Anointing

Anointing is the ritual act of pouring aromatic oil over a person's head or entire body.[1]

"Anointed" redirects here. For the savior and liberator in Abrahamic religions, see Messiah. For the character in the Buffy the Vampire Slayer series, see Anointed One (Buffyverse).

By extension, the term is also applied to related acts of sprinkling, dousing, or smearing a person or object with any perfumed oil, milk, butter, or other fat.[2] Scented oils are used as perfumes and sharing them is an act of hospitality. Their use to introduce a divine influence or presence is recorded from the earliest times; anointing was thus used as a form of medicine, thought to rid persons and things of dangerous spirits and demons which were believed to cause disease.

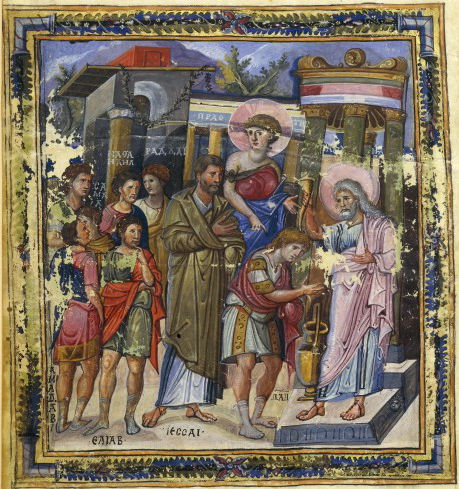

In present usage, "anointing" is typically used for ceremonial blessings such as the coronation of European monarchs. This continues an earlier Hebrew practice most famously observed in the anointings of Aaron as high priest and both Saul and David by the prophet Samuel. The concept is important to the figure of the Messiah or the Christ (Hebrew and Greek[3] for "The Anointed One") who appear prominently in Jewish and Christian theology and eschatology. Anointing—particularly the anointing of the sick—may also be known as unction; the anointing of the dying as part of last rites in the Catholic church is sometimes specified as "extreme unction".

Name[edit]

The present verb derives from the now obsolete adjective anoint, equivalent to anointed.[4] The adjective is first attested in 1303,[n 1] derived from Old French enoint, the past participle of enoindre, from Latin inung(u)ere,[6] an intensified form of ung(u)ere 'to anoint'. It is thus cognate with "unction".

The oil used in a ceremonial anointment may be called "chrism", from Greek χρῖσμα (khrîsma) 'anointing'.[7]