Glass ceiling

A glass ceiling is a metaphor usually applied to people of marginalized genders, used to represent an invisible barrier that prevents an oppressed demographic from rising beyond a certain level in a hierarchy.[1] No matter how invisible the glass ceiling is expressed, it is actually an obstacle difficult to overcome.[2] The metaphor was first used by feminists in reference to barriers in the careers of high-achieving women.[3][4] It was coined by Marilyn Loden during a speech in 1978.[5][6][7][8]

This article is about a metaphor. For more information about the barrier that prevents minorities from reaching the upper rungs of the corporate ladder, see Gender pay gap.

In the United States, the concept is sometimes extended to refer to racial inequality.[3][9] Minority women in white-majority countries often find the most difficulty in "breaking the glass ceiling" because they lie at the intersection of two historically marginalized groups: women and people of color.[10] East Asian and East Asian American news outlets have coined the term "bamboo ceiling" to refer to the obstacles that all East Asian Americans face in advancing their careers.[11][12] Similarly, a multitude of barriers that refugees and asylum seekers face in their search for meaningful employment is referred to as the "canvas ceiling".[13]

Within the same concepts of the other terms surrounding the workplace, there are similar terms for restrictions and barriers concerning women and their roles within organizations and how they coincide with their maternal responsibilities. These "Invisible Barriers" function as metaphors to describe the extra circumstances that women go through, usually when they try to advance within areas of their careers and often while they try to advance within their lives outside their work spaces.[14]

"A glass ceiling" represents a blockade that prohibits women from advancing toward the top of a hierarchical corporation. These women are prevented from getting promoted, especially to the executive rankings within their corporation. In the last twenty years, the women who have become more involved and pertinent in industries and organizations have rarely been in the executive ranks.

History[edit]

In 1839, French feminist and author George Sand used a similar phrase, une voûte de cristal impénétrable, in a passage of Gabriel, a never-performed play: "I was a woman; for suddenly my wings collapsed, ether closed in around my head like an impenetrable crystal vault, and I fell...." [emphasis added]. The statement, a description of the heroine's dream of soaring with wings, has been interpreted as a feminine Icarus tale of a woman who attempts to ascend above her accepted role.[21]

Marilyn Loden invented the phrase glass ceiling during a 1978 speech.[5][6][7][8]

According to the April 3, 2015, The Wall Street Journal the term glass ceiling was notably used in 1979 by Maryanne Schriber and Katherine Lawrence at Hewlett-Packard. Lawrence outlined the concept at the National Press Club at the national meeting of the Women's Institute for the Freedom of the Press in Washington DC.[22] The ceiling was defined as discriminatory promotion patterns where the written promotional policy is non-discriminatory, but in practice denies promotion to qualified females.

The term was later used in March 1984 by Gay Bryant, who is credited with popularizing the glass ceiling concept.[23] She was the former editor of Working Woman magazine and was changing jobs to be the editor of Family Circle. In an Adweek article written by Nora Frenkel, Bryant was reported as saying, "Women have reached a certain point—I call it the glass ceiling. They're at the top of middle management and they're stopping and getting stuck. There isn't enough room for all those women at the top. Some are going into business for themselves. Others are going out and raising families."[24][25][26] Also in 1984, Bryant used the term in a chapter of the book The Working Woman Report: Succeeding in Business in the 1980s. In the same book, Basia Hellwig used the term in another chapter.[25]

In a widely cited article in the Wall Street Journal in March 1986 the term was used in the article's title: "The Glass Ceiling: Why Women Can't Seem to Break The Invisible Barrier That Blocks Them From the Top Jobs". The article was written by Carol Hymowitz and Timothy D. Schellhardt. Hymowitz and Schellhardt introduced glass ceiling was "not something that could be found in any corporate manual or even discussed at a business meeting; it was originally introduced as an invisible, covert, and unspoken phenomenon that existed to keep executive level leadership positions in the hands of Caucasian males."[27]

As the term "glass ceiling" became more common, the public responded with differing ideas and opinions. Some argued that the concept is a myth because women choose to stay home and showed less dedication to advance into executive positions.[27] As a result of continuing public debate, the US Labor Department's chief, Lynn Morley Martin, reported the results of a research project called "The Glass Ceiling Initiative", formed to investigate the low numbers of women and minorities in executive positions. This report defined the new term as "those artificial barriers based on attitudinal or organizational bias that prevent qualified individuals from advancing upward in their organization into management-level positions."[25][26]

In 1991, as a part of Title II of the Civil Right Act of 1991,[28] The United States Congress created the Glass Ceiling Commission. This 21 member Presidential Commission was chaired by Secretary of Labor Robert Reich,[28] and was created to study the "barriers to the advancement of minorities and women within corporate hierarchies[,] to issue a report on its findings and conclusions, and to make recommendations on ways to dis- mantle the glass ceiling."[1] The commission conducted extensive research including, surveys, public hearings and interviews, and released their findings in a report in 1995.[3] The report, "Good for Business", offered "tangible guidelines and solutions on how these barriers can be overcome and eliminated".[1] The goal of the commission was to provide recommendations on how to "shatter" the glass ceiling, specifically in the world of business. The report issued 12 recommendations on how to improve the workplace by increasing diversity in organizations and reducing discrimination through policy.[1][29][30]

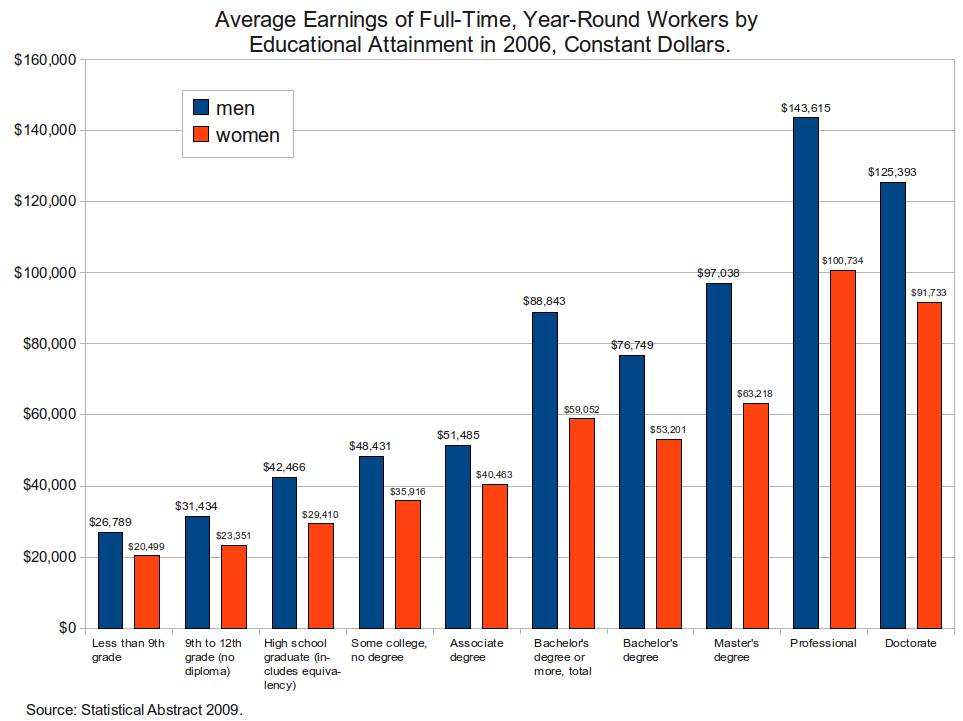

The number of women CEOs in the Fortune Lists has increased between 1998 and 2020,[31] despite women's labor force participation rate decreasing globally from 52.4% to 49.6% between 1995 and 2015. Only 19.2% of S&P 500 Board Seats were held by women in 2014, 80.2% of whom were considered white.[32]

Hiring practices[edit]

When women leave their current place of employment to start their own businesses, they tend to hire other women, and men to hire other men. These hiring practices (seemingly) diminish "the glass ceiling" effect because there is a perception of less competition of capabilities and sex discrimination. They appear to ally with the idea of "men's work" and "women's work".[40]

Cross-cultural context[edit]

Few women tend to reach positions in the upper echelon of society, and organizations are largely still almost exclusively led by men. Studies have shown that the glass ceiling still exists in varying levels in different nations and regions across the world.[41][42][43] The stereotypes of women as emotional and sensitive could be seen as key characteristics as to why women struggle to break the glass ceiling. It is clear that even though societies differ from one another by culture, beliefs, and norms, they hold similar expectations of women and their role in society. These female stereotypes are often reinforced in societies that have traditional expectations of women.[41] The stereotypes and perceptions of women are changing slowly across the world, which also reduces gender segregation in organizations.[44][42]