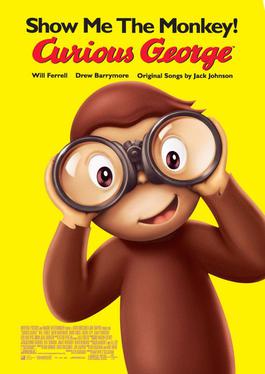

Curious George (film)

Curious George is a 2006 animated adventure film[1] based on the book series written by H. A. Rey and Margret Rey. It was directed by Matthew O'Callaghan (in his theatrical feature directorial debut), written by Ken Kaufman and produced by Ron Howard, David Kirschner, and Jon Shapiro. Featuring the voices of Will Ferrell, Drew Barrymore, David Cross, Eugene Levy, Joan Plowright, and Dick Van Dyke, it tells the story of how the Man with the Yellow Hat, a tour guide at a museum, first befriended a curious monkey named George and started going on adventures with him around the city while attempting to save the museum from closure.

Curious George

Ken Kaufman

- Ken Kaufman

- Mike Werb

- Ron Howard

- David Kirschner

- Jon Shapiro

Julie Rogers

- February 10, 2006 (United States)

- May 25, 2006 (Germany)

87 minutes[3]

English

$50 million[3]

$69.9 million[3]

It is the first theatrically-released animated film from Universal Pictures since 1995's Balto, the first theatrical animated film from Universal Animation Studios (making this Universal's first in-house theatrical animated film), and the first animated film from Imagine Entertainment. The film had languished in development hell at Imagine Entertainment since at least 1992, but it is possible that it was conceived years before. The film employs a notable blend of traditional animation and CGI scenery and objects that make up 20% of its environment. The soundtrack was composed by Heitor Pereira and features several songs by musician Jack Johnson.

Curious George was released in the United States by Universal Pictures on February 10, 2006. It was met with generally positive reviews, but only grossed $70 million worldwide against a budget of $50 million. Despite being a box office bomb, Curious George made $48 million in DVD sales in the home market. It received five sequels, although all but one of them were released as direct-to-video films.

Plot[edit]

A happy and mischievous but lonely orphaned monkey lives in the jungle of Africa. Meanwhile, Ted is a tour guide living in New York City, who works at the Bloomsberry Museum and gives weekly presentations to schoolteacher Maggie Dunlop and her students. His boss and the museum owner, Mr. Bloomsberry, informs Ted that the museum is losing money and will have to close. Mr. Bloomsberry's son Junior wants to tear down the museum and replace it with a commercial parking lot. Ted impulsively volunteers to travel to Africa to bring back an ancient 40-foot-tall idol, the Lost Shrine of Zagawa, hoping that it will attract visitors. Junior gets jealous of Ted's constant praise from Mr Bloomsberry that he burns half the map to sabotage the exhibition. Ted is outfitted with a bright yellow suit and hat and boards a cargo ship to Africa.

In the jungle, Ted finds the idol with the help of his guide, Edu, but it is only three inches tall. He sends a photograph of it to the museum, but the photograph's angle leads Mr. Bloomsberry to believe that the idol is even larger than he thought. Ted encounters the monkey living there and gives him his yellow hat. Not wanting to be left alone, the monkey follows him and boards the cargo ship. Ted returns home and finds advertisements for the shrine all over the city.

In Ted's apartment building, the monkey makes his way to the penthouse and vandalizes the walls of Ted's neighbor, Miss Plushbottom, with paint. Due to the building's strict no-pet policy, Ted is evicted by Ivan, the Russian doorman. At the museum, Ted reveals the idol's actual size to Mr. Bloomsberry and is kicked out by Junior after the monkey accidentally destroys an Apatosaurus skeleton. After a failed call to the animal control service, Ted and the monkey are forced to sleep outside in a park, where they start to bond. The next morning, Ted follows the monkey into the zoo, where Maggie and her students name the monkey George after a nearby statue of George Washington. George floats away on helium balloons that are popped by bird control spikes, but he is saved by Ted.

At the home of Clovis, an inventor, George discovers that an overhead projector makes the idol appear 40 feet tall. Ted shows the projector to Mr. Bloomsberry, who sees it as the only way to save the museum and tells Ted that he is proud of him. The still jealous Junior pours some of his coffee on the projector and gives the rest to George, blaming him when the projector breaks. With his plan derailed, Ted sadly informs the public that the museum will permanently close and that there is no idol. Ted has a falling-out with George and orders him to leave, allowing animal control to capture George to be returned to Africa.

Ted speaks with Maggie, who helps him understand what is important in life. He sneaks onto the ship and reunites with George in the cargo hold. George notices that the idol reveals a pictogram when turned to the light, and Ted realizes that it is a map leading to the real idol, which they find in the jungle.

The real idol is displayed in the museum, which reopens with new interactive exhibits. Although disappointed that he did not get his parking lot, Junior gets a job as a valet and finds joy in his father finally being proud of him. Ivan, who has grown fond of George, invites Ted to move back into his apartment. Ted and Maggie share a romantic moment, but are interrupted by George, who has activated a rocket ship; Ted jumps in and they repeatedly circumnavigate the globe.

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

Producers Jon Shapiro and David Kirschner contacted Margret Rey in 1990 about the possibility of producing a film based on the classic children's stories that she wrote with her husband, H. A. Rey. Shapiro recalled that he promised her to make the best version of Curious George as possible.[6] Rey agreed and Imagine Entertainment secured the film rights for Curious George in June 1990, with plans to produce a live action film jointly with Hanna-Barbera Productions.[13]

Universal Pictures acquired the merchandising rights to Curious George from publisher Houghton Mifflin in September 1997, after Margret Rey's death the previous year.[14][15] Larry Guterman signed on to direct in 1998 and worked closely with Imagine Entertainment co-chairman Ron Howard to develop the film.[16] However, Guterman left the project reportedly after budget concerns about the film's special effects led Universal and Imagine to postpone production.[17][18] By January 1999, the project continued to be "in active development".[6]

Universal and Imagine were in finalizing a deal with Brad Bird to write and direct a Curious George film that combined live action and computer-generated imagery (CGI) in October 1999,[18] but Bird left the project in 2000 when he was hired at Pixar.[19] In July 2001, the newly merged Vivendi Universal acquired Houghton Mifflin, with plans to make Curious George the company's new mascot, coincident with the film's development and release (Houghton Mifflin would be sold the following year due to Vivendi's mounting financial pressures).[20] Bird left the project after the studios decided to shift the film to all-CGI, and in December, Universal was in negotiations with David Silverman to direct the film.[21][22] By September 2003, Jun Falkenstein signed on to direct the screenplay,[23] but was later fired by the studio and replaced by Matthew O'Callaghan in August 2004.[6]

Writing[edit]

According to Stacey Snider, then-chairman of Universal Pictures, it was challenging to turn the relatively simple Curious George books into a full-length film with substantial character development.[6] During the film's production process, many screenwriters wrote potential scripts for the project, including Joe Stillman, Dan Gerson, Babaloo Mandel, Lowell Ganz, Mike Werb, Brian Levant, David Reynolds, and Audrey Wells.[8][6][18][24] Kirschner said that screenwriter Pat Proft wrote a live action draft of the film that contained a "funny stuff", but was also focusing on the relationship between The Man with the Yellow Hat and George the monkey, which was "really difficult to capture the innocence of that".[6] Brewster recalled that earlier versions of the script by Brad Bird and William Goldman were darker in tone and more adult.[6][25]

When O'Callaghan signed on to direct, replacing Falkenstein, he and screenwriter Ken Kaufman rewrote the story, saying that they took some elements from the existing story and created new characters, simplified the story elements, and came up with the story of the film. They expanded the role of The Man in the Yellow Hat and gave him a name, making the script more like a buddy film rather than one that was focused primarily on George.[8] The final script contained scenes inspired by many of the earlier books, including Curious George, Curious George Takes a Job, and Curious George Flies a Kite.[8][6]

Animation[edit]

When Imagine Entertainment obtained the rights to Curious George in 1990, a live action feature was planned; by 1999, Brad Bird was in talks to direct the film as a combination of live action and CG.[6] The success of Shrek in 2001 led Imagine co-chairman Brian Grazer to shift the film towards all-CG, saying at the time that George would be easy to convey in CGI animation rather than in live-action mix.[26] Eventually, a final decision was made to use traditional 2D animation for the film to recreate the look and feel of the Curious George books.[8][27] According to executive producer Ken Tsumura, CGI animation was used to create the environments for 20 percent of the film, including the city scenes, in order to allow objects to move in 3D space.[8]

A strict production schedule resulted in all animation work having to be completed within 18 months; Tsumura oversaw the outsourcing of the animation to studios around the world, including studios in the United States, Canada, France, Taiwan, and South Korea. The proportions of George and Ted were kept consistent with the books' illustrations, but their character designs were updated to accommodate the big screen, with O'Callaghan noting that they gave them eyes, pupils, teeth, etc. so Ted could enunciate dialog or to create strong expressions with George.[8] CG supervisor Thanh John Nguyen states that they tried to duplicate the look of the cars in the book, which Tsumura describes as bearing the look of the 1940s and 1950s; according to production designer Yarrow Cheney, the filmmakers also partnered with Volkswagen to design Clovis' red car that Ted drives, simplifying the design and rounding the edges.[28]

Reception[edit]

On the review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, Curious George has a 70% approval rating based on 107 reviews and an average rating of 6.10/10. The website's consensus reads: "Curious George is a bright, sweet, faithful adaptation of the beloved children's books".[41] On Metacritic, the film has an average score of 62 out of 100 based on reviews from 28 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[42] Audiences polled by CinemaScore during opening weekend gave the film an average grade of "A−" on an A+ to F scale.[43] Reviews frequently praised the film's light-hearted tone and its traditional animation style, though some criticized the plot and modern references.[41]

In The New York Times, Dana Stevens called the film "an unexpected delight", praising its "top-drawer voice talent" and "old-fashioned two-dimensional animation that echoes the simple colors and shapes of the books".[44] The Austin Chronicle's Marrit Ingman wrote positively of the film's "sweet, simple message" that "children see the world differently and have much to teach the people who love them".[45] Christy Lemire of the Associated Press praised George's character design, writing that "with his big eyes and bright smile and perpetually sunny disposition, he's pretty much impossible to resist".[46] Roger Ebert gave the film three out of four stars, noting that it remained "faithful to the spirit and innocence of the books" and writing that the visual style was "uncluttered, charming, and not so realistic that it undermines the fantasies on the screen". Ebert wrote that while he did not particularly enjoy the film himself, he nevertheless gave the film a "thumbs up" on his Ebert & Roeper show because he felt that it would be enjoyable for young children.[47]

Richard Roeper, Ebert's co-host, criticized the film for similar reasons and said that he could not "tell people my age, or someone twenty-five [years old], that they should spend nine or ten bucks to see this movie".[41] Brian Lowry of Variety felt that the plot was too simplistic, writing that the film consisted primarily of "various chases through the city" and was "rudimentary on every level".[48] On the other hand, Michael Phillips of the Chicago Tribune wrote that the film was "overplotted and misfocused" and that "the script's jokes are tougher to find than the shrine", though he praised the film for staying "relatively faithful to the style of the original and delightful H. A. Rey illustrations".[49] Jan Stuart of Newsday criticized the modern references in the film, including cell phones and lattes, writing that they resulted in "modernization traps that the makers of the very respectable Winnie the Pooh films managed to avoid".[41] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly also negatively noted the anachronisms in the film, such as the use of caller ID.[50]

The song "Upside Down" by Jack Johnson received a Satellite Award nomination for Best Original Song.[51]