2017 United Kingdom general election

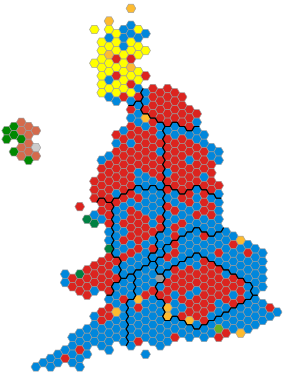

The 2017 United Kingdom general election was held on Thursday 8 June 2017, two years after the previous general election in 2015; it was the first since 1992 to be held on a day that did not coincide with any local elections.[2] The governing Conservative Party remained the largest single party in the House of Commons but lost its small overall majority, resulting in the formation of a Conservative minority government with a confidence and supply agreement with the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) of Northern Ireland.[3]

All 650 seats in the House of Commons

326[n 1] seats needed for a majority

The Conservative Party, which had governed as a senior coalition partner from 2010 and as a single-party majority government from 2015, was led by Theresa May as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. It was defending a working majority of 17 seats against the Labour Party, the official opposition led by Jeremy Corbyn. It was the first general election to be contested by either May or Corbyn as party leader; May had succeeded David Cameron following his resignation as prime minister the previous summer, while Corbyn had succeeded Ed Miliband after he resigned following Labour's failure to win the general election two years earlier.

Under the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 an election had not been due until May 2020, but Prime Minister May's call for a snap election was ratified by the necessary two-thirds vote in the House of Commons on 19 April 2017. May said that she hoped to secure a larger majority to "strengthen [her] hand" in the forthcoming Brexit negotiations.[4]

Opinion polls had consistently shown strong leads for the Conservatives over Labour. From a 21-point lead, the Conservatives' lead began to diminish in the final weeks of the campaign. The Conservative Party returned 317 MPs—a net loss of 13 seats relative to 2015—despite winning 42.4% of the vote (its highest share of the vote since 1983), whereas the Labour Party made a net gain of 30 seats with 40.0% (its highest vote share since 2001 and its highest increase in vote share between two general elections since 1945). It was the first election since 1997 in which the Tories made a net loss of seats or Labour a net gain of seats. The election had the closest result between the two major parties since February 1974 and resulted in their highest combined vote share since 1970. The Scottish National Party (SNP) and the Liberal Democrats, the third- and fourth-largest parties, both lost vote share; media coverage characterised the result as a return to two-party politics.[5] The SNP, which had won 56 of the 59 Scottish seats at the previous general election in 2015, lost 21. The Liberal Democrats made a net gain of four seats. UKIP, the third-largest party in 2015 by number of votes, saw its share of the vote reduced from 12.6% to 1.8% and lost its only seat.

In Wales, Plaid Cymru gained one seat, giving it a total of four seats. The Green Party retained its sole seat, but its share of the vote declined. In Northern Ireland, the DUP won 10 seats, Sinn Féin won seven, and Independent Unionist Sylvia Hermon retained her seat. The Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) and Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) lost all their seats.

Negotiation positions following the UK's invocation of Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union in March 2017 to leave the EU were expected to feature significantly in the campaign, but did not as domestic issues took precedence instead. The campaign was interrupted by two major terrorist attacks: Manchester and London Bridge; thus, national security became a prominent issue in its final weeks.

The outcome of the election would have significant implications for the Brexit negotiations, and led the Parliament of the United Kingdom into a period of protracted deadlock which would eventually bring about another general election two and a half years later.

Campaign[edit]

Background[edit]

Prior to the calling of the general election, the Liberal Democrats gained Richmond Park from the Conservatives in a by-election, a seat characterised by its high Remain vote in the 2016 EU referendum.[104] The Conservatives held the safe seat of Sleaford and North Hykeham in December 2016.[105] In by-elections on 23 February 2017, Labour held Stoke-on-Trent Central but lost Copeland to the Conservatives, the first time a governing party had gained a seat in a by-election since the Tories took Mitcham and Morden in 1982.[106]

The general election came soon after the Northern Ireland Assembly election on 2 March. Talks on power-sharing between the DUP and Sinn Féin had failed to reach a conclusion, with Northern Ireland thus facing either another Assembly election, or the imposition of direct rule. The deadline was subsequently extended to 29 June.[107]

Local elections in England, Scotland and Wales took place on 4 May. These saw large gains by the Conservatives, and large losses by Labour and UKIP. Notably, the Conservatives won metro mayor elections in Tees Valley and the West Midlands, areas traditionally seen as Labour heartlands.[108] Initially scheduled for 4 May, a by-election in Manchester Gorton was cancelled; the seat was contested on 8 June along with all the other seats.[109][110]

On 6 May, a letter from Church of England Archbishops Justin Welby and John Sentamu stressed the importance of education, housing, communities and health.[111]

All parties suspended campaigning for a time in the wake of the Manchester Arena bombing on 22 May.[112] The SNP had been scheduled to release their manifesto for the election but this was delayed.[113] Campaigning resumed on 25 May.[114]

Major political parties also suspended campaigning for a second time on 4 June, following the London Bridge attack.[115] UKIP chose to continue campaigning.[116] There were unsuccessful calls for polling day to be postponed.[116]

Media coverage[edit]

In contrast to the 2015 general election, in which smaller parties received more media coverage than usual, coverage during the 2017 election focused on the two main political parties, Labour and the Conservatives[288] (84% of the politicians featured in newspapers, and 67% on TV, were Conservative or Labour), with Conservatives sources receiving the most coverage and quotation, particularly in the print media (the margin of difference between Conservative and Labour sources was 2.1 points on TV and 9.6 points in newspapers).[289] The five most prominent politicians were Theresa May (Cons) (30.1% of news appearanced), Jeremy Corbyn (Lab) (26.7%), Tim Farron (Lib Dem) (6.8%), Nicola Sturgeon (SNP) (3.7%), and Boris Johnson (Cons) (3.6%).[289] The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) received next to no coverage during the campaign[288] (0.4% of appearances) but were prominent in coverage after the election.[289]

Social media was used during the election campaign by both political parties. Labour's key success in the election campaign was partly attributed to the use of social media. It was shown that Labour, who took the strategy of going for 'positive posting', like focusing on social improvement, welfare and public services was favoured over the Conservatives who had focused on negative topics like campaigning on security and terrorism.[290] The findings showed that over the course of the election campaign, Labour had outperformed the Conservatives and Corbyn's personal Facebook page significantly outweighed May's Facebook page by 5 million to nearly 800,000.[291]

Newspapers were partisan in their coverage and generally took an attacking editorial line, providing negative coverage of one or more parties they opposed rather than advocating for the party they endorsed,[289] with Labour receiving the most negative coverage.[289][292] Mick Temple, professor of Journalism and Politics at Staffordshire University, characterised the negativity Corbyn and Labour received during this election as more hostile than that which Ed Miliband and Labour received during the 2015 general election.[293] Jeremy Corbyn was portrayed as a coward,[294] and he and his closest allies were accused of being terrorist sympathizers.[295][288][296][297][294] During the election period, BBC Question Time host David Dimbleby said Jeremy Corbyn had not had 'a fair deal at the hands of the press' and that he was more popular than the media made him out to be.[298] An exception, when the Conservative Party received more negative coverage than Labour, was during the third week of the campaign, when the Conservatives released their manifesto, proposed a controversial social welfare policy (which became known as the "dementia tax") and subsequently made a U-turn on the proposal.[289] When newspaper circulation size is accounted for, the Conservative Party was the only party to receive a positive evaluation overall from the press.[289] It was endorsed by newspapers that had an 80% share of the national Sunday press audience (the five Sunday newspapers endorsing the Conservatives had a daily circulation of more than 4 million)[281] and 57% of the national daily press[299] (a combined circulation of 4,429,460[266]).

One national Sunday newspaper (the Sunday Mirror), endorsed Labour, with two others endorsing tactical voting against the Conservative (these three titles, with a daily circulation of under 1 million, had a share of 20% of the Sunday press audience),[281] and 11% of the national daily press[299] (namely, The Guardian and the Daily Mirror; a combined circulation of 841,010[266]). On this metric, 'Conservative partisanship was the most salient voice in the British national press'.[297] When newspapers' articles were measured by their positivity and negativity towards and against the parties running in the election, The Sun, The Daily Telegraph, the Daily Express and the Daily Mail provided support for the Conservatives and The Guardian and the Daily Mirror provided support for the Labour party.[289] However, few Guardian or Mirror election-related editorials called for a vote for Labour, and even fewer endorsed Corbyn – many articles in left-wing papers criticised him, or he was ignored.[297] While the collective voice of the right-wing papers were (four times) stronger in their support for the Conservatives than the left-wing were of Labour, on the whole they were similar to the left in their negativity towards, or avoidance of, the leader of their endorsed party.[297] Only the Daily Express gave Theresa May unreserved support.[297] After the election, the press turned on Theresa May,[300] who had run on a campaign that platformed her as a 'strong and stable' leader, and they described her as 'weak and wobbly', 'robotic', the 'zombie prime minister', and a 'dead woman walking'.[301]

Broadcast media, by giving airtime directly to Jeremy Corbyn and his policy ideas, was seen as playing a significant role during the election in presenting him as someone less frightening that the newspapers had presented him and more engaging than Theresa May.[302][303][304][305][306] The BBC has been criticised for its coverage during the election campaign. For example, right-wing papers The Sun and the Daily Mail complained that the audience at the BBC run leaders' debate was pro-Corbyn, and the Daily Mail asked why the topic of immigration, one of the Conservatives favoured issues, was barely mentioned; and right-wing websites Breitbart London and Westmonster said BBC coverage on Brexit was pro-EU.[307] Left-wing websites, like The Canary, The Skwawkbox and Another Angry Voice complained that the BBC was pro-Tory and anti-Corbyn.[307] According to analysts, a bias was evident during Jeremy Paxman's leaders debates, with 54% of airtime devoted to Conservative issues and 31% to Labour's.[299] In an episode of Have I Got News for You aired during the campaign period, Ian Hislop, editor of Private Eye, suggested the BBC was biased in favour of the Conservatives.[308] The BBC's political editor Laura Kuenssberg particularly received criticism for her election coverage.[307] During the election the BBC circulated a 2015 report of Kuenssberg's (on Corbyn's views on 'shoot to kill' policy) that had been censured by the BBC Trust for its misleading editing; on the final day of the election the BBC acknowledged that the clip was subject to a complaint that had been upheld by the Trust.[299]

As during the 2015 election, although less than then (−12.5%), most media coverage (32.9%) was given to the workings of the electoral process itself (e.g., electoral events, opinion polls, 'horse race' coverage, campaign mishaps).[289] During the first two weeks of campaigning, members of the public, interviewed in vox pops,[309] made up a fifth to almost a half of all sources in broadcast news.[288] While in the first two weeks of the election period policy made up less than half of all broadcast coverage,[288] over the whole campaign policy received more coverage in all media than during the previous election,[289] particularly after manifestos were published in the third week, when close to eight in ten broadcast news items were primarily about policy issues.[288] Policy around Brexit and the EU receiving most coverage overall (10.9%), and national events that happened during the campaign period (namely, the terrorist attacks on Manchester Arena and in the area of London Bridge), along with controversies over Trident, brought policy issues around defence and security to the fore (7.2%).[289][310][311]

From the start of the campaign, commentators predicted a landslide victory for the Conservatives.[312][288][313] After the results were in and the Conservatives had won by a much smaller margin, on air Channel 4's Jon Snow said, "I know nothing, we the media, the pundits and experts, know nothing".[288] A number of newspaper columnists expressed similar sentiments.[314] Some analysts and commentators have suggested the gap between the newspapers' strong support, and the public's marginal support, for the Conservatives in this election indicates a decline in the influence of print media, and/or that in 2017's election social media played a decisive role (perhaps being the first election in which this was the case[310][315]).[316][300][301][293][317][311][318][319][320] Some website and blog content, like that produced by The Canary and Another Angry Voice, gained as much traffic as many mainstream media articles[320][305] and went more viral than mainstream political journalism.[300][307] The London Economic had the most shared election-related article online during the campaign.[321] Others urge caution,[296] stressing that the traditional press still have an importance influence on how people vote.[322][296][312] In a YouGov poll, 42% of the general public said that TV was most influential in helping them choose, or confirming their choice in, whom to vote for; 32% said newspapers and magazines; 26%, social media; and 25%, radio.[323] 58% of people surveyed also thought that the social media had diminished the influence of newspapers.[323]