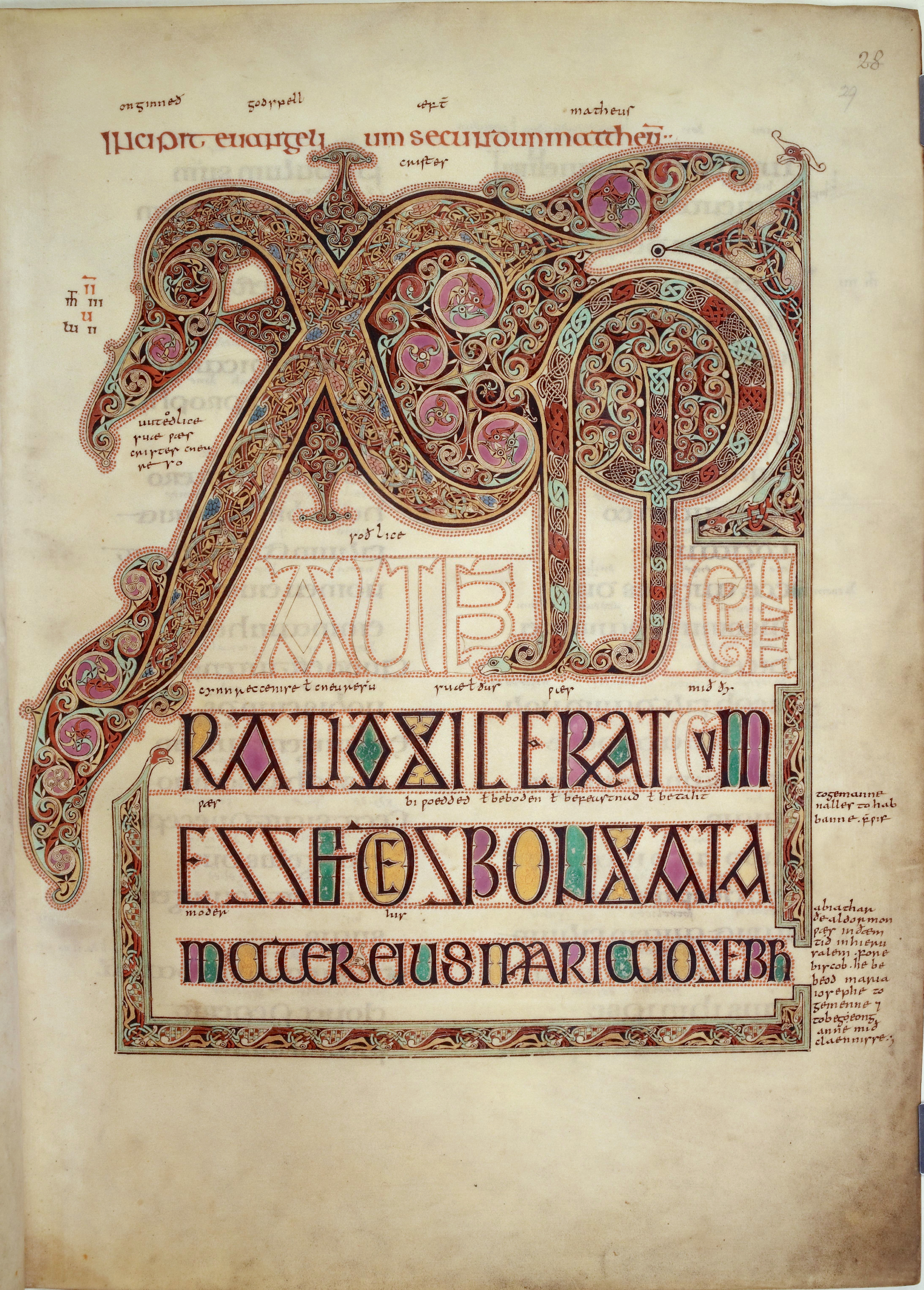

The history of the Anglo-Saxons is the history of a cultural identity. It developed from divergent groups in association with the people's adoption of Christianity and was integral to the founding of various kingdoms. Threatened by extended Danish Viking invasions and military occupation of eastern England, this identity was re-established; it dominated until after the Norman Conquest.[3] Anglo-Saxon material culture can still be seen in architecture, dress styles, illuminated texts, metalwork and other art. Behind the symbolic nature of these cultural emblems, there are strong elements of tribal and lordship ties. The elite declared themselves kings who developed burhs (fortifications and fortified settlements), and identified their roles and peoples in Biblical terms. Above all, as archaeologist Helena Hamerow has observed, "local and extended kin groups remained...the essential unit of production throughout the Anglo-Saxon period."[4] The effects persist, as a 2015 study found the genetic makeup of British populations today shows divisions of the tribal political units of the early Anglo-Saxon period.[5]

The term Anglo-Saxon began to be used in the 8th century (in Latin and on the continent) to distinguish Germanic language-speaking groups in Britain from those on the continent (Old Saxony and

Anglia in Northern Germany).[6][a] In 2003, Catherine Hills summarised the views of many modern scholars in her observation that attitudes towards Anglo-Saxons, and hence the interpretation of their culture and history, have been "more contingent on contemporary political and religious theology as on any kind of evidence."[7]

Ethnonym

The Old English ethnonym Angul-Seaxan comes from the Latin Angli-Saxones and became the name of the peoples the English monk Bede called Angli around 730[8] and the British monk Gildas called Saxones around 530.[9] Anglo-Saxon is a term that was rarely used by Anglo-Saxons themselves. It is likely they identified as ængli, Seaxe or, more probably, a local or tribal name such as Mierce, Cantie, Gewisse, Westseaxe, or Norþanhymbre. After the Viking Age, an Anglo-Scandinavian identity developed in the Danelaw.[10]

The term Angli Saxones seems to have first been used in mainland writing of the 8th century; Paul the Deacon uses it to distinguish the English Saxons from the mainland Saxons (Ealdseaxe, literally, 'old Saxons').[11] The name, therefore, seemed to mean "English" Saxons.

The Christian church seems to have used the word Angli; for example in the story of Pope Gregory I and his remark, "Non Angli sed angeli" (not English but angels).[12][13] The terms ænglisc (the language) and Angelcynn (the people) were also used by West Saxon King Alfred to refer to the people; in doing so he was following established practice.[14] Bede and Alcuin used gens Anglorum to refer to all the Anglo-Saxons: Bede referred to the people of the pre-Christian period as 'Saxons', but all becoming 'Angles' after accepting Christianity (in accordance with Pope Gregory I's use of the word Anglorum for the entire mission); Alcuin contrasted 'Saxons' with 'Angles', the former referring only to continental Saxons and the latter being associated with Britain. Bede's choice of terminology contrasted with the norm among his contemporaries, both Angle and Saxon, who collectively identified as 'Saxons' and their country as Saxonia. Aethelweard also followed Bede's usage, systematically editing all mentions of the word 'Saxon' to 'English'.[15]

The first use of the term Anglo-Saxon amongst the insular sources is in the titles for Æthelstan around 924: Angelsaxonum Denorumque gloriosissimus rex (most glorious king of the Anglo-Saxons and of the Danes) and rex Angulsexna and Norþhymbra imperator paganorum gubernator Brittanorumque propugnator (king of the Anglo-Saxons and emperor of the Northumbrians, governor of the pagans, and defender of the Britons). At other times he uses the term rex Anglorum (king of the English), which presumably meant both Anglo-Saxons and Danes. Alfred used Anglosaxonum Rex.[16] The term Engla cyningc (King of the English) is used by Æthelred. Cnut the Great, King of Denmark, England, and Norway, in 1021 was the first to refer to the land and not the people with this term: ealles Englalandes cyningc (King of all England).[17] These titles express the sense that the Anglo-Saxons were a Christian people with a king anointed by God.[18]

The indigenous Common Brittonic speakers referred to Anglo-Saxons as Saxones or possibly Saeson (the word Saeson is the modern Welsh word for 'English people'); the equivalent word in Scottish Gaelic is Sasannach and in the Irish language, Sasanach.[19] Catherine Hills suggests that it is no accident "that the English call themselves by the name sanctified by the Church, as that of a people chosen by God, whereas their enemies use the name originally applied to piratical raiders".[20]

After the Norman Conquest

Following the Norman conquest, many of the Anglo-Saxon nobility were either exiled or had joined the ranks of the peasantry.[127] It has been estimated that only about 8% of the land was under Anglo-Saxon control by 1087.[128] In 1086, only four major Anglo-Saxon landholders still held their lands. However, the survival of Anglo-Saxon heiresses was significantly greater. Many of the next generation of the nobility had English mothers and learnt to speak English at home.[129] Some Anglo-Saxon nobles fled to Scotland, Ireland, and Scandinavia.[130][131] The Byzantine Empire became a popular destination for many Anglo-Saxon soldiers, as it was in need of mercenaries.[132] The Anglo-Saxons became the predominant element in the elite Varangian Guard, hitherto a largely North Germanic unit, from which the emperor's bodyguard was drawn and continued to serve the empire until the early 15th century.[133] However, the population of England at home remained largely Anglo-Saxon; for them, little changed immediately except that their Anglo-Saxon lord was replaced by a Norman lord.[134]

The chronicler Orderic Vitalis, who was the product of an Anglo-Norman marriage, writes: "And so the English groaned aloud for their lost liberty and plotted ceaselessly to find some way of shaking off a yoke that was so intolerable and unaccustomed".[135] The inhabitants of the North and Scotland never warmed to the Normans following the Harrying of the North (1069–1070), where William, according to the Anglo Saxon Chronicle utterly "ravaged and laid waste that shire".[136]

Many Anglo-Saxon people needed to learn Norman French to communicate with their rulers, but it is clear that among themselves they kept speaking Old English, which meant that England was in an interesting tri-lingual situation: Anglo-Saxon for the common people, Latin for the Church, and Norman French for the administrators, the nobility, and the law courts. In this time, and because of the cultural shock of the Conquest, Anglo-Saxon began to change very rapidly, and by 1200 or so, it was no longer Anglo-Saxon English, but early Middle English.[137] But this language had deep roots in Anglo-Saxon, which was being spoken much later than 1066. Research has shown that a form of Anglo-Saxon was still being spoken, and not merely among uneducated peasants, into the thirteenth century in the West Midlands.[138] This was J.R.R. Tolkien's major scholarly discovery when he studied a group of texts written in early Middle English called the Katherine Group.[139] Tolkien noticed that a subtle distinction preserved in these texts indicated that Old English had continued to be spoken far longer than anyone had supposed.[138]

Old English had been a central mark of the Anglo-Saxon cultural identity. With the passing of time, however, and particularly following the Norman conquest of England, this language changed significantly, and although some people (for example the scribe known as the Tremulous Hand of Worcester) could still read Old English into the thirteenth century, it fell out of use and the texts became useless. The Exeter Book, for example, seems to have been used to press gold leaf and at one point had a pot of fish-based glue sitting on top of it. For Michael Drout this symbolises the end of the Anglo-Saxons.[140]

After 1066, it took more than three centuries for English to replace French as the language of government. The 1362 parliament opened with a speech in English and in the early 15th century, Henry V became the first monarch, since before the 1066 conquest, to use English in his written instructions.[141]

Legacy

Anglo-Saxon is still used as a term for the original Old English-derived vocabulary within the modern English language, in contrast to vocabulary derived from Old Norse and French.

Throughout the history of Anglo-Saxon studies, different narratives of the people have been used to justify contemporary ideologies. In the early Middle Ages, the views of Geoffrey of Monmouth produced a personally inspired (and largely fictitious) history that was not challenged for some 500 years. In the Reformation, Christians looking to establish an independent English church reinterpreted Anglo-Saxon Christianity. In the 19th century, the term Anglo-Saxon was broadly used in philology, and is sometimes so used at present, though the term 'Old English' is more commonly used. During the Victorian era, writers such as Robert Knox, James Anthony Froude, Charles Kingsley and Edward A. Freeman used the term Anglo-Saxon to justify colonialistic imperialism, claiming that Anglo-Saxon heritage was superior to those held by colonised peoples, which justified efforts to "civilise" them.[265][266] Similar racist ideas were advocated in 19th-century United States by Samuel George Morton and George Fitzhugh.[267] The historian Catherine Hills contends that these views have influenced how versions of early English history are embedded in the sub-conscious of certain people and are "re-emerging in school textbooks and television programmes and still very congenial to some strands of political thinking."[268]

The term Anglo-Saxon is sometimes used to refer to peoples descended or associated in some way with the English ethnic group, but there is no universal definition for the term. In contemporary Anglophone cultures outside Britain, "Anglo-Saxon" may be contrasted with "Celtic" as a socioeconomic identifier, invoking or reinforcing historical prejudices against non-English British and Irish immigrants. "White Anglo-Saxon Protestant" (WASP) is a term especially popular in the United States that refers chiefly to long-established wealthy families with mostly English ancestors. As such, WASP is not a historical label or a precise ethnological term but rather a reference to contemporary family-based political, financial and cultural power, e.g. The Boston Brahmin.

The term Anglo-Saxon is becoming increasingly controversial among some scholars, especially those in America, for its modern politicised nature and adoption by the far-right. In 2019, the International Society of Anglo-Saxonists changed their name to the International Society for the Study of Early Medieval England, in recognition of this controversy.[269]

Outside Anglophone countries, the term Anglo-Saxon and its direct translations are used to refer to the Anglophone peoples and societies of Britain, the United States, and other countries such as Australia, Canada and New Zealand – areas which are sometimes referred to as the Anglosphere. The term Anglo-Saxon can be used in a variety of contexts, often to identify the English-speaking world's distinctive language, culture, technology, wealth, markets, economy, and legal systems. Variations include the German "Angelsachsen", French "Anglo-Saxon", Spanish "anglosajón", Portuguese "Anglo-saxão", Russian "англосаксы", Polish "anglosaksoński", Italian "anglosassone", Catalan "anglosaxó" and Japanese "Angurosakuson".