Banat of Craiova

The Banat of Craiova or Banat of Krajowa (German: Banat von Krajowa; Romanian: Banatul Craiovei), also known as Cisalutanian Wallachian Principality (Latin: Principatus Valachiae Cisalutanae) and Imperial Wallachia (German: Kaiserliche Walachei; Latin: Caesarea Wallachia;[1] Romanian: Chesariceasca Valahie), was a Romanian-inhabited province of the Habsburg monarchy. It emerged from the western third of Wallachia, now commonly known as Oltenia, which the Habsburgs took in a preceding war with the Ottoman Empire—in tandem with the Banat of Temeswar and Serbia. It was a legal successor to the Great Banship of Craiova, with the Wallachian Gheorghe Cantacuzino as its native leader, or Ban. Over the following years, native rule was phased out, and gave way to a direct administration. This provided the setting for Germanization of the bureaucratic elite, introducing the governing methods of enlightened absolutism and colonialism.

Banat of CraiovaBanat von Krajowa

Banatul Craiovei

Banatul Craiovei

Krajowa (Craiova)

34,346 families (officially registered)

Georgius Schramm von Otterfels

Joachim Czeyka von Olbramowitz

J. H. Dietrich

Franciscus Salhausen

21 July 1718

22 February 1719

27 April 1729

November 1737

18 September 1739

Habsburg rule over Oltenia only lasted two decades, which fit within the reign of just one Austrian Emperor (and titular "Prince of Cisalutanian Wallachia"), Charles VI (1711–1740). Its steady encroachment on the privileges of native boyars, as well as its added pressures on the serfs and the free peasants, were highly unpopular, undermining Austrophile positions in Wallachia as a whole. The period witnessed collective tax resistance and internal migration, in an effort to conceal the total number and location of contributors. Charles VI and the Serbian Orthodox Bishops in Belgrade took charge of the Wallachian Diocese of Râmnic, curbing its traditional privileges while allowing it to maintain cultural autonomy. Some timid steps were taken toward Catholicizing Oltenia, with Catholic Bulgarians as the main proxies. Despite being pressured from above, Râmnic Bishops were able to expand their influence into southern Transylvania, providing it with support against the spread of Greek Catholicism.

Popular resistance required a steady adaptation of the administrative apparatus, which included more accurate censuses, relief of some feudal obligations, and heavy penalties for tax offenders. The process was directly supervised by Austrian officials, including Franz Paul von Wallis in the 1730s. It was cut short by an unexpected Ottoman reconquest in late 1737, which brought another devastation of Oltenia, but also witnessed the reestablishment of self-rule by the Romanians. "Imperial Wallachia" formally ended in 1739, when the Ottoman Empire recovered Serbia and Oltenia (which was returned to Wallachia) after the Treaty of Belgrade.

The claim to Oltenia was formally revived during the 1770s by Joseph II, but died out a decade later. The Banat of Temeswar, which became home to a sizable community of Romanian Oltenian and Bulgarian refugees, was kept by the Habsburg monarchy and its successors until 1918. Though rejected by the mass of the people, the Habsburg experiment in Oltenia produced some lasting changes, with some institutions maintained in place by Wallachian Prince Constantine Mavrocordatos. Austrian influence, which introduced the region to organized guilds and a postal system, also provided Wallachians with a linguistic template for modernization and re-Latinization.

History[edit]

Austrian conquest[edit]

The autonomous Banship of Craiova covered a quadrilateral western third of Wallachia, located between the Southern Carpathians to the north, the Danube to the south and west, and the Olt River (Alutus in Latin; hence "Cisalutanian") to the east. Since the 15th century, Wallachia, including its Oltenian subdivision, had been subjugated by the Ottoman Empire (its neighbor to the south), participating as such in the Ottoman–Habsburg wars. During the 17th century, members of the Wallachian boyardom, especially those linked with the Cantacuzino family, began looking to the Habsburgs as potential liberators of the country.[2] The period included several episodes in which Wallachia was declared a Habsburg fief. One such early case was on 7 January 1543, when Radu Paisie, the Prince of Wallachia, nominally attached his country to the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary.[3] In June 1598, during an episodic emancipation from Ottoman vassalage, Prince Michael the Brave and his Postelnic Andronic Cantacuzino (both of whom had served as Bans) submitted Wallachia to the Holy Roman Empire.[4] The Great Turkish War of 1683 saw Prince Șerban Cantacuzino and his Wallachian military forces fighting on the Ottoman side; however, they made a public show of their reluctance, and privately celebrated Habsburg Austria's victory in the Battle of Vienna.[5]

During the 1680s, the Habsburgs were on the offensive, and only their forced participation in the War of the Reunions prevented Wallachia from being conquered at that stage.[6] In August 1716, the Battle of Petrovaradin marked a turning point in the fourth Austro-Turkish War: the Habsburg monarchy chased the Ottoman Army out of Central Europe, and stood to occupy both Wallachia and Moldavia. As a result of this, the Sublime Porte reduced autonomy for Wallachia by introducing a new political elite, the Greek-speaking Phanariotes; Nicholas Mavrocordatos, a Phanariote known for having pacified Moldavia, was brought in to reign as titular Prince of Wallachia.[7] Seeking to undermine the Austrian advance, Ottoman commanders and the Budjak Tatars staged the mass deportation and enslavement of Wallachian peasants—Oltenians were reportedly over-represented in this exodus, as 35,000 evacuees from a total 80,000.[8] The problem was compounded by internal flight, with many more villagers fleeing for safety into the Oltenian forests and the Parâng Massif.[9] As many as 273 Oltenian villages and hamlets were left deserted, from a total 741; 190 of these ghost villages were located in the exposed southern fields.[10] The events notably witnessed the ransacking of Brâncovenești boyar estates, including their manor in Brâncoveni (which had been one of Oltenia's two major military buildings).[11]

As early as March 1716, the Austrians could count on support from an inner faction of Wallachian boyars. Formed around Spătar Radu Leurdeanu Golescu, it regarded Mavrocordatos as a "tyrant".[12] Answering to boyar requests for help, the Habsburg general Stephan von Steinville sent in some hundreds of his soldiers, which, also in August 1716, routed a 3,000-strong Wallachian army at Orșova—according to chronicler Radu Popescu, these troops were secretly opposed to Mavrocordatos, and did not put up a fight. Oltenia was taken whole when the Wallachian Serdar, Cornea Brăiloiu, defected to the enemy, guiding more Austrian troops through the Vulcan Pass and into Târgu Jiu.[13] Some Oltenian boyars were soon co-opted by Prince Eugene of Savoy and his invasion force: Postelnic Ștefan Pârșcoveanu led 200 Habsburg soldiers in battle against the Mavrocordatos troops, at Bengești-Ciocadia.[14] An Austrian force under Stephan Dettine von Pivoda ventured out of Oltenia and into Pitești, then took the Wallachian capital, Bucharest on 14 November, capturing the Prince; during this episode, most Wallachian forces had been diverted to Oltenia, with Popescu invested as Ban.[15] Despite earning support from the Wallachian assembly, which declared itself subject to Emperor Charles VI on 28 November, the Austrians were not confident about establishing a bridgehead in Muntenia, and withdrew immediately after to Mărgineni and Câmpulung.[16]

In December 1716, the Ottomans retook Bucharest and placed John Mavrocordatos on the throne. On 24 February, he obtained from the Austrians recognition as Prince of Wallachia, which was understood to mean only Muntenia; the new ruler also agreed to pay Charles VI a lump tribute in "bags of gold".[17] During the following period, refugee boyars sent Charles several petitions asking for Oltenia to be kept as an autonomous part of the Empire, with its own Voivode, namely Gheorghe Cantacuzino. During this campaign, they expressed alarm that Oltenia would be incorporated with Transylvania, which was in the process of losing its autonomy.[18] The boyar delegations were also mandated to discuss the exclusion of Phanariotes and other Greeks from the table of ranks, which formed the basis of boyar privilege and revenue. They were encouraged in this by Damaschin Voinescu, the Orthodox Bishop of Râmnic, who described Greeks as "betrayers and destroyers of countries".[19]

Heraldists from the Holy Roman Empire had traditionally used a lion to represent kleine Walachey ("Little Wallachia"), which, from the 16th century, generally meant the Craiova Banship. These were attributed arms, which had no local correspondent, and may have originally stood for "Dacia" or "Cumania"; the lion was apparently never used by the Bans, and neither was it taken up by the Austrian administration.[203] Before 1718, local Bans used some symbols of their own, which are attested, but not described, by contemporary sources. In the mid 17th century, Mareș Băjescu had a grapă, adecă steag bănesc ("grapă, which is to say a Ban's flag") brought in for his ceremonial investiture in Craiova.[204] Historian Ion Donat reports that the region also had its own badge, separate from the Wallachian seal, and its own flag, at least as early as the 1500s.[205] Theologian Irineu Popa argues that flags used by the Bans showed Demetrius of Thessaloniki, who is still the patron saint of Craiova.[206]

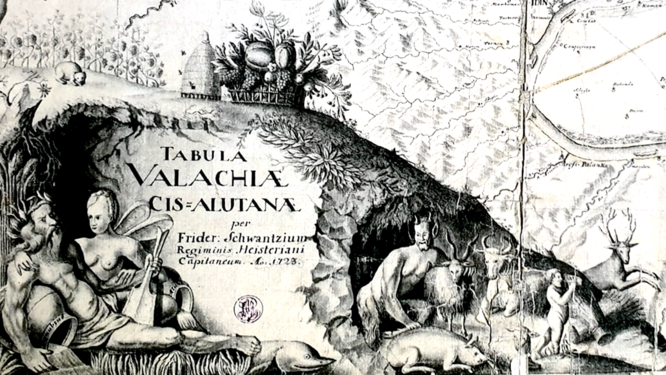

In its early years, Imperial Wallachia used a variant of the standard Wallachian seal;[207] this symbol can be found in the bottom right corner of Schwantz von Springfels' 1723 map.[208] Also in 1723, this all-Wallachian emblem was replaced with a complex seal depicting the double-headed Reichsadler displaying the Wallachian bird.[209] According to a roll of arms created by Radu Cantacuzino, the same arrangement was used as the personal arms of his brother, Ban Gheorghe.[210] The Reichsadler, a familiar presence on the Austrian border markers, became known locally as Zgripțor. The same term was used as a by-word for Habsburg rule and its officials.[211]

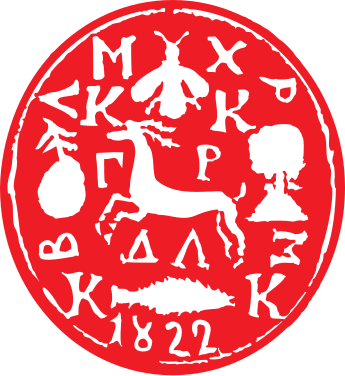

In their effort to modernize the administration, Austrian authorities banned the usage of private insignia on official documents. Instead, they regulated corporate heraldic seals for each of the five Oltenian counties. These referred to the main economic contribution of each Oltenian subdivision: Dolj had a fish; Gorj—a deer; Mehedinți—a beehive; Romanați—an ear of corn; and Vâlcea—a fruit-bearing tree.[212] According to historian Dan Cernovodeanu, these symbols, though not attested in writing before 1719 (and first appearing in visual form as a companion to Schwantz's 1723 map), were locally made, and likely predated the Austrian occupation.[213] They were also largely preserved into the later seals of Oltenian Bani and Caimacami, into the early 19th century.[214]