Young Americans

Young Americans is the ninth studio album by the English musician David Bowie, released on 7 March 1975 through RCA Records. A departure from the glam rock style of previous albums, the record showcased Bowie's interest in soul and R&B. Music critics have described the sound as blue-eyed soul; Bowie himself labelled the album's sound "plastic soul".

This article is about the album by David Bowie. For other uses, see Young Americans (disambiguation).Young Americans

7 March 1975

August 1974 – January 1975

- Sigma Sound, Philadelphia

- Record Plant, New York City

- Electric Lady, New York City

40:00

- David Bowie

- Harry Maslin

- Tony Visconti

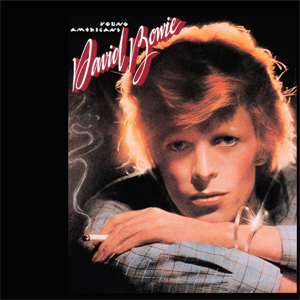

Recording sessions began at Sigma Sound Studios in Philadelphia in August 1974, after the first leg of his Diamond Dogs Tour. The record was produced by Tony Visconti, and includes a variety of musicians, such as the guitarist Carlos Alomar, who became one of Bowie's most frequent collaborators, and the backing vocalists Ava Cherry, Robin Clark and then-unknown singer Luther Vandross. As the tour continued the setlist and design began to incorporate the influence of the new material. The recording sessions continued at the Record Plant in New York City at the tour's end. A collaboration between Bowie and John Lennon yielded a cover of Lennon's Beatles song "Across the Universe" and "Fame" during a January 1975 session at Electric Lady Studios, produced by Harry Maslin. The album's cover artwork is a back-lit photograph of Bowie taken by Eric Stephen Jacobs.

Young Americans was Bowie's breakthrough in the US, reaching the top 10 on the Billboard chart; the single "Fame" became Bowie's first number one hit. Bowie continued developing its sound on Station to Station (1976). Young Americans has received mixed critical reviews on release and in later decades; Bowie himself had mixed feelings about the album. The album proved influential. Bowie was one of the first white artists of the era to overtly engage with black musical styles; other British artists followed suit. The album has been reissued multiple times with outtakes, and was remastered in 2016 as part of the Who Can I Be Now? (1974–1976) box set.

Artwork[edit]

For the album cover artwork, Bowie initially wanted to commission Norman Rockwell to create a painting but retracted the offer when he heard that Rockwell would need at least six months to do the job. According to Pegg, another rejected idea was a full-length portrait of Bowie in a "flying suit" and white scarf, standing in front of an American flag and raising a glass. The final cover photo, a back-lit and airbrushed photo of Bowie, was taken in Los Angeles on 30 August 1974 by photographer Eric Stephen Jacobs.[1] Jacobs took inspiration from a similar photo he took of choreographer Toni Basil for the September 1974 cover of After Dark magazine.[9] Using that photo, Craig DeCamps designed the final cover at RCA Records' New York City office.[65][66] Sandford calls it one of the "classic" album covers.[28]

Legacy[edit]

Subsequent events[edit]

Bowie continued developing the funk and soul of Young Americans, with electronic and German krautrock influences, for his next studio album, Station to Station,[99][100] recorded in Los Angeles from September to November 1975 and released in January 1976.[101][102] Songs from the Young Americans period that foreshadowed the album's direction included "Win", "Can You Hear Me?" and "Who Can I Be Now?"[5][103] Station to Station continued Bowie's run of commercial success, reaching number three in the US.[104] However, his cocaine use continued throughout 1975; he later admitted he had almost no recollection of recording Station to Station.[100] After completing the Isolar Tour in May 1976, he moved to Europe to rid himself of his drug addiction.[105][106]

Commentators have acknowledged Young Americans as Bowie's first album that he performed as himself rather than as a persona.[37][107][18] Sandford believed that Bowie showed maturity by not featuring Ziggy Stardust, which secured his breakthrough into the US market.[28] Pegg says the album turned Bowie from "a mildly unsavoury cult artist to a chat-show friendly showbiz personality" in the US.[1] Bowie, however, expressed varying statements about the album throughout his lifetime.[38] In late 1975, he described it as "the phoniest R&B I've ever heard. If I ever would have got my hands on that record when I was growing up I would have cracked it over my knee."[42] He further described it as "a phase" in a 1976 interview with Melody Maker.[108] He later reversed his stance in 1990, telling Q magazine: "I shouldn't have been quite so hard on myself, because looking back it was pretty good white, blue-eyed soul [and] it was quite definitely one of the best bands I ever had."[109]

Influence[edit]

Young Americans has been called one of Bowie's most influential records.[71] With the album, Bowie was one of the first mainstream white artists to embrace black musical styles,[28] paving the way for other artists to engage in similar styles.[1] Daryl Easlea summarised in Record Collector: "While all rock'n'roll was based on white men's appropriation of black popular music, very few artists had embraced the form wholesale, to the point of using the same studios and musicians, as Bowie [did]."[6] Buckley commented that it brought fans of both glam rock and soul together in the wake of the disco era.[71] In subsequent years, artists who experimented with funk and soul after Bowie included Elton John, Roxy Music, Rod Stewart, the Rolling Stones, Bee Gees, Talking Heads, Spandau Ballet, Japan and ABC.[1][6] Bowie was also referenced directly by George Clinton in the Parliament song "P. Funk (Wants to Get Funked Up)" (1976) and in the film Saturday Night Fever (1977).[6] Clinton also used a modified version of the "Fame" instrumental for Parliament's "Give Up the Funk (Tear the Roof off the Sucker)" (1976), while James Brown used "Fame"'s riff verbatim for "Hot (I Need to Be Loved, Loved, Loved)" (1975).[32] In 2016, Joe Lynch of Billboard argued that "Fame" and Young Americans as a whole served as an influence not only on other funk artists such as Clinton but also early hip hop artists and the West Coast G-funk genre of the early 1990s.[110]