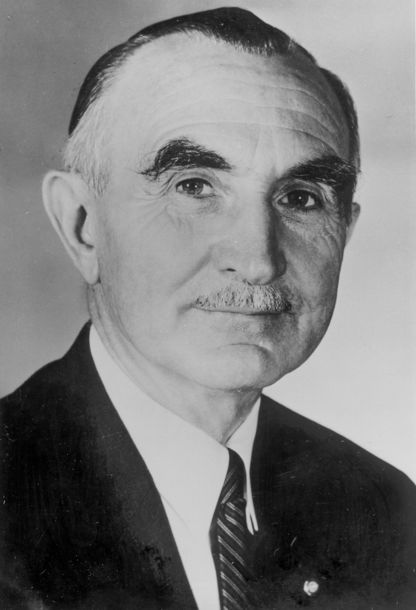

Wayne Morse

Wayne Lyman Morse (October 20, 1900 – July 22, 1974) was an American attorney and United States Senator from Oregon. Morse is well known for opposing the Democratic Party’s leadership and for his opposition to the Vietnam War on constitutional grounds.[1]

"Senator Morse" redirects here. For other uses, see Senator Morse (disambiguation).

Wayne Morse

July 22, 1974 (aged 73)

Portland, Oregon, U.S.

Republican (before 1952)

Independent (1952–1955)

Democratic (1955–1974)

3

United States

1923–1929

Born in Madison, Wisconsin, and educated at the University of Wisconsin and the University of Minnesota Law School, Morse moved to Oregon in 1930 and began teaching at the University of Oregon School of Law. During World War II, he was elected to the U.S. Senate as a Republican; he became an Independent after Dwight D. Eisenhower's election to the presidency in 1952. While an independent, he set a record for performing the third-longest one-person filibuster in the history of the Senate.[2] Morse joined the Democratic Party in February 1955, and was reelected twice while a member of that party.

Morse made a brief run for the Democratic Party's presidential nomination in 1960. In 1964, Morse was one of two senators to oppose the later-to-become-controversial Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. It authorized the president to take military action in Vietnam without a declaration of war. He continued to speak out against the war in the ensuing years, and lost his 1968 bid for reelection to Bob Packwood, who criticized his strong opposition to the war. Morse made two more bids for reelection to the Senate before his death in 1974.

United States Senator[edit]

1944 election and first term[edit]

In 1944, Morse won the Republican primary election for senator, unseating incumbent Rufus C. Holman, and then the general election that November.[5] To secure the support of the ultra-conservative wing of the Oregon Republicans in 1944, Morse had presented himself as being more right-wing than he really was, criticizing the New Deal in vitriolic terms though he also praised the wartime foreign policy of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[8]

Once in Washington, D.C., he revealed his progressive roots, to the consternation of his more conservative Republican peers.[5] Morse had intended to pull the Republican Party leftwards on the issue of union rights, a stance that put him at odds with many of the more right-wing Republicans.[9] Morse's political heroes were other progressive Republicans such as Theodore Roosevelt and Robert La Follette, and despite being a Republican admitted that he had voted in the 1944 presidential election for Franklin D. Roosevelt against the Republican candidate Thomas E. Dewey. He was greatly influenced by the "one world" philosophy of Wendell Willkie, making it clear from the onset he was an internationalist, which caused much tension with the Republican Senate Minority Leader, Robert A. Taft who favored a quasi-isolationist foreign policy.[10]

Morse believed that World War II had been partly caused by American isolationism and in one of his first speeches before the Senate, in February 1945, called on the United States to join the planned organization that would replace the League of Nations, namely the United Nations (UN).[8] As a former law professor, Morse believed very strongly in international law, and in the same speech called upon the United Nations to be an "international police organization" with such powers as to enforce via military means international law against any nation that might break it and to be given the power to prevent rich nations from economically exploiting poor nations. In another speech in March 1945, he called upon the two militarily strongest members of the "Big Three" alliance, namely the Soviet Union and the United States to work together after the war to preserve the peace and end poverty all over the world.[11] In a speech in November 1945, he declared his concern as he "watched some of the nations of the world taking a toboggan ride down the slopes of national aggrandizement and into the abyss of blind nationalism." In the same speech, he deplored the "rattling of swords and manufacturing of atomic bombs" as he called the nations of the world to stop dividing themselves into "power blocs", to take their disputes to the World Court and for the UN to have control of nuclear weapons, which he maintained were too dangerous to be entrusted to any nation.[12]

In January 1946, after President Truman delivered an address criticizing Congress and defending his proposals,[13] Morse referred to President Truman's speech as a "sad confession of the Democratic majority in Congress under the President's leadership" and called for the election of liberal Republicans in the midterm elections that year.[14] Also in January 1946, Morse called on Congress to vote on President Truman's pending legislation, citing continued delay would produce "a great economic uncertainty" and add to "reconversion slow-up". He asserted that Americans were entitled to Congress being held accountable for the passage of bills.[15] In 1946, Morse cosponsored legislation proposing a full Senate investigation into labor dispute causes, saying in March, "I think we've got to find out whether certain segments of industry are out to wreck unions."[16] He was outspoken in his opposition to the Taft–Hartley Act of 1947, which concerned labor relations.[17]

In April 1946, Morse in a speech denounced "blind national isolationism" and the tendency of many Americans to forget about their responsibilities to the "one-world community" in which they lived.[18] He charged that too many Americans had a "holier than thou" attitude towards other nations and the assumption "that if any bad faith is ever practiced within the world of nations, it is always practiced by nations other than the United States." Morse concluded that America had not always practiced "simon-pure" behavior and had economically exploited poor nations. In a speech in February 1947, Morse called Wendell Willkie his principal inspiration in foreign policy, saying that "human rights cannot be nationalized or become the monopoly of any nation" and the nations of the world must work towards "a one-world philosophy of permanent peace." Morse argued that a system of international law was needed to protect the weak nations from being dominated and exploited by strong nations. Morse strongly criticized imperialism, saying neither the Netherlands or Great Britain was a suitable ally for the United States, criticizing the Dutch for attempting to reconquer their lost colony of the Dutch East Indies (modern Indonesia) and the British for staying in the Palestine Mandate (modern Israel) against the wishes of the majority of people in Palestine, both Jewish and Arab. Morse urged both the Dutch and the British to leave the Dutch East Indies and Palestine, saying they did not have the right to rule places where they were not wanted. He supported Zionism, arguing that after the Holocaust the Jews needed their own state, and urged Britain to leave Palestine so that a Jewish state to be called Israel could be created.[19]

Though Morse had early on called for the United States to work with the Soviet Union, as the Cold War began he supported the foreign policy of President Harry S. Truman as necessary to stop Soviet expansionism. Morse voted for the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan, for the National Security Act and for the United States to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).[19]

In March 1948, Morse said he would support a tax reduction on the premise of world conditions worsening and Congress thereby being forced to recall the tax cut and admitted both his personal fear of large reductions and belief that Americans wanted tax cuts.[20]

In February 1949, during a Senate Labor committee session, Morse stated the Truman administration labor bill was not going to pass in the Senate based on how it was presently written and that "a lot of compromises must be made".[21] That year, Morse also put forward legislation that would impose national emergency strikes be handled on a case-by-case basis, the plan being turned down by the Senate on June 30 in a vote of 77 to 9. The vote was seen as a victory for supporters of the Taft–Hartley Act's provision allowing the government to get injunctions against critical strikes, though opposition was noted to have arisen from senators that did not favor this provision.[22]

In 1950, when Truman used United Nations Security Council Resolution 84 as the legal basis for committing U.S. forces to action in the Korean War, Morse supported his decision. At the time, Morse argued that Article 2 of the American constitution gave the president "very broad powers in times of emergency and national crisis" and that the resolution from the UN Security Council was binding. At the same time, Morse also warned Truman to "not get sucked" into a war in Asia and condemned him for agreeing to support France in its efforts to hold onto Vietnam.[23] Taft was opposed to using Resolution 84 as the basis for going to war in Korea, and in subsequently brought Morse around to his viewpoint that Truman acted illegally by not asking Congress for a declaration of war.[24]

In November 1950, Morse stated his belief that the incoming 82nd United States Congress would attempt revamping the Taft–Hartley Act and while admitting his continued opposition to the law, acknowledged portions of the Act that he believed could be incorporated into subsequent legislation.[25]

Re-election and independence from the Republican Party[edit]

Morse was reelected in 1950.[5] Earlier in that year, he was one of the six Senators who supported Margaret Chase Smith's Declaration of Conscience, which criticized the tactics of McCarthyism.[26]

Morse was kicked in the head by a horse in 1951. He sustained major injuries: the kick "tore his lips nearly off, fractured his jaw in four places, knocked out most of his upper teeth, and loosened several others."[27]

In protest of Dwight Eisenhower's selection of Richard Nixon as his running mate, Morse left the Republican Party in 1952.[28] Morse criticized the 1952 Republican platform with its call to repeal much of the New Deal and further felt that Eisenhower had shown cowardice by his refusal to publicly criticize Senator Joseph McCarthy, whom Morse felt was a menace to American democracy.[29] The 1952 election produced an almost evenly divided Senate; Morse brought a folding chair when the session convened, intending to position himself in the aisle between the Democrats and Republicans to underscore his lack of party affiliation.[30] Morse expected to retain certain committee memberships but was denied membership on the Labor Committee and others. He used a parliamentary procedure to force a vote of the entire Senate but lost his bid. New York's Senator Herbert Lehman offered Morse his seat on the Labor Committee, which Morse ultimately accepted.[30]

As a result of Morse's becoming an Independent, Republican control was reduced to a 48–47 majority. The deaths of nine senators, and the resignation of another, caused many reversals in control of the Senate during that session.[31]

In January 1953, after Dwight D. Eisenhower nominated Charles E. Wilson as United States Secretary of State, Morse told reporters a possible objection to the nomination could stem from the more than 10,000 General Motors shares owned by the nominee's wife.[32] In February, Morse stated that Eisenhower was partly to blame for a waste of both American manpower and money as it pertained to overseas military bases, reasoning that this had occurred while he was commander of NATO forces in Europe under the Democratic administration of President Truman.[33] In July, Morse joined nine Democrats in sponsoring a bill proposing a revision of present law to add 13,000 people to Social Security and aid benefits increases.[34] Later that month, after the death of Senate Majority Leader Robert A. Taft and questions arose of continued Republican control of the Senate, Morse confirmed his "ethical obligation" to vote with members of the party on organizational issues, citing his belief that he was acting on behalf of the American people given the Republicans gaining a majority in the 1952 elections.[35]

In 1953, Morse conducted a filibuster for 22 hours and 26 minutes protesting the Submerged Lands Act, which at the time was the longest one-person filibuster in U.S. Senate history (a record surpassed four years later by Strom Thurmond's 24-hour-18-minute filibuster in opposition of the Civil Rights Act of 1957). In 1954, with France on the verge of defeat at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, Eisenhower tentatively put forward a plan code-named Operation Vulture for American intervention. Morse spoke against U.S. intervention, saying "The American people are in no mood to contemplate the killing of thousands of American boys in Indochina" on the basis of "generalities". Morse also demanded that Congress be allowed to vote on Operation Vulture first, stating "if we get into another war, this country will be in it before Congress ever has time to declare war". After the French defeat, Morse accused Eisenhower of making the same mistakes as France did by assuming that a military solution was the best solution to Vietnamese revolutionary nationalism. Morse argued that the United States should work through the United Nations for a diplomatic solution of the Vietnam issue and to promote economic growth that would lift Vietnam out of its Third World poverty. He argued that such a policy would give the Soviet Union "clear notice" that the world community intended to protect the nations of Indochina their "right to self-government until such time as free elections can be held".[36] After the Geneva Accords which ended the Indochina War, Morse accused the Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, of having led America into "a diplomatic defeat of major significance." In September 1954, Morse voted for the United States to join the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization because it conformed to the UN Charter.[37]

In late 1954, the First Taiwan Strait Crisis began and Morse led the fight in the Senate against what became the Formosa Resolution. Morse argued that the "predated authorization" of military force that the resolution allowed violated the constitution as he noted the constitution explicitly stated that Congress had the power to declare war, and at most the president can do is merely ask Congress to declare war if he feels the situation warrants such a step. Morse proposed three amendments to the Formosa Resolution, all of which were defeated.[37]

Ruth Shipley headed the Passport Division of the United States Department of State from 1928 to 1955. She received criticism for denying passports for political reasons in the absence of due process rights but also got support as her actions were seen as opposing Communism. Linus Pauling, who had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, had his 1953 passport application that would have allowed him to accept the Prize in Sweden refused by Shipley. In rejecting his application, she cited the standard language of her office, that issuance "would not be in the best interests of the United States." but that decision was overruled.[38][39] Morse characterized her decisions as "tyrannical and capricious" due to her failures to disclose her actual reasons for the denial of such passport applications.[40] Her supporters included President Truman's Secretary of State Dean Acheson and U.S. Senator Pat McCarran of Nevada,[40] the author of the Subversive Activities Control Act of 1950, Section 6 of which made it a crime for any member of a communist organization to use or obtain a passport. In 1964, that provision was declared unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court.

In 1955, Democratic Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson persuaded Morse to join the Democratic caucus.[41]

Joining the Democratic Party[edit]

After a term as an independent, during which he campaigned heavily for Democratic U.S. Senate nominee Richard Neuberger in 1954,[42] Morse switched to the Democratic Party in February 1955. The New York Times' Saturday, February 19, 1955, issue featured a front-page photograph of Morse with the caption, "Democrats Welcome Morse to the Fold." The New York Times noted that Morse had made the switch and registered as a Democrat that Friday in his hometown of Eugene, Oregon.

In his book, Profiles in Courage, Sen. John F. Kennedy makes reference to Morse's time in the Republican and then later in the Democratic Party during Kennedy's tenure in the Senate.

When the Formosa resolution came to a vote in January 1955, Morse was one of the three senators who voted against the resolution.[37] In February 1955, during his first public appearance as a Democrat, Morse stated that the vote on the Formosa resolution would have been different if senators were not under the belief that a resolution for a ceasefire was going to be introduced the following week and that Americans did not want war with the Chinese.[43]

Despite his changes in party allegiance, for which he was branded a maverick, Morse won re-election to the United States Senate in 1956. He defeated U.S. Secretary of the Interior and former governor Douglas McKay in a hotly contested race; campaign expenditures totaled over $600,000 between the primary and general elections, a very high amount by then-contemporary standards.[44]

In March 1957 when King Saud of Saudi Arabia visited Washington and was hailed by Eisenhower as America's number one ally in the Middle East, Morse was not impressed. In a speech before the Senate, Morse stated: "Here we are, pouring by the way of gifts to that completely totalitarian state, Saudi Arabia, millions of dollars of the taxpayers' money to maintain the military forces of a dictatorship. We ought to have our heads examined!" Morse charged that Saudi Arabia's abysmal record on human rights made it an unacceptable ally.[45]

In 1957, Morse voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1957. He was the only Senator opposed to the bill who was not from the South.

In 1959, Morse opposed Eisenhower's appointment of Clare Boothe Luce as ambassador to Brazil. Morse, who had known Luce for many years,[27] chastised Luce for her criticism of Franklin D. Roosevelt.[46] Although the Senate confirmed Luce's appointment in a 79–11 vote, Luce retaliated against him.[46] In a conversation with a reporter at a party before she departed for Brazil, Luce commented that her troubles with Senator Morse were attributable to the injuries he sustained from being kicked by a horse in 1951.[47] She also remarked that riots in Bolivia might be dealt with by dividing the country up among its neighbors.[46] An immediate backlash against these remarks from Morse and other senators, and Luce's refusal to retract the remark about the horse, led to her resignation[27] just three days after her appointment.[48]

On September 4, 1959, Morse charged Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson with having attempted to form a dictatorship over other Senate Democrats and with failing to defend individual senators' rights.[49]

Feud with Richard Neuberger[edit]

Toward the end of the 1950s, Morse's relationship with Richard Neuberger, the junior senator from Oregon, deteriorated and led to much public feuding. The two had known each other since 1931, when Morse was dean of the University of Oregon law school, and Neuberger was a 19-year-old freshman. Morse befriended Neuberger and often gave him advice, and he used his rhetorical skill to successfully defend Neuberger against charges of academic cheating.[50] After the charges against him were dropped, Neuberger rejected Morse's advice to leave the university and start afresh elsewhere but instead enrolled in Morse's class in criminal law. Morse gave him a "D" in the course and, when Neuberger complained, changed the grade to an "F".[51]