Historicity of the Bible

The historicity of the Bible is the question of the Bible's relationship to history—covering not just the Bible's acceptability as history but also the ability to understand the literary forms of biblical narrative.[1] One can extend biblical historicity to the evaluation of whether or not the Christian New Testament is an accurate record of the historical Jesus and of the Apostolic Age. This tends to vary depending upon the opinion of the scholar.

When studying the books of the Bible, scholars examine the historical context of passages, the importance ascribed to events by the authors, and the contrast between the descriptions of these events and other historical evidence. Being a collaborative work composed and redacted over the course of several centuries,[2] the historicity of the Bible is not consistent throughout the entirety of its contents.

According to theologian Thomas L. Thompson, a representative of the Copenhagen School, also known as "biblical minimalism", the archaeological record lends sparse and indirect evidence for the Old Testament's narratives as history.[3][4][5][6][7][8] Others, like archaeologist William G. Dever, felt that biblical archaeology has both confirmed and challenged the Old Testament stories.[9] While Dever has criticized the Copenhagen School for its more radical approach, he is far from being a biblical literalist, and thinks that the purpose of biblical archaeology is not to simply support or discredit the biblical narrative, but to be a field of study in its own right.[10][11]

Some scholars argue that the Bible is national history, with an "imaginative entertainment factor that proceeds from artistic expression" or a "midrash" on history.[12][13]

Materials and methods[edit]

Manuscripts and canons[edit]

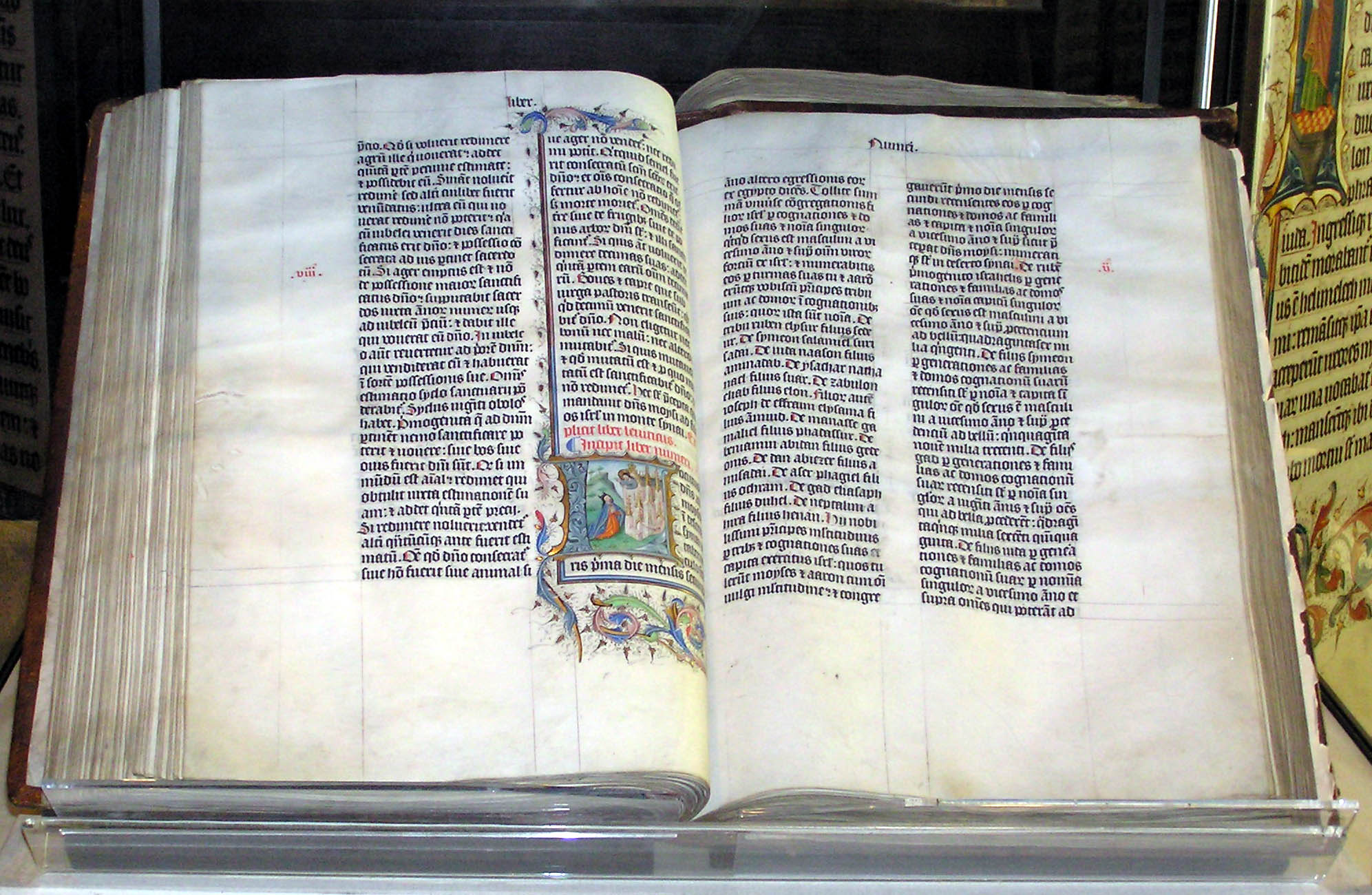

The Bible exists in multiple manuscripts, none of them an autograph, and multiple biblical canons, which do not completely agree on which books have sufficient authority to be included or their order. The early discussions about the exclusion or integration of various apocrypha involve an early idea about the historicity of the core.[14] The Ionian Enlightenment influenced early patrons like Justin Martyr and Tertullian—both saw the biblical texts as being different from (and having more historicity than) the myths of other religions. Augustine was aware of the difference between science and scripture and defended the historicity of the biblical texts, e.g., against claims of Faustus of Mileve.[15]

Historians hold that the Bible should not be treated differently from other historical (or literary) sources from the ancient world. One may compare doubts about the historicity of, for example, Herodotus; the consequence of these discussions is not that historians shall have to stop using ancient sources for historical reconstruction, but need to be aware of the problems involved when doing so.[16]

Very few texts survive directly from antiquity: most have been copied—some, many times. To determine the accuracy of a copied manuscript, textual critics examine the way the transcripts have passed through history to their extant forms. The higher the consistency of the earliest texts, the greater their textual reliability, and the less chance that the content has been changed over the years. Multiple copies may also be grouped into text types, with some types judged closer to the hypothetical original than others.