Fourier analysis

In mathematics, Fourier analysis (/ˈfʊrieɪ, -iər/)[1] is the study of the way general functions may be represented or approximated by sums of simpler trigonometric functions. Fourier analysis grew from the study of Fourier series, and is named after Joseph Fourier, who showed that representing a function as a sum of trigonometric functions greatly simplifies the study of heat transfer.

The subject of Fourier analysis encompasses a vast spectrum of mathematics. In the sciences and engineering, the process of decomposing a function into oscillatory components is often called Fourier analysis, while the operation of rebuilding the function from these pieces is known as Fourier synthesis. For example, determining what component frequencies are present in a musical note would involve computing the Fourier transform of a sampled musical note. One could then re-synthesize the same sound by including the frequency components as revealed in the Fourier analysis. In mathematics, the term Fourier analysis often refers to the study of both operations.

The decomposition process itself is called a Fourier transformation. Its output, the Fourier transform, is often given a more specific name, which depends on the domain and other properties of the function being transformed. Moreover, the original concept of Fourier analysis has been extended over time to apply to more and more abstract and general situations, and the general field is often known as harmonic analysis. Each transform used for analysis (see list of Fourier-related transforms) has a corresponding inverse transform that can be used for synthesis.

To use Fourier analysis, data must be equally spaced. Different approaches have been developed for analyzing unequally spaced data, notably the least-squares spectral analysis (LSSA) methods that use a least squares fit of sinusoids to data samples, similar to Fourier analysis.[2][3] Fourier analysis, the most used spectral method in science, generally boosts long-periodic noise in long gapped records; LSSA mitigates such problems.[4]

Fourier analysis has many scientific applications – in physics, partial differential equations, number theory, combinatorics, signal processing, digital image processing, probability theory, statistics, forensics, option pricing, cryptography, numerical analysis, acoustics, oceanography, sonar, optics, diffraction, geometry, protein structure analysis, and other areas.

This wide applicability stems from many useful properties of the transforms:

In forensics, laboratory infrared spectrophotometers use Fourier transform analysis for measuring the wavelengths of light at which a material will absorb in the infrared spectrum. The FT method is used to decode the measured signals and record the wavelength data. And by using a computer, these Fourier calculations are rapidly carried out, so that in a matter of seconds, a computer-operated FT-IR instrument can produce an infrared absorption pattern comparable to that of a prism instrument.[9]

Fourier transformation is also useful as a compact representation of a signal. For example, JPEG compression uses a variant of the Fourier transformation (discrete cosine transform) of small square pieces of a digital image. The Fourier components of each square are rounded to lower arithmetic precision, and weak components are eliminated entirely, so that the remaining components can be stored very compactly. In image reconstruction, each image square is reassembled from the preserved approximate Fourier-transformed components, which are then inverse-transformed to produce an approximation of the original image.

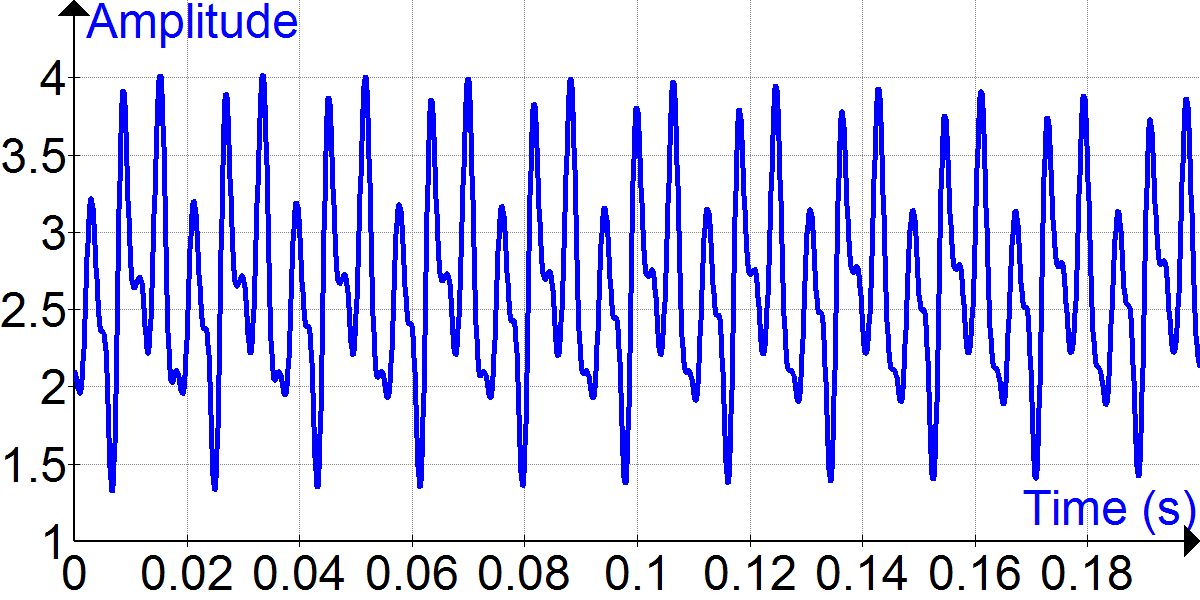

In signal processing, the Fourier transform often takes a time series or a function of continuous time, and maps it into a frequency spectrum. That is, it takes a function from the time domain into the frequency domain; it is a decomposition of a function into sinusoids of different frequencies; in the case of a Fourier series or discrete Fourier transform, the sinusoids are harmonics of the fundamental frequency of the function being analyzed.

When a function is a function of time and represents a physical signal, the transform has a standard interpretation as the frequency spectrum of the signal. The magnitude of the resulting complex-valued function at frequency represents the amplitude of a frequency component whose initial phase is given by the angle of (polar coordinates).

Fourier transforms are not limited to functions of time, and temporal frequencies. They can equally be applied to analyze spatial frequencies, and indeed for nearly any function domain. This justifies their use in such diverse branches as image processing, heat conduction, and automatic control.

When processing signals, such as audio, radio waves, light waves, seismic waves, and even images, Fourier analysis can isolate narrowband components of a compound waveform, concentrating them for easier detection or removal. A large family of signal processing techniques consist of Fourier-transforming a signal, manipulating the Fourier-transformed data in a simple way, and reversing the transformation.[10]

Some examples include:

When the real and imaginary parts of a complex function are decomposed into their even and odd parts, there are four components, denoted below by the subscripts RE, RO, IE, and IO. And there is a one-to-one mapping between the four components of a complex time function and the four components of its complex frequency transform:[11]

From this, various relationships are apparent, for example:

Fourier transforms on arbitrary locally compact abelian topological groups[edit]

The Fourier variants can also be generalized to Fourier transforms on arbitrary locally compact Abelian topological groups, which are studied in harmonic analysis; there, the Fourier transform takes functions on a group to functions on the dual group. This treatment also allows a general formulation of the convolution theorem, which relates Fourier transforms and convolutions. See also the Pontryagin duality for the generalized underpinnings of the Fourier transform.

More specific, Fourier analysis can be done on cosets,[21] even discrete cosets.