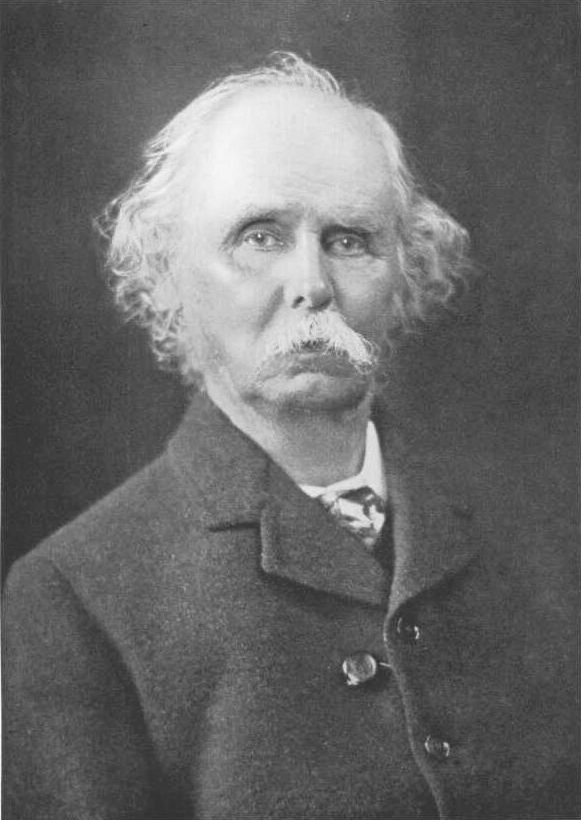

Alfred Marshall

Alfred Marshall FBA (26 July 1842 – 13 July 1924) was an English economist, and was one of the most influential economists of his time. His book Principles of Economics (1890) was the dominant economic textbook in England for many years. It brought the ideas of supply and demand, marginal utility, and costs of production into a coherent whole.[2] He is known as one of the founders of neoclassical economics.[3]

For other people named Alfred Marshall, see Alfred Marshall (disambiguation).

Alfred Marshall

26 July 1842

13 July 1924 (aged 81)

St John's College, Cambridge

- Father of microeconomics and welfare economics

- Founder of neoclassical economics

- Principles of Economics (1890)

- Marshallian scissors

- Internal and external economies

- Marshall–Lerner condition

Life and career[edit]

Marshall was born at Bermondsey in London, second son of William Marshall (1812–1901), clerk and cashier at the Bank of England, and Rebecca (1817–1878), daughter of butcher Thomas Oliver, from whom, on her mother's death, she inherited property.[4] William Marshall was a devout strict Evangelical,[5] "author of an Evangelical epic in a sort of Anglo-Saxon language of his own invention which found some favour in its appropriate circles" and of a tract titled Men's Rights and Women's Duties. There are scholars who note that this strict upbringing wielded strong influence on Marshall's work such as how he favored the doctrines of philosophical idealism.[5]

Marshall had two brothers and two sisters; a cousin was the economist Ralph Hawtrey. The Marshalls were a West Country clerical family; Marshall's great-great-grandfather was "the Reverend William Marshall, half-legendary Herculean parson of Devonshire", famous for "twisting horseshoes with his hands" to scare "local blacksmiths into fearing that they blew their bellows for the devil".[6][7] Marshall grew up in Clapham and was educated at the Merchant Taylors' School[8] and St John's College, Cambridge, where he demonstrated an aptitude in mathematics, achieving the rank of Second Wrangler in the 1865 Cambridge Mathematical Tripos.[9][10] Marshall experienced a mental crisis that led him to abandon physics and switch to philosophy. He began with metaphysics, specifically "the philosophical foundation of knowledge, especially in relation to theology".[11] Metaphysics led Marshall to ethics, specifically a Sidgwickian version of utilitarianism; ethics, in turn, led him to economics, because economics played an essential role in providing the preconditions for the improvement of the working class.

He saw that the duty of economics was to improve material conditions,[2] but such improvement would occur, Marshall believed, only in connection with social and political forces. His interest in Georgism, liberalism, socialism, trade unions, women's education, poverty and progress reflect the influence of his early social philosophy on his later activities and writings.

Marshall was elected in 1865 to a fellowship at St John's College at Cambridge, and became lecturer in the moral sciences in 1868. He was Mary Paley's professor of political economy at Cambridge; they became a couple and were married in 1877, forcing Marshall to leave his position as a Fellow of St John's College, Cambridge. He became the first principal at University College, Bristol, which was the institution that later became the University of Bristol, again lecturing on political economy and economics.

In 1885 he became professor of political economy at Cambridge, where he remained until his retirement in 1908. Over the years he interacted with many British thinkers including Henry Sidgwick, W.K. Clifford, Benjamin Jowett, William Stanley Jevons, Francis Ysidro Edgeworth, John Neville Keynes and John Maynard Keynes. Marshall founded the Cambridge School which paid special attention to increasing returns, the theory of the firm, and welfare economics; after his retirement leaderships passed to Arthur Cecil Pigou and John Maynard Keynes.

Later career[edit]

Marshall served as president of the first day of the 1889 Co-operative Congress.[19]

Over the next two decades he worked to complete the second volume of his Principles, but his unyielding attention to detail and ambition for completeness prevented him from mastering the work's breadth. The work was never finished and many other, lesser works he had begun work on – a memorandum on trade policy for the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the 1890s, for instance – were left incomplete for the same reasons.

His health problems had gradually grown worse since the 1880s, and in 1908 he retired from the university. He hoped to continue work on his Principles but his health continued to deteriorate and the project had continued to grow with each further investigation. The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 prompted him to revise his examinations of the international economy and in 1919 he published Industry and Trade at the age of 77. This work was a more empirical treatise than the largely theoretical Principles, and for that reason it failed to attract as much acclaim from theoretical economists. In 1923, he published Money, Credit, and Commerce, a broad amalgam of previous economic ideas, published and unpublished, stretching back a half-century.

Final years, death and legacy[edit]

From 1890 to 1924 he was the respected father of the economic profession and to most economists for the half-century after his death, the venerable grandfather. He had shied away from controversy during his life in a way that previous leaders of the profession had not, although his even-handedness drew great respect and even reverence from fellow economists, and his home at Balliol Croft in Cambridge had no shortage of distinguished guests. His students at Cambridge became leading figures in economics, including John Maynard Keynes and Arthur Cecil Pigou. His most important legacy was creating a respected, academic, scientifically founded profession for economists in the future that set the tone of the field for the remainder of the 20th century.

Marshall died aged 81 at his home in Cambridge and is buried in the Ascension Parish Burial Ground.[20] The library of the Department of Economics at Cambridge University (The Marshall Library of Economics), the Economics society at Cambridge (The Marshall Society)[21] as well as the University of Bristol Economics department are named after him. His archive is available for consultation by appointment at the Marshall Library of Economics.[22]

His home, Balliol Croft, was renamed Marshall House in 1991 in his honour when it was bought by Lucy Cavendish College, Cambridge.[23]

Alfred Marshall's wife was Mary Paley, an economist who was one of the first women students at Cambridge and a lecturer at Newnham College.[24] She continued to live in Balliol Croft until her death in 1944; her ashes were scattered in the garden. The couple had no children.[25]