Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period

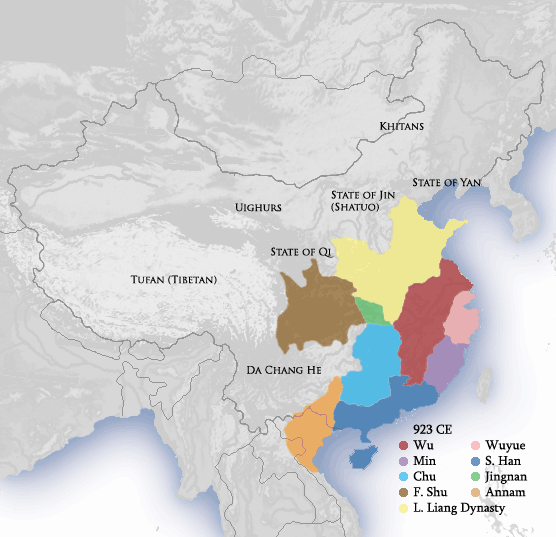

The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (Chinese: 五代十國) was an era of political upheaval and division in Imperial China from 907 to 979. Five dynastic states quickly succeeded one another in the Central Plain, and more than a dozen concurrent dynastic states, collectively known as the Ten Kingdoms, were established elsewhere, mainly in South China. It was a prolonged period of multiple political divisions in Chinese imperial history.[1]

Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms

五代十國

五代十国

Wǔ dài shí guó

Wǔ dài shí guó

Wu3 tai4 shih2 kuo2

Ng5 doi6 sap6 gwok3

Traditionally, the era is seen as beginning with the fall of the Tang dynasty in 907 and reaching its climax with the founding of the Song dynasty in 960. In the following 19 years, Song gradually subdued the remaining states in South China, but the Liao dynasty still remained in China's north (eventually succeeded by the Jin dynasty), and the Western Xia was eventually established in China's northwest.

Many states had been de facto independent long before 907 as the late Tang dynasty's control over its numerous fanzhen officials waned, but the key event was their recognition as sovereign by foreign powers. After the Tang collapsed, several warlords of the Central Plain crowned themselves emperor. During the 70-year period, there was near-constant warfare between the emerging kingdoms and the alliances they formed. All had the ultimate goal of controlling the Central Plain and establishing themselves as the Tang's successor.

The last of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms regimes was Northern Han, which held out until Song conquered it in 979. For the next several centuries, although the Song controlled much of South China, they coexisted alongside the Liao dynasty, Jin dynasty, and various other regimes in China's north, until finally all of them were unified under the Yuan dynasty.

Law[edit]

In later tradition, the Five Dynasties is viewed as a period of judicial abuse and excessive punishment. This view reflects both actual problems with the administration of justice and the bias of Confucian historians, who disapproved of the decentralization and militarization that characterized this period. While Tang procedure called for delaying executions until appeals were exhausted, this was not generally the case in the Five Dynasties.[19]

Other abuses included the use of severe torture. The Later Han was the most notorious dynasty in this regard. Suspects could be tortured to death with long knives and nails. The military officer in charge of security of the capital is said to have executed suspects without inquiry.[19]

The Tang code of 737 was the basic statutory law for this period, together supplemental edicts and collections.[19] The Later Liang promulgated a code in 909.[19] This code was blamed for delays in the administration of justice and said to be excessively harsh with respect to economic crimes. The Later Tang, Later Jin, and Later Zhou also produced recompilations. The Later Han was in power too briefly to make a mark on the legal system.[19]