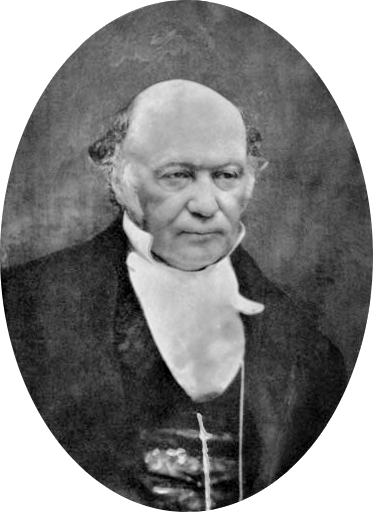

William Rowan Hamilton

Sir William Rowan Hamilton MRIA, FRAS (3/4 August 1805 – 2 September 1865)[1][2] was an Irish mathematician, astronomer, and physicist. He was the Andrews Professor of Astronomy at Trinity College Dublin, and Royal Astronomer of Ireland, living at Dunsink Observatory.

Sir William Rowan Hamilton

3 or 4 August 1805

2 September 1865 (aged 60)

Irish

British (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland)

Hamilton's principle

Hamiltonian mechanics

Hamiltonians

Hamilton–Jacobi equation

Quaternions

Biquaternions

Hamiltonian path

Icosian calculus

Nabla symbol

Versor

Coining the word 'tensor'

Coining the word 'scalar'

cis notation

Hamiltonian vector field

Icosian game

Universal algebra

Hodograph

Hamiltonian group

Cayley–Hamilton theorem

Helen Maria Bayly

William Edwin Hamilton, Archibald Henry Hamilton, Helen Eliza Amelia O'Regan, née Hamilton

Royal Medal (1835)

Cunningham Medal (1834 and 1848)

Trinity College, Dublin

Hamilton was Dunsink's third director, having worked there from 1827 to 1865. His career included the study of geometrical optics, Fourier analysis, and quaternions, the last of which made him one of the founders of modern linear algebra.[3] He has made major contributions in optics, classical mechanics, and abstract algebra. His work is fundamental to modern theoretical physics, particularly his reformulation of Newtonian mechanics. Hamiltonian mechanics including its Hamilitonian function are now central both to electromagnetism and quantum mechanics.

Early life[edit]

Hamilton was the fourth of nine children born to Sarah Hutton (1780–1817) and Archibald Hamilton (1778–1819), who lived in Dublin at 29 Dominick Street, later renumbered to 36. Hamilton's father, who was from Dublin, worked as a solicitor. By the age of three, Hamilton had been sent to live with his uncle James Hamilton, a graduate of Trinity College who ran a school in Talbots Castle in Trim, County Meath.[4][3]

Hamilton is said to have shown talent at an early age. His uncle observed that Hamilton, from a young age, had displayed an uncanny ability to acquire languages — a claim which has been disputed by some historians, who claim he had only a basic understanding of them.[5]: 207 At the age of seven, he had already made progress in Hebrew, and before he was 13, he had acquired, under the care of his uncle, a dozen languages: classical and modern European languages, Persian, Arabic, Hindustani, Sanskrit, Marathi and Malay.[6] The emphasis of Hamilton's early education on languages is attributed to the wish of his father to see him employed by the British East India Company.[7]

An expert mental calculator, the young Hamilton was capable of working out some calculations to many decimal places. In September 1813, the American calculating prodigy Zerah Colburn was being exhibited in Dublin. Colburn was 9, a year older than Hamilton. The two were pitted against each other in a mental arithmetic contest, with Colburn emerging as the clear victor.[5]: 208

In reaction to his defeat, Hamilton spent less time studying languages, and more on mathematics.[8][9] At age ten, he stumbled across a Latin copy of Euclid; and at twelve he studied Newton's Arithmetica Universalis. By age 16, he had covered much of the Principia, as well as some more recent works on analytic geometry and differential calculus.[6]

Family[edit]

While attending Trinity College, Hamilton proposed to his friend's sister, whose refusal drove the young Hamilton to depression and illness, even to the verge of suicide.[34] He proposed again in 1831 to Ellen de Vere, a sister of the poet Aubrey De Vere (1814–1902), who declined as well.[34] Hamilton eventually married Helen Marie Bayly in 1833,[34] a country preacher's daughter, and had three children with her: William Edwin Hamilton (born 1834), Archibald Henry (born 1835), and Helen Elizabeth (born 1840).[35] Hamilton's married life turned out to be difficult and unhappy as Bayly proved to be pious, shy, timid, and chronically ill.[34]

Death[edit]

Hamilton retained his faculties unimpaired to the last, and continued the task of finishing the Elements of Quaternions which had occupied the last six years of his life. He died on 2 September 1865, following a severe attack of gout.[36] He is buried in Mount Jerome Cemetery in Dublin.

Hamilton introduced, as a method of analysis, both quaternions and biquaternions, the extension to eight dimensions by the introduction of complex number coefficients. When his work was assembled in 1853, the book Lectures on Quaternions had "formed the subject of successive courses of lectures, delivered in 1848 and subsequent years, in the Halls of Trinity College, Dublin". Hamilton confidently declared that quaternions would be found to have a powerful influence as an instrument of research.

When he died, Hamilton was working on a definitive statement of quaternion science. His son William Edwin Hamilton brought the Elements of Quaternions, a hefty volume of 762 pages, to publication in 1866. As copies ran short, a second edition was prepared by Charles Jasper Joly, when the book was split into two volumes, the first appearing in 1899 and the second in 1901. The subject index and footnotes in this second edition improved the Elements accessibility.

Honours and awards[edit]

Hamilton was twice awarded the Cunningham Medal of the Royal Irish Academy.[46] The first award, in 1834, was for his work on conical refraction, for which he also received the Royal Medal of the Royal Society the following year.[47] He was to win it again in 1848.

In 1835, being secretary to the meeting of the British Association which was held that year in Dublin, Hamilton was knighted by the lord-lieutenant. Other honours rapidly succeeded, among which his election in 1837 to the president's chair in the Royal Irish Academy, and the rare distinction of being made a corresponding member of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Later, in 1864, the newly established United States National Academy of Sciences elected its first Foreign Associates, and decided to put Hamilton's name on top of their list.[48]

In literature[edit]

It is believed by some modern mathematicians that Hamilton's work on quaternions was satirized by Charles Lutwidge Dodgson in Alice in Wonderland. In particular, the Mad Hatter's tea party was meant to represent the folly of quaternions and the need to revert to Euclidean geometry.[55] In September 2022 evidence was presented to counter this suggestion, which appears to have been based on an incorrect understanding of both quaternions and their history.[56]

Family[edit]

Hamilton married Helen Bayly, daughter of Rev Henry Bayly, Rector of Nenagh, County Tipperary, in 1833; she was a sister of neighbours to the observatory.[57][15]: 108 They had three children: William Edwin Hamilton (born 1834), Archibald Henry (born 1835) and Helen Eliza Amelia (born 1840).[58] Helen stayed with her widowed mother at Bayly Farm, Nenagh for extended periods, until her mother's death in 1837. She also was away from Dunsink, staying with sisters, for much of the time from 1840 to 1842.[59] Hamilton's married life was reportedly difficult.[5]: 209 In the troubled period of the early 1840s, his sister Sydney ran his household; when Helen returned, he was happier after some depression.[15]: 125, 126