African Romance

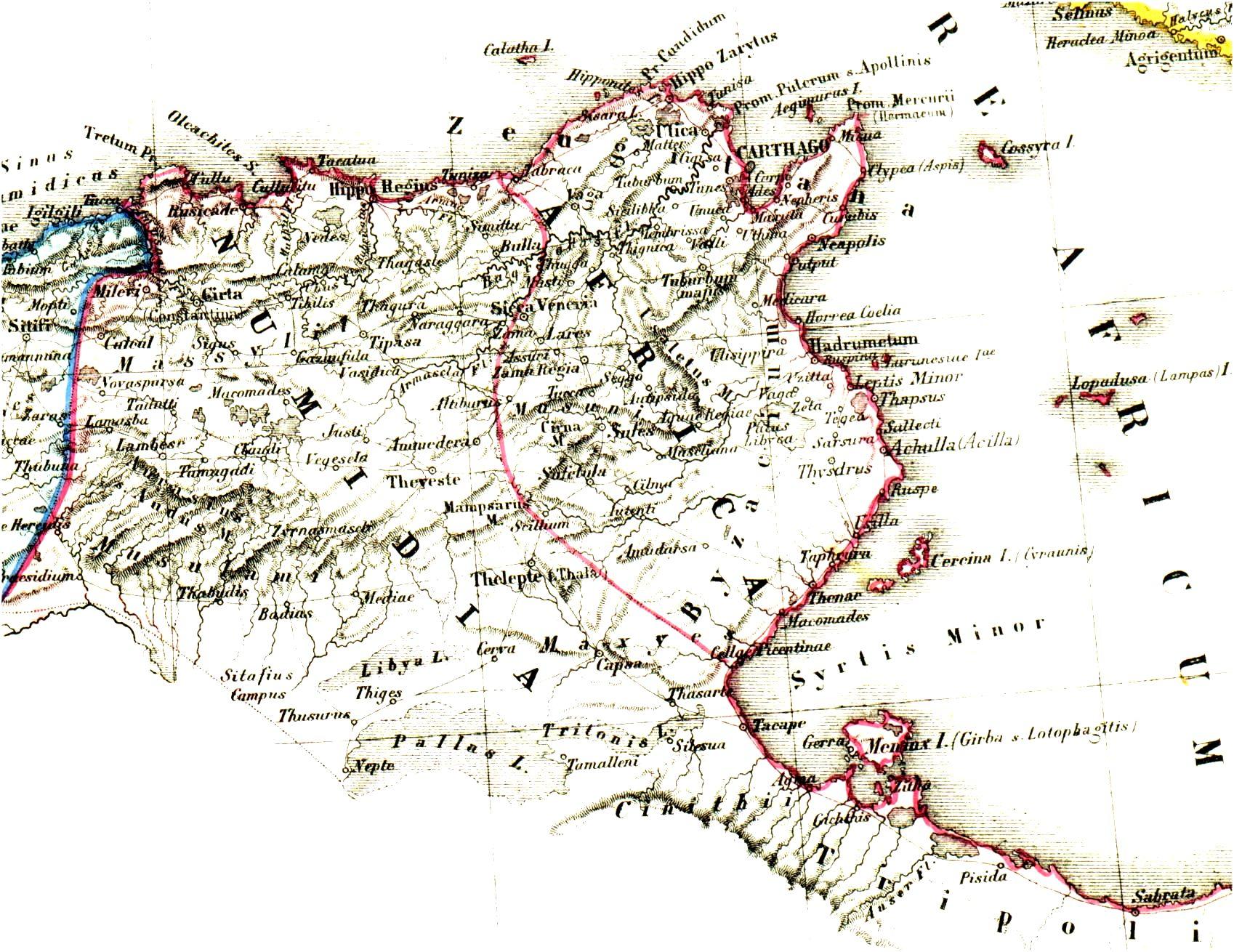

African Romance or African Latin is an extinct Romance language that was spoken in the various provinces of Roman Africa by the African Romans under the later Roman Empire and its various post-Roman successor states in the region, including the Vandal Kingdom, the Byzantine-administered Exarchate of Africa and the Berber Mauro-Roman Kingdom. African Romance is poorly attested as it was mainly a spoken, vernacular language.[1] There is little doubt, however, that by the early 3rd century AD, some native provincial variety of Latin was fully established in Africa.[2]

This article is about an extinct Romance language once spoken in modern-day Northern Africa. For modern Romance languages or dialects of those languages spoken in Africa, see African French and Portuguese language in Africa.African Romance

c. 1st–15th century AD(?)

-

Italic

- Latino-Faliscan

- Latin

- Romance

- Southern Romance?

- African Romance

- Southern Romance?

- Romance

- Latin

- Latino-Faliscan

None (mis)

None

After the conquest of North Africa by the Umayyad Caliphate in 709 AD, this language survived through to the 12th century in various places along the North African coast and the immediate littoral,[1] with evidence that it may have persisted up to the 14th century,[3] and possibly even the 15th century,[2] or later[3] in certain areas of the interior.